Published in Mada Masr

Italian translation in Internazionale

Between the static desert that “ceaselessly wears away” and the

perpetual sea that “furiously manifests renewal” is constituted

“my first vision of reality.”

These are the words of Alexandrian-born Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti. He wrote them in the Egypt of the 1930s. Today, a growing transnational community of thinkers has emerged in the shadow of the Arab uprisings, particularly the Egyptian revolution. This community exists between an ideologically devoid and austere Europe, and a politically merciless and radical Middle East. But who are they, and what is their “vision of reality”?

The Italians who traversed Egypt in recent years stand out, and are illustrative of this transnational community that exists today and whose ideas trump nationality and geopolitical relations.

The horrific death of Giulio Regeni, the Italian PhD student who was tortured and murdered while in Egypt doing academic research on trade unions, has perhaps mandated us to take a closer look at this intellectual community that produces knowledge against the backdrop of often tense historical, political and social relations across the Mediterranean.

“Rebellion was much needed in the Europe of austerity policies, and it [the act of rebellion] was happening in Egypt. Egypt was inspiring us to challenge [our reality],” Lucia Sorbera, an Italian feminist historian from Pisa who has researched Egypt for many years, told me.

Prior to the Arab uprisings in 2011, Italian activists’ interest in the Middle East was primarily focused on the Palestinian struggle. But after the uprisings, after Tahrir Square exported an invigorating theatrical protest that made many on the Italian peninsula turn their faces to the south, many Italian intellectuals became preoccupied with south Mediterranean countries, especially Egypt. Soon enough, the names of Egyptian revolutionaries, such as Alaa Abd El Fattah and Mina Daniel, were becoming known throughout Italian university campuses and activist communities.

This was quite a change from a year earlier. In 2010, the Egyptian state made a strange appearance in Italian affairs after former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi secured the release of his underage Moroccan mistress, “Ruby the Heart-stealer” (Karima al-Mahroug), by telling police she was then-President Hosni Mubarak’s niece.

After Regeni disappeared for seven days, only to be found tortured to death, the pro-state media struggled to justify the murder. There were half-hearted accusations of espionage, but they did not sell well — relatively harsher statements only came in response to the European Parliament resolutioncondemning Egypt. This might have been due to the fact that Regeni was Italian, and there was no handy history of interventionism that the state and its cronies could bank on to promote an espionage charge or propagandize their usual conspiracy theories. It is safe to say if Regeni were American or British, it would have been far easier to dig up that country’s history of interventionism in Egypt as implicit justification for his death. But for Italy, there was no strong case in this regard.

In terms of public perceptions, Italy does not invoke any immediate threat in the public imaginary. Pro-Italian sentiments are not uncommon — from elite writers who praise historic relations with Rome that date back to classic antiquity, to the street vendor who tries to sell you a dubious “da Itali!” (It’s Italian!) leather belt, to my plumber who markets me a clearly marked “Made in China” water pump as being originally from Italy. Italy is more often than not perceived as a trademark of class, elegance and relatable credibility. To many Egyptians, for one reason or another, Italians are familiar Europeans.

