This short essay originally appeared in the Madrid–based Fundacion Alternativas.

The modern history and contemporary nature of Alexandria is a brew of different identities that give off (or once gave) a distinct resonance: Mediterranean, Egyptian, Arab, African, Middle Eastern, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Levantine, among others. But the one profile that emerges as rooted in Alexandria’s existential survival is the Mediterranean identity. Within a few decades, rising sea levels will inundate parts of Alexandria in what could be the start of history’s closing curtains on the 2300-year-old city. Along with political and institutional will, it is imperative that Alexandria’s relationship to the Mediterranean shifts its face from past and present towards the future and pushed further into a wider regional narrative.

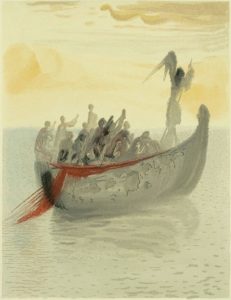

Ask an Alexandrian what makes up their identity and the first word you will most likely hear is the sea. The sea is central to the popular imagination, literature, films, theatre, escapism, growing up, families, wedding shoots, and a street art that reflects the bond with the sea and its history and myths: mermaids, citadel, centurions, Alexander the Great, and lots of ship-themed graffiti. Right down to the common line “If I leave Alexandria, I will feel like a fish out of water.”

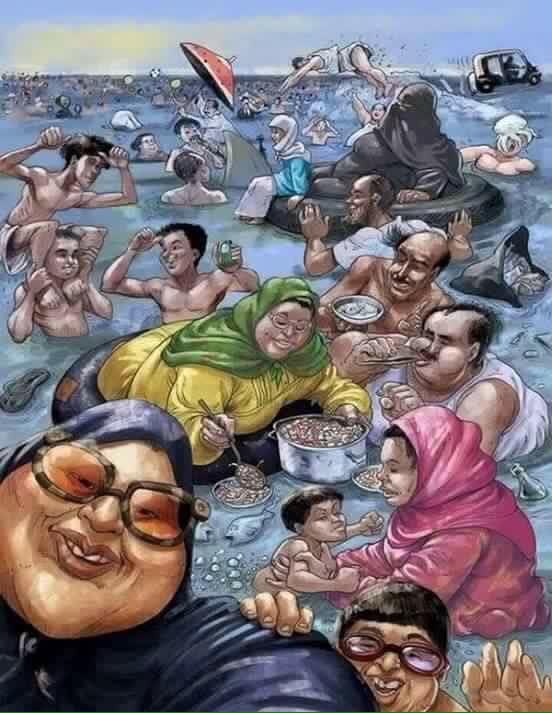

The long stretch of corniche and wave breakers have displaced the beaches as the dividing line, liminal space, and intersection between the public and the sea. Access to the corniche and the ability to see the sea is a continuing battle in light of the privatisation and “development” drive that has, in many cases, cut off the public from viewing the sea, let alone accessing it. Yet pockets of communal respite are to be found. At the outset of the pandemic, the corniche furnished many of Alexandria’s young with the newly discovered hobby of kite flying that became a unifying public spectacle as even street children could get access to cheaply made kites. I had never seen that high degree of elation induced by any activity before on the corniche in many years. Barely a month or so passed and the kites were banned by the government on the official reason that they were behind a series of accidents (which is a legitimate concern but outright banning is different to regulating). The kite had, for a moment, become a hovering icon that connected sky, sea, corniche, and public.

To speak of Alexandria in a regional narrative is nothing new. Since the 1990s, elite efforts have been made to reintegrate Alexandria into the Mediterranean imaginary – albeit a neoliberal one that succeeded its colonial predecessor. The government rehabilitated the façade of the city as several institutes directed energies to crystalizing Alexandria’s role in the Mediterranean world which included the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Anna Lindh Foundation, and the former Swedish Institute, along with various cultural centres and initiatives.

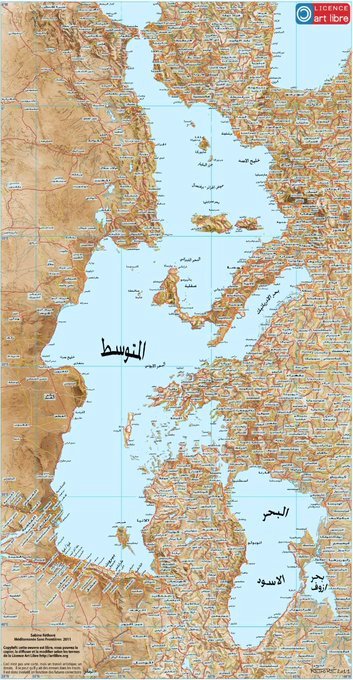

Yet an endeavor needs to expand the notion of the sea from one linked to the past that evokes nostalgia and childhood memories, as well as the present that touches upon romance, enchantment, leisure, and livelihoods, to a future where an apocalypse looms on the horizon. Not to terrify the populace, but rather to deepen civic responsibility – from anti-littering to reconsideration of investment decisions – as part of the fight against climate change that can complement the respective policy on the matter. As well as linking Alexandria to efforts made by other cities in the basin as part of an unfolding story that aims to rescue the historical hubs of the middle sea. However, short of radical adaption measures, it is Alexandria, the only major city in the Mediterranean, that is at the highest risk of being largely submerged by 2050. It is no wonder why popular Google searches for Alexandria in the context of climate change reveal bizarre questions such as “Does Alexandria Egypt still exist?” and “who destroyed Alexandria Egypt?” It is an omen the city can do without.

Time and again, events have shown that Alexandrian public engagement or interest, particularly among the young and students, in their city’s welfare is heightened when they feel the city is part of a regional or global story – whether it be visits by foreign heads of state, clean up campaigns, artistic troupes, or the Africa Cup. It is part of the conscious Alexandrian mode of living to make sense of the fractured present while living in the shadow of multiple ancestral giants. It is the “nature of identity”, individual or city identity no less, “to change depending on time, place, [and] audience.” In this case, the repositioning of Alexandria’s Mediterranean identity can no longer be limited to culture wars, Euro-centric elites, and postcolonial critiques. It is now a question of survival.

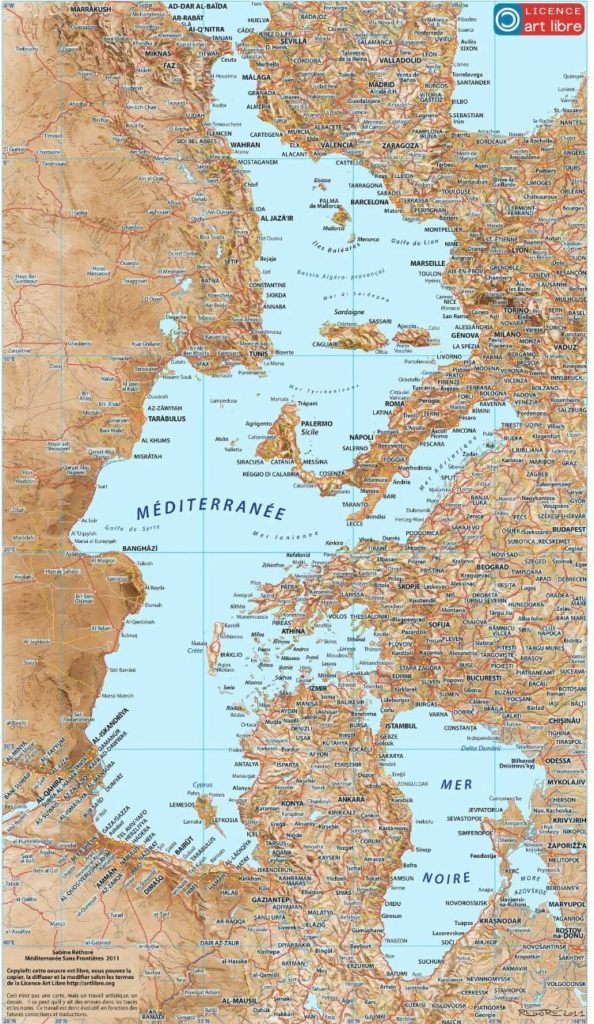

As I have argued before, the Mediterranean is a laboratory with natural demarcations, rich history, trade, and cultural ties that could enable “an overarching new Mediterranean narrative to be written through a series of conferences, symposiums, workshops and accessible publications” with the possibility of contributing to “animating forms of transnational citizenship, a project that builds a Mediterranean platform” that can construct a new narrative and social contract.

Alexandria needs to feel part of the neighborhood story and brought into a mission in which its fate is tied with the same menace confronting Beirut, Tunis, Tangiers, Barcelona, Marseilles, and the rest of the cities dotted around the basin. While many Mediterranean cities will suffer from rising sea levels to hotter temperatures, the menace is eyeing Alexandria with the utmost ferocity and has earmarked a swathe of the city to be turned into one large underwater museum. A rising sea level that will perhaps regurgitate onto the city’s future and permanently flooded streets the thousands of abandoned facemasks and lost kites.