I’m giving a talk (in Arabic) on 22 May 2019 at Human and the City for Social Research that explores Alexandria’s loss of public beaches and public spaces.

Click here for the Facebook event.

“Our inheritance was left to us by no testament” – René Char

“Alexandria has evoked both place and displacement, both achievement and frustration and a continuing search.” – Anthony Hirst & Michael Silk, Alexandria, Real and Imagined (2004)

Articles, posts, lectures, and videos, that deal with Alexandria-related issues or employs Alexandria as an illustration.

I’m giving a talk (in Arabic) on 22 May 2019 at Human and the City for Social Research that explores Alexandria’s loss of public beaches and public spaces.

Click here for the Facebook event.

This lecture will trace the historical and contemporary forces that shape the idea of civic joy and belonging in Alexandria, and its unravelling in recent decades under the weight of centralization, an illegal building craze, brain drain, consumerism, privatization, the slow vanishing common narrative, and, above all, the disintegration of the public space. The seminar will also explore the characteristics and implications of a peculiar despair across a growing swathe of the Alexandrian citizenry that is manifesting itself through a shared agony that glances around for answers, sensing that time is slowing down again, desiring to live in the past, and developing an obsession with any object that represents loss.

Click here for the Facebook event.

Click here for the Facebook event.

Published in Mada Masr, republished in openDemocracy, and Internazionale (Italian print edition)

“Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero,” Andrea cries in the 1938 play, Life of Galileo, by German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, to which Galileo responds: “No, unhappy is the land that needs a hero.”

Egypt can be that unhappy land, a land where farewell parties have outstripped homecoming parties. Where a young female doctor laments she wants to leave because “to give birth to a baby here feels morally wrong, it feels sort of illegal.” Where a juice seller sarcastically quips, “We no longer have time to think of anything else but survival, we don’t even have time to contemplate suicide.” When a country is mired in endless social and economic problems, and smothered in despair, the yearning grows for that batal (hero), that one human figure where all painful and complex abstracts will be realised within and resolved without.

Something happened in Egypt that short-circuited a sport that is often treated by governments of all persuasions as a distracting bread and circus for the masses. Something interrupted the despotic drive to stamp out the uniqueness from the flow of Egyptian life.

Enter Mohamed Salah armed with a moral code.

While Salah is seen to bring hope to many, he is an unsettling spectre that silently haunts the establishment, for he has options, international prestige and the perception of untouchability. He has grown to be more than a hero of football success. Salah is a different sort of hero, he is a hero of disruption, and a living paradox of a political voice without talking politics. Salah operates in a politics of juxtaposition in which his perceived immaculate persona is unconsciously contrasted with the familiar polluted forces of high politics.

While many of Egypt’s prominent and established figures seem to have an answer for everything, Salah shows up and we’re faced with difficult questions. Namely, why are we investing so much hope in one man? This is more than about the World Cup.

Salah is not a substitute for viable high politics. He is, after all, a football player, and a very good one at that, but his insertion into the volatile Egyptian climate sheds some light on what has gone wrong and why the current fervor around him can illuminate the question of Egyptian unhappiness.

Salah’s stance to steer away from politics, or from inadvertently disclosing his political leanings, has given him an amplified united base. Since the 2011 revolution, Egyptians have had to live with binaries: revolutionary versus counter-revolutionary, secular versus Islamist, civilian versus military, liberal versus hyper-nationalist, pro and anti-Brotherhood, among others. While many of these binaries have diminished under the shadow of the generals, the unity that has come in its place is a negative unity. It is almost always against something, such as terrorism, and when it stands for something, let’s say Egypt, it’s a nationalist straightjacket that is imposed, with no room for plurality of thought or voices.

Salah might just be the first figure in a while behind which pro- and anti-regime supporters can unite. In the words of an Egyptian doctoral candidate studying in California, “Salah is the reason I’m mending my relationship with Egypt.”

It has become commonplace to argue that unhappiness in Egypt is caused by high unemployment, poverty, dysfunctional education, censorship, a crackdown on independent voices, and overall human rights abuses. While there is no doubt these factors contribute to the misery of many Egyptians, there is something worse and pathological that lurks behind them all: The grim reality that new possibilities no longer emerge on the horizon. The dilution of hope that once offered the promise that unhappiness was a temporary moment, now feels for many like the ink of sadness has dried. Depression disarms you before repression even has time to put on its uniform.