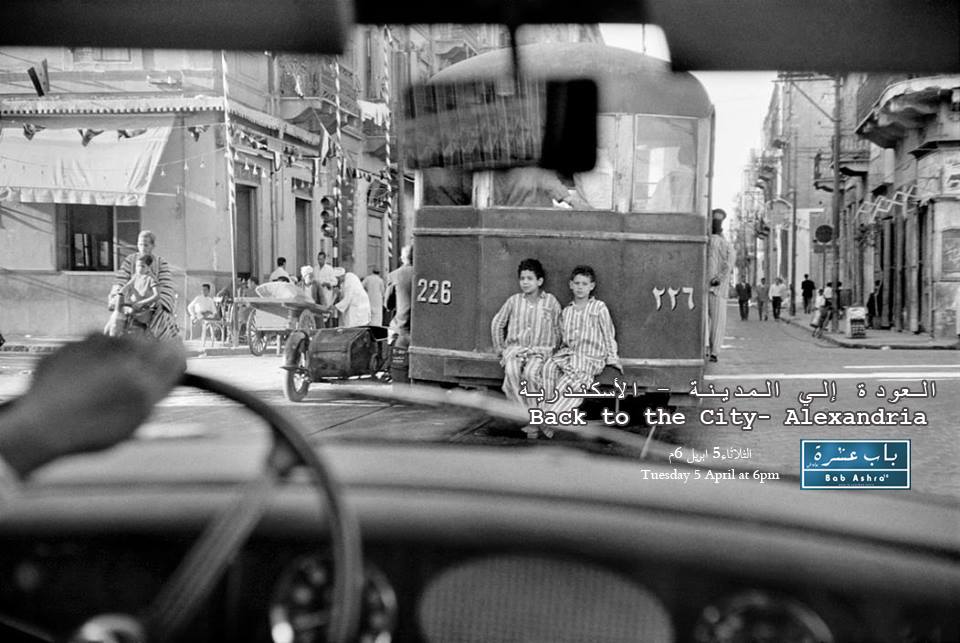

Italians fit well into Egypt’s current crippling nostalgia of our bygone neighbors — a cosmopolitan narrative of a “once-had-and-lost-modernity,” as social historian of modern Egypt Lucie Ryzova puts it. It is a narrative that the current pro-government elites use when they say that the president “will make Egypt great again.” It is also a narrative that is equally promoted by the nostalgic public (especially manifested in social media through sharing of black-and-white images of a “cosmopolitan” Egyptian imaginary) as condemnation of the regime for having failed to care for heritage and culture.

The narrative is reinforced daily by the faded grandeur of buildings that remind you of their Italian architects. Or the conversations of older-generation Egyptians from an urban center who would have at least warmly recollected one Italian friend growing up, before they disappeared in the trenches of Nasser’s nationalization policies. In short, there is a lurking pro-Italian sentiment that is invoked by their presence in a past imagined to be more glorious.

“I always felt that being Italian in Egypt gave me a huge advantage,” says Alessandro Accorsi, an Italian journalist from the Marche region. “It helped me deal with policemen, government, people in the street. Egyptians love Italians — there’s a sense of brotherhood between the two countries, and I think we are also perceived as ‘less threatening’ than other countries from a world politics/power perspective.”

While this is a sentiment expressed by Italians in Egypt, it was also subjected to manipulation by the state, which used statements like “but we love Italians” in a frail attempt to evade responsibility. Regeni’s murder undermined the relative safety Italians have long enjoyed in Egypt. No one is off-limits in an insecure security state.

Sorbera acknowledges that the distinct relationship is quite a popular notion. “We share many experiences in terms of popular culture, a patriarchal structure of society and the history of cultural production — let’s think about cinema, for example.” However, she cautions, especially in light of Regeni’s death, this is partly a mystification, as “Italy and Egypt occupy two different positions in the geopolitical Mediterranean and global system, and Italy is certainly not a police state in which hundreds of people are disappearing.”

Other Italians do not necessarily view the situation through this lens, and echo statements one also hears from some French and Greeks. One tells me, “While authoritarian neoliberal control through violence and torture takes place in Egypt, in Italy it happens through deprivation of basic rights.” Egypt’s unabashed violence and lax rule of law cannot be compared to Italy’s, but there is a unique experience Italians seem to undergo that can act as a powerful catalyst for them to move to and emotionally invest in Egypt.

The issue has, in part, to do with a number of faceless and predatory Italian corporations that have a stake in North Africa, especially Egypt. When the chief of Confindustria (Italy’s national chamber of commerce) stated a few years ago that the southern Mediterranean is our China and should be considered as our main market and commercial partners, his statements raised concerns and masked a darker narrative. As Omar Robert Hamilton has argued, Italy is implicated in Egypt’s violence: from Italian company Iveco, which exports police trucks that ran over Egyptian protestors, to weapons company Fiocchi, which contributed the bullets that ended the lives of countless peaceful protestors. This is just a small part of the story of Italian companies invested in Egypt’s economy of violence — the very system that enabled Regeni’s death.

However, Italian activists, journalists and academics are, in fact, extremely critical of this neoliberal global order. Their support for Egyptian struggles for justice is an extension of a deeply anti-Italian establishment position.

“In some ways, [Egyptian president] Sisi and [Italian Prime Minister] Matteo Renzi are not any different,” says Azzurra Sarnataro, a researcher from Naples who works on community development in Cairo’s informal areas. “I stand against Sisi in the same way I stand against Renzi and his political and economic policies.”

By understanding this line of thinking — commonly expressed in different words — it becomes clear that Italians in Egypt are partly projecting their anti-neoliberal grievances onto Egypt.

“Egypt has always been (and still is) an excellent laboratory where it was possible to observe the interplay of endogenous and exogenous factors, and their impact on politics and society … the setup of power games on an ideological and religious basis, and the exposure of conflict of interests and the corruption machine,” says Chiara Diana, a researcher from the Campania region who writes on the post-revolution’s political socialization of Egyptian children.

Accorsi notes that he felt the Egyptian struggle was his struggle: “Egypt gave me an ideological space that I couldn’t find in Italy, exactly because the [Egyptian] revolution happened at a time when Italian social movements were living a general crisis and political apathy was reigning sovereign.”

Sorbera offers a more tempered view, saying, “Being away from home always provides a different — and I would say productive — space to articulate a more nuanced awareness of oneself and others.”

On the other hand, expanding on Accorsi’s view, Diana argues, “I think there is currently an ideological and political flattening in Italy that monopolizes citizens’ attention on issues such as security, terrorism, protection of national territory and culture. This prevents them from addressing problems related to their daily struggles, like the economic crisis or budget cuts in social welfare and education. In this way, there is the potential risk that those fundamental struggles take a back seat, while discrimination, fear, self-sufficiency and nationalisms lead the field.”

This, she states, is where Egypt breaks the morbid status quo. “In Egypt, the subalterns’ demands for human rights, social justice and freedom allow people like me to continue to believe in the dignity of human beings and in the struggle for their rights.”

While it might not be unusual to find such views in other Western nationals, the Italians stand out due to the more historically, socially and geographically intimate approaches they take toward the Mediterranean and Egypt, which can be summed up by what an Italian professor at the University of Bologna told his class: “The issue is not whether Turkey or Israel should join the European Union, but whether Italy should join the Arab League.”

Italy is also witnessing growing anti-Arab and anti-Muslim xenophobia, tied especially to the refugee crisis. But it’s not the bigots who are choosing to head south — those who follow an idealized line of thought from the peninsula’s base are crossing the sea because of such a perceived affinity.

“Many of us believe in the Mediterranean Sea, both as a space of historical and cultural bonds and a privileged space to express dissent,” says Enrico De Angelis, a scholar on media studies from Naples. “Italians complete their collective identity with the southern coast of the Mediterranean, and look to the south as they look to the north.”

“I feel a human proximity with Egyptians concerning some fundamental struggles, such as dignity of life, social justice and guaranteeing of basic human rights. Why this proximity? I don’t know, maybe because I come from the south of Italy, where social conditions are sometimes hard, like in Egypt,” Diana says. Sarnataro is more adamant, saying, “We as southern Italian, even those among us who are not politicized, share with Egypt an understanding of economic difficulties.”

Yet De Angelis takes exception toward such a widely held view, and states, “This can be a distortion due to the fact that we have regular access to some parts of Egyptian society and not all of it. There is a big difference between Italy and Egypt economically. Maybe you can say that the struggles against neoliberal policies can be the same, but from different positions.”

Nonetheless, what emerges across the board is a distinct southern Italian identity harnessed to building a bridge to North Africa. This is further legitimized by the fusion of the North’s anti-southern discrimination and anti-Arab racism, which was conveyed to me by an Italian professor from the University of Cà Foscari Venice, through the use of a 1960s Italian joke: Sicily is the only peaceful Arab country, as it has not yet declared war on Israel.

This is not to suggest that Regeni is a product of all the aforementioned factors. In fact, he left Italy at the age of 17 — a decade before he was murdered. Nevertheless, he was plugged into the Egyptian public sphere as an “Italian,” which came with the semiotics and social signifiers understood by the political, cultural, social and historical Egyptian matrix. Regeni’s gregarious personality, dynamic work and humane ideals — all within a “pro-Italian” environment — may have helped him until the illusion of immunity was shattered. It has “made us all equal in fear,” says Francesca Biancani from Bologna, a scholar on Middle East history with a focus on colonial Egypt.

Given their long and intimate experience with Italian activists and socialists over the years, it was not surprising that Egyptian revolutionaries circulated the hashtag, “Giulio is one of us and died like one of us.” Just as Rachel Corrie was adopted by the Palestinian cause, Regeni is possibly the first non-Egyptian to be inducted into the Egyptian revolution’s narrative of martyrdom. This was the first attempt to challenge the equation of citizenship and loyalty. That a member of a transnational community can also exhibit an equal, if not stronger, loyalty to Egypt’s public welfare is telling.

Regeni’s death, as Biancani notes, “could also be a promising new start for a wider struggle, really linking young generations with the same sensibility on both shores, as it seems to me that the way those in power are going back to utilizing very coercive forms of domination — almost anachronistically — is happening everywhere with varying degrees.”

The autobiographical novel by Italian writer Fausta Cialente, Le quattro ragazze Wieselberger (The Four Wieselberger Girls), is perhaps telling of the vision of Italians preoccupied by Egypt today. In 1922, Cialente witnessed a fascist parade underway from Milan to Rome. She responded by wanting to go back home to Alexandria in a “Middle East, all open, where freedom for us Europeans was full and pleasant.” She would later move to Cairo to air anti-Mussolini and anti-fascist propaganda over the radio.

The Italians who are preoccupied with Egypt today possibly see elements of Italy’s fascist past in the present world of Cairo and Alexandria — the cities that once offered them political safety and tolerance are now increasingly exhibiting the fascist tendencies ominously narrated by their grandparents. The road linking the two cities became the transitional cemetery to Regeni’s body when it was found dumped on the Cairo-Alexandria highway.

For Regeni, it seems to me that it was never just about writing a dissertation — tumultuous Egypt was the place where, as a student, his political identity could flourish through imaginative ways it could not back in Italy. It is where his “vision of reality” could be enriched and fulfilled. Like many of Italy’s youth who see their upward mobility hampered by nepotism, Regeni could, at the very least, “develop his sense of being a global citizen,” as Italian journalist Paola Caridi writes on her Invisible Arabs blog.

Maybe no one could better express Regeni’s vision more profoundly than his mother, Paola Regeni: Giulio was “an Italian citizen, a citizen of the world who could have helped many people in Egypt and the Middle East. He had foresight, that’s why he learned Arabic and was so interested in economics … [and] marginalization … He did not go to war. He was not a journalist. He was not a spy. He was a contemporary young man of the future who was studying. He went for research, and he died under torture.”

What response can be given when Regeni came to Egypt full of idealism and selflessness to understand the poor and downtrodden, only to tragically meet a fate not unknown to them?

I cannot think of a sentence that captures the monumental moral crisis that Egypt is faced with like this one by Regeni’s mother: “On his face, I saw all the world’s evil poured on him.”

Paola Regeni spoke from the other side of the sea. She held up a mirror toward Egypt and said, “What is happening now should make us all think about it. We lost Giulio, but many others ended up the same way as Giulio. So he might be an ‘isolated case’ for Italian history, but not if we look at Egypt and other countries.”

The mother of Khaled Saeed — the 28-year-old Alexandrian whose death under police custody in 2010 helped incite the Egyptian revolution — responded in kind. “I want to thank you for standing with us, and that you care about torture cases in Egypt,” she said.

In a coffee shop across the Alexandrian Corniche, a man asked why Italy is still making a fuss about Regeni. A patron stood up in the corner and yelled, “Because that’s what it looks like when a country actually cares for its own citizens.” An eerie silence followed. An evocative reminder why, some 50 meters away from the same coffee shop, Khaled Saeed was killed by two police officers almost six years ago, and his death mattered then — surely mattered enough for a revolution to be sparked. The same revolution’s fifth anniversary that saw Regeni go missing.

In the same anti-fascist spirit that Cialente wrote about in the 1920s, Regeni was, in a sense, a witness and warning siren, a harbinger of the rise of unaccountable rulers and the erosion of freedom, rights and human dignity. For that reason, among many, Regeni’s coming to Egypt was never in vain, and neither was his final departure.

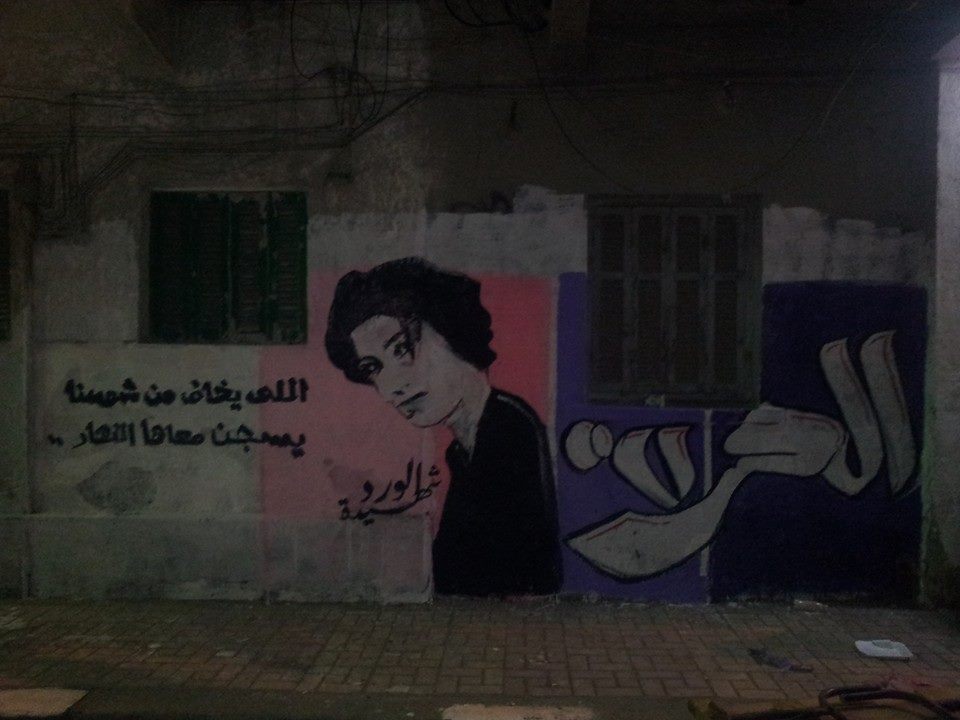

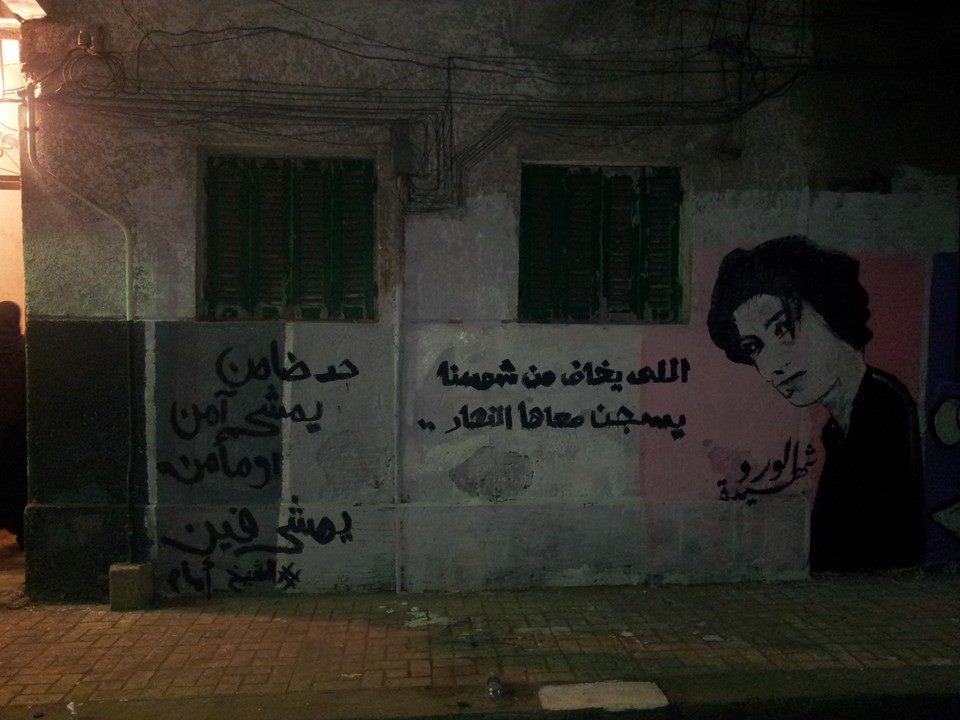

![[From Alexandria’s Stanley neighborhood: “The People,” the eternal cry of the revolutionary voice that would follow it up with “Demand the fall of [insert your current oppressor here].”](https://amroali.com/aspire/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/the-people-300x225.jpg)

!["The flower of Shaimaa" [in the form of a clinched fist]](https://amroali.com/aspire/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Shaimaa-el-Sabbagh-5.jpg)