For this reason, Salah is like a sudden assertion of human values within a dehumanising system. This did not arise when Salah helped defeat Congo, propelling Egypt into the World Cup last October. Astonishing football talent is not always enough to convert non-football watchers. Nor did his story of humble beginnings to stardom take hold in this moment. There was nothing original in any of these individual success stories. Perhaps because they remained just that: individual.

But then came the other, and equally decisive, side of Salah. Barely two weeks after this victory, and because of it, Salah was offered a luxury villa by entrepreneur Mamdouh Abbas. He politely declined the gift and suggested that a donation to his village Nagrig in Gharbia would make him happier. This move, along with many of his charitable acts, for non-football fans, including myself, was thunderous to say the least, and swayed us to his camp.

To put the implications of this act in a wider context: Cairo’s highways are nauseatingly choked with billboards flaunting the latest exuberant luxury real estate and gated compounds. It is an assault on the senses of millions of Egyptians who are puzzled as to how such developments take place in an era of painful austerity measures, in which they are being asked to continually sacrifice. The billboards, almost always in English and at times with white, blue-eyed European faces, loudly proclaim, “It’s time to think about you,” and, “This time it’s personal.” It is not enough that Egypt’s capitalism on crack and real estate speculation is skewing the economy, but it also ramps up hyper-individualism, greed, and various strands of self-hatred.

Salah’s rejection of the villa was a violent piercing into a culture of the grotesque and excessive, and signified his upholding of the values born, or crystallized, during the 2011 revolution that put the common good above all. His refusal was a significant breach in the business-as-usual patronage and wheeling and dealing circles. If Salah was loved for his victory over Congo, he was now respected more for this move and the many charitable stories that emerged, making it obvious that this has been his character for a long time, and that he didn’t reinvent himself for PR purposes. Love and respect are two different beasts. Egyptians have long missed looking up to someone who commands respect, at least someone who is not in exile, in prison, or long dead.

In recent years, Egyptians have had to live with the exhausting spectacle of doublespeak in which official interpretations are often in conflict with lived realities and common sense. The train heading to Alexandria is declared to be on its way to Aswan, as veteran journalist Yosri Fouda once put it. This war of attrition on rationality has plunged Egyptians deep into a spiral of conformity, scepticism and indifference toward each other. The idea of the higher good receded as officialdom continued, in Czech philosopher Václav Havel’s words, “not to excite people with the truth, but to reassure them with lies.” The intervention of Salah did not necessarily change all that, nor did it reverse the Orwellian trend, but he did help restore meaning to terms that had become scrambled: dignity became dignity again, principles became principles, kindness became kindness, and happiness became happiness.

Salah touched on another existential question within Egyptian state and society: the strong desire for international recognition. This phenomenon weaves its way through Egypt’s modern history. There have been concerted efforts to export Sisi’s branded Egypt, for example, with the new Suez Canal project billboards dotting New York’s Times Square with the slogan “Egypt’s gift to the world.” Salah, instead, lived up to fulfilling that slogan in a much more dramatic and compelling way. In fact, Salah has arguably had more impact on the world’s positive views of Egypt than all the recent years of tourist campaigns, international conferences and mega projects combined. In light of this, mentioning Salah in conversation can give many Egyptians a feeling of breathlessness, tingling hands and a sensation of weightlessness.

This in part has to do with the function of happiness and meaning. If the regime is not suffering from cherophobia (fear of happiness), it believes it can commodify happiness by stating it intends to make “Egyptians among the world’s happiest,” or through the recent discussions with the UAE’s Ministry of Happiness to “export” some of their cool psychedelic juice to Egypt.

Happiness is a question that spans a history of philosophical musings, from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, to Al-Ghazali’s Alchemy of Happiness, to Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols and the Antichrist. All of them would shun the Anglo-inspired utilitarianism of John Stuart Mills that speaks of happiness as the ultimate net objective and has been largely repackaged for neoliberal modernity, rather than a meaningful higher life that produces happiness as a by-product. In other words, you cannot separate the attainment of happiness from respect for justice, dignity, honour, etc. It doesn’t seem to phase the authorities that happiness is meaningless without rescuing vibrant citizenship, opening public spaces, providing fair trials, encouraging pluralism, and preventing overall existential meaning from being fragmented.

Salah offers glimpses into the voids spawned by the above fractures as he communicates not only on the instrumental level of football success, but with meaningful and empathic qualities that come with an honourable character. It is no wonder that Salah was able to inspire calls to a drug user helpline to shoot up by 400 percent.

Salah’s fame, coupled with his stance on religion, comes interestingly at a time when many Egyptians are renegotiating their faith, identity markers and boundaries. The norms of what once constituted a religious person are breaking down under the weight of the country’s endless contradictions. All this takes place beneath the purview of a state that uses religion to arbitrarily police the public space, and preachers who continue to push a baroque Islam at the expense of the religion’s humble essence.

The rise of a widespread spiritual passivity contrasts with Salah’s faith, which has come to animate his public life. He saw no need to dismiss or distil his Muslim identity, even after he achieved a turbo-charged social mobility and stardom. This is not lost on many. The sight of Salah’s veiled wife, Maggie, by his side on a green oval in a European city before the eyes of millions, is a hypnotic sight to Egyptians (and the rest of the world) precisely because it is unusual, particularly at a time of heightened anxieties toward Muslims in the West. “I respect him as he is not embarrassed nor does he try to hide his veiled wife after all that success,” an Alexandrian barber says.

It is for the same reasons that Salah can sprout pan-Arab and pan-Islamic wings across the Arab and Muslim world. He has made it into Lebanon’s graffiti scene and protest ballots in the Lebanese elections (just like Egypt) to a bizarre planned peaceful protest outside the Spanish embassy in Jakarta after the injurious tackle by Sergio Ramos. The Arab world’s traditional idea of a leading, strong, vibrant, noble and outward-looking Egypt – one that spearheads the arts, preserves the seat of intellectual Sunnism, champions pan-Arabism, and stands up for the Palestinian cause – is projected onto Salah with deafening force. Between prostrating on the grass and raising his index fingers to the heavens, hundreds of millions of Muslims are drawn to this well-understood language of piety.

But this attraction transcends culture and religion. As the western world is bogged down in neoliberal sterility, rampant consumerism, loneliness, high-level scandals, populism, xenophobia against refugees and immigrants, anti-Muslim bigotry, anti-Semitism and fake news, the multi-layered Salah – the intimately relatable footballer and loving father who kicks a ball with his daughter Makka – stands out like a moment of truth and living universality, with a mammoth mural recently going up in Times Square reflecting his larger than life image.

Albert Camus wrote to an estranged German friend in 1943: “I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice. I don’t want any greatness for it, particularly a greatness born of blood and falsehood. I want to keep it alive by keeping justice alive.”

Salah perhaps embodies this ideal. That love of country does not require drums and chest-beating, but grace, sincerity, modesty and charity. He is a reminder to Egyptians that there exists a better human nature in a landscape barren of prominent reverential role-models. To Egypt and even the rest of the world, Salah is the outlier that proclaims the alternative to nationalism is not treachery but civic responsibility, the alternative to stifling religious conservatism does not always have to be apathy or mockery of the sacred, but breathing faith into a sound value system, and the alternative to injustice can be forgiveness. Ultimately, people had almost forgotten what humility among those with renown looks like. Particularly, a humility that is relentless and consistent, despite being trialled under the stadium floodlights and the stars sprinkled across the Liverpool night sky.

Salah is the rare homecoming party Egyptians have long awaited. His face on dangling lanterns lights up dark alleyways, and his colourful posters germinate over the debris of fading election posters in a country that sees official and media-manufactured heroes reckon with publicly-anointed heroes.

While it cannot be implied nor expected that Salah could impact the political situation in Egypt, his animated existence spotlights entry points back into the realm of authenticity. He widens the moral imagination of an attentive public and parades the possibilities that infer that the rhythm of life involves more than birth, marriage, death and even sports. He also raises questions that many power-holders will have to grapple with eventually, someday: That, above all, there are reasons why people ache for heroes in the first place. — What have you done to make them this unhappy?

Understanding Alexandria as a second city can shed light on how historical imaginaries influence present-day experiences, as well as the cultural practices and social norms that arise; as the very notion of “second,” and the inevitable comparisons with other cities that it spurs, can drive decisions and shape a peculiar approach to one’s city.

Understanding Alexandria as a second city can shed light on how historical imaginaries influence present-day experiences, as well as the cultural practices and social norms that arise; as the very notion of “second,” and the inevitable comparisons with other cities that it spurs, can drive decisions and shape a peculiar approach to one’s city.

Time: 7pm

Date: Sunday 22 April 2018

Venue: Institut français d’Egypte à Alexandrie

Click here for the Facebook event.

The philosophy talk and conversation will examine the forces behind the degrading of aesthetics and the normalization of mediocrity in everyday life.

This event is not so much about urban studies and public space as it is about delving into the toxins of modernity and its relationship to the human condition under assault. It will explore themes of shapelessness, powerlessness, meaninglessness, responsibility, alienation and asks, above all, what is ugly? Questions will be raised to help absorb the nature of the problem, and how do people refuse this malaise? The session will introduce concepts from the writings of Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd, Edmund Burke, Friedrich Nietzsche, Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, and Václav Havel.

The event will primarily be in English, however, an Arabic session will be followed up in the next month.

Venue: French Cultural Institute Alexandria (L’institut Francais D’Egypte A Alexandrie)

Date: 7 October 2017

Time: 7.30pm

Facebook page

Published in Mada Masr. (Click here for the Arabic translation). Republished in the Asia Times.

Published in Mada Masr. (Click here for the Arabic translation). Republished in the Asia Times.

I have grown accustomed to gradually seeing religious festivities being disemboweled of their meaning, whether it’s the entertainment-saturated Ramadan, or the hyper-commercialized Christmas. But the Islamic Eid al-Adha (Feast of the Sacrifice) stands out starkly, as it has been built on an all-encompassing annual spectacle, with the blood of sheep and cattle running through the veins of Egyptian cities. To live in a part of Alexandria surrounded by butchers, as I do, is to be unfortunately placed at one of the city’s aorta.

Eid al-Adha, which celebrates the Prophet Abraham’s sacrifice, is rich in meaning and symbolism, from the perseverance of the human condition to the traditional binding of families and community, as well as allowing, at the very least, a metaphorical reaching out to Jews and Christians who can relate to the tribulations of Abraham. More so, given that many poor Egyptians are “vegetarian” by default, as they can rarely afford meat, Eid is an opportunity to put meat on their tables. This is not to mention the money and other charitable gifts that are given out generously on this festive occasion.

When it comes to charity, Eid Al-Adha is an exemplar. When it comes to the actual sacrifice, it has become frighteningly lacking.

Egyptian society over the years has developed an unhealthy obsession with ostentatious displays of piety. Eid al-Adha has regressed to the point where public piety meets peak voyeurism, leading to the collapse of any semblance of a public sphere. The origins of this problem came with urbanization that saw the ritual move from farms and slaughterhouses to the streets. And for a long time, the practice was undertaken in the building’s manwar (interior) by a few families. Now, driven by the flaunting of wealth, it has reached an industrial scale, with minimal supervision, regulation or consensus. The authorities, despite being against it and issuing fines here and there, would rather react swiftly to one innocent protester holding a sign than the instigators of thousands of liters of blood clogging the fragile drainage system, overwhelming the minimal sanitation standards and releasing the smell of dead animals into the air.

The withering of Islamic ethics regarding the practice of slaughter is obvious when basic questions are not even asked as to why animals are kept in dire conditions in the lead-up to their fate, why they are forced to witness others being slaughtered and why are children watching this bloodbath. What is halal anymore?

Moreover, the implication is that the animal is the centerpiece of the festivity, obscuring the underlying message and normalizing our problematic addiction to meat.

Meat consumption was extremely limited in the early days of Islam. The Prophet and his companions were semi-vegetarians. One, in fact, was an outright vegetarian. The sources consistently showed the Prophet’s favorite foods to be dates, barley, figs, grapes, honey and milk, among other non-meat foods. The Prophet never ate beef, going as far as saying, “The meat of a cow produces sickness, but its milk is a cure.” The Caliph Omar warned to, “Beware of meat, because it is addictive like wine.” Historically, it was only rich Muslims who could afford meat, and it would only be eaten on Fridays, while the poor had to wait for Eid to eat meat.

These historical factors ought to be considered in light of the need to reframe Eid Al-Adha away from the morass it has been dragged into. Perhaps meat can be treated as that rare luxury that is eaten infrequently across the social strata. I’m no vegetarian, but the excessive quantity of meat produced and consumed, the social signifiers that accompany it, the deep inequalities that it sharpens and the troubling medical problems that it exacerbates, not to mention the additional pressure meat production places on the planet, means that there is an urgent need to diversify cuisines and elevate non-meat options.

Whatever is happening, it is no longer about the story of Abraham, it is something that you just do because you did it last year and you will do it next year as well.

More and more, each year, we experience a nihilist Eid on the streets. The butchers don’t know why they are slaughtering, the donors don’t know why they are paying for it, the public doesn’t know why they are witnessing it, and the sermons have hit a tone-deaf level. The only ones who seem to have some awareness that something is not quite right are the sheep, goats and cattle.

I have noticed over the past year that archival footage on Egyptian history and post-2011 videos on Egypt’s events are (mysteriously?) disappearing from YouTube, even when the issue could not be one of copyright. Similarly, the vanishing act is reportedly happening to content produced in other Arab countries. A video that is deleted is an assault on our collective memory and our post-2011 quest to build an unfettered archival culture (despite how contested archives can be).

We have long taken for granted that a video on YouTube was left untouched unless it violated copyright rules like a song, TV program, or film. It was always assumed that historical footage, even the most mundane type to the authorities like 1950s village life, would be unharmed given it posed no political threat. However, even these videos are fading. We can no longer take for granted that such videos will remain in perpetuity.

The four possible reasons for this that I can think of include:

Irrespective of any reason, the end-result is the same and fits a pattern: The authoritarian attempt at drowning Arab publics in the mythical river of Lethe (forgetfulness).*

How can the situation be resolved? For the time being, and I say this with a sense of urgency, if you think a video is worth saving for posterity, then it would be wise to download such videos through this link: http://www.clipconverter.cc

It’s quite a simple three step process. This is the most important step even if you don’t carry out the next steps. In any case, you will probably require these videos in some personal or work capacity in the future.

The next step is to make it accessible by uploading it to Google Drive, OneDrive, DropBox etc, and setting access permissions for that specific folder or video to public. Then notify the web by sending out the link and using the hashtag on social media: #SaveArabHistory (Or any universally agreed hashtag).

This is an ad-hoc approach until there is a concerted, organised and collective way to preserve, catalogue, and offer video access for offline and online use. But once they are gone, they are gone! There is no guarantee that the original user (who may have passed away) will upload them again or can be contacted. If there are already existing initiatives doing this, then they are welcome to advise and get involved.

When I assign my sociology students certain videos to watch but it turns out the respective videos have perished, then it not only means my students have been partially deprived of a comprehensive understanding of their subject matter (which is worrying enough), but the way we deal with technology, in an era that is seeing censorship and blocked websites slowly normalised, needs to change.

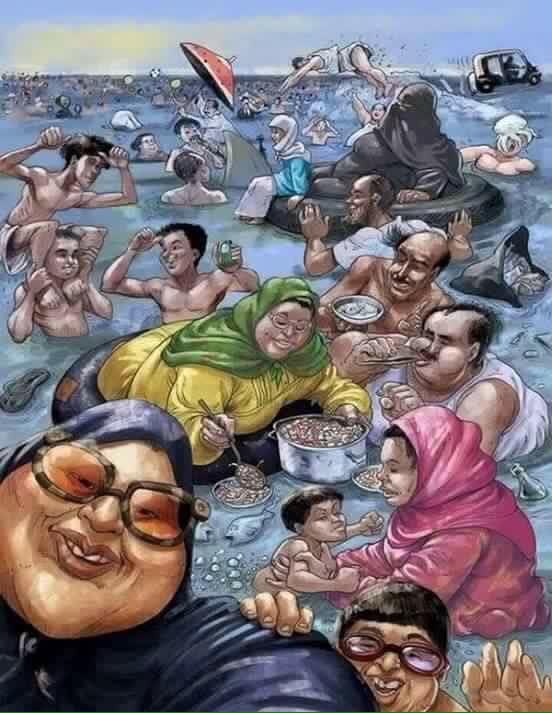

It’s that time of year, the “let’s dehumanise the Fellahin” season (or any rural visitor for that matter), as they escape the villages for some summer relaxation in Alexandria. The above-circulated caricature feeds into all the vile remarks made daily about the Fellahin, and echoes their ill-treatment on the corniche.

Let’s just go through three of the tired and misleading statements that Alexandrian residents frequently make.

1. “Fellahin make a mess of the beaches and the city.”

Because Alexandria is generally clean the rest of the year? The issue here is a lack of rules being applied and the shrinking public beaches that forces them to squeeze into tinier plots of public beaches. This is a governorate problem.

2. “Fellahin are the worst sexual harassers.”

Because Alexandrian sexual harassment is more refined? Nothing beats winter sexual harassment? By making such accusations, the responsibility is shifted away from the rule of law being applied equally to all, in order to fight harassment, and pushed, rather towards a particular group. This is a governorate problem.

3. “As soon as they arrive, I’ll leave Alex” or “they need to put a fee of 50 pounds at the city’s gates to reduce the numbers coming into Alex.”

The obvious bigotry and classism aside, putting blame on the citizen for over-population and lack of public space will continue to give a green light to the businessmen and mafia who keep eating up what is left of the city’s spaces. Once again, this is a governorate problem.

Don’t forget that similar insults were hurled at middle-class Cairenes who came in the summer up until the 1980s, that is before they gradually decided Sahel, Ain Sokhna etc were more fitting. It seems allowing rural visitors and the poor to access the sea, often for the first time, is beyond many to even contemplate.

Perhaps this denial of their rights can be put in perspective. The below photograph shows two middle-aged Ṣa’īdi men seeing the sea for the first time in their lives. They slowly entered the water with a profound curiosity and glee, and when I asked them how it felt, one turned around and shouted with a big smile: “meya meya!” (a hundred out of a hundred).

With all the economic misery and hardship that Egyptians, especially the poor, are enduring, do you really want to be complicit in the web that worsens their plight? By denying them their right to view, touch and enjoy the sea? To deny them access to the last remaining strongholds of beauty that has already been mostly privatised?

Originally published in Ibraaz

II. On Nation Building: Alexandria, Egypt.

Mahmoud Khaled in conversation with Amro Ali

I have been familiar with Mahmoud Khaled’s artistic works for a number of years, and his creative output never fails to astound the observer. Alexandria, the city we both herald from, can often be a political tempest and urban dystopia that deepens a chronic melancholia within the public realm. This, in turn, foments nostalgia through the citizenry who long to live in a sepia-tinged so-called golden age. What romance is to Paris and ambition is to New York, nostalgia is to Alexandria. Yet perhaps because the city functions in a world of intangibles, one where the mythologized metropolis is drowned in a long glorious history that torments the human imagination; will as a result, ruthlessly press the artist, poet, writer, and thinker against established boundaries; at times breaking them.

Political theorist Fredric Jameson noted that nostalgia is an ‘alarming and pathological symptom’ of a modern world unable or unwilling to engage in any meaningful way with its own historicity. This is where Khaled’s work comes in: he seeks to engage this symptom by confronting the Alexandrian spectre of memory. His latest work A New Commission for an Old State (2016) propels the progenitor of nostalgia, memory, into a new site-specific exhibition. A form of commemoration that embodies complex narratives in the young artist’s new body of work, through three iconic artefacts within the Egyptian context.

The first is a gated summer resort in Alexandria called Maamoura built by the state shortly after Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power to accommodate the new elite of the ‘rebranded’ (post-1952) Egypt. The second is a landmark text titled Maamoura’s Victims written by Judge Hassan Jalal who was a harsh critic of the Egyptian monarchy. The third artefact is a 1961 film by Youssef Chahine titled A Man in My Life, which started production in Maamoura a few months after it officially opened in 1959. The story revolves around the life of a fictitious architect who is known for his remarkable modernist style and who has built one of Maamoura’s most memorable buildings, which is used as a backdrop in the opening scene of the film.

Mahmoud Khaled, A New Commission for an Old State, 2016. Detail, C Photograph (15cm X 10cm). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Mahmoud Khaled, A New Commission for an Old State, 2016. Detail, C Photograph (15cm X 10cm). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Amro Ali: Your recent solo exhibition in Germany last summer is highly fascinating and it certainly overlaps with my work in political sociology. The driving question that intrigues me is: Where does Alexandria, as an autonomous entity, fit in the artistic narrative that you have developed? My understanding of Nasser-era rebranding has more to do with how Alexandria was divorced from its Greco-Roman heritage, and pushed more towards its Arab heritage. I don’t see this as a phenomenon that happens immediately after 1952, but rather gains traction in the 1960s when, for example, Alexandria saw the rise of statues of Arab figures in the public space such as Ibn Khaldoun and Sayeed Darwish, among others. How does the rebranding in Mammoura fit in with this? When you speak of re-branding, is it a matter of the state homogenizing the entire landscape across the country, without any consideration for local factors and idiosyncrasies of a city?

Mahmoud Khaled: I also don’t see this rebranding as happening immediately after 1952. As you said it did take almost a decade for this process to physically and visually exist in the public sphere and Mammoura as a project is evidence of this, as it officially opened in 1959 and was promoted afterwards as one of the regime’s achievements towards the promised social democratic state and assuring the official support to the middle, working class and farmers.

We also know, this rebranding process was not only about erecting buildings with new architectural aesthetics and sculptures of significant Arab and national figures in public spaces, but included the establishment of agrarian reforms and ambitious industrialization programs that led to a period of infrastructure building and modern urbanization. There was a political need to have these social and architectural projects to form a new Egyptian identity that served the new elite of the republican era. Theses projects included housing complexes, theatres, cultural palaces, parks and summer resorts. Architecturally, aesthetically and functionally, then, all these projects were designed in sharp contrast to the lavish lifestyle of the former royal aristocracy which added a strong political connotation to the style of these buildings and projects, and more generally to the introduction of ‘Modernism’ in Egyptian architecture. At least that’s how I understand it.

Maamoura is located strategically next to the former royal Montaza palace and gardens, which I read as an intentional political statement to show that the new state can also design and build a protected gated space for its won elite. This beach resort is considered to be the prototype for modern bourgeois summer destinations and is one of the first gated community projects in Egypt, functioning as a city within the city with its architecturally unique residential villas, houses, and cabins mostly owned by generals, businessmen, and celebrities that came to form the new upper class. At the same time, more modest buildings were targeted towards the middle-class with public sector companies having access to properties that they rented out to their staff for affordable prices.

Mammoura Beach, Alexandria, 1995. Black and white promotional video of Al Mammoura resort project, found on YouTube.

AA: The problem of political branding is that it tends to destroy pluralism, as the state imposes a narrative from above, rather than allowing an organic story to develop through civil society. How does your understanding of branding, in an architectural sense, equate with oppression and the destruction of civic meaning?

MK: Personally, I don’t see any contribution from the civil society in this whole process at all; everything was done by the state to the people, and mainly most of the projects were executed by the army itself which is something happening until now and my generation can definitely relate to it.

Mahmoud Khaled, A New Commission for an Old State, 2016. Installation view at Edith Russ Haus für Mediakunst, Oldenburg. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Mahmoud Khaled, A New Commission for an Old State, 2016. Installation view at Edith Russ Haus für Mediakunst, Oldenburg. Photo courtesy of the artist.

AA: You touch upon an important aspect regarding Youssef Chahine’s films. From my readings, the struggle between Alexandria and the state extended to films: for example, Nasser-era cinema tended to reflect narratives that domesticated Alexandria. This in turn subverted the city into the national narrative. Chahine’s films were not an exception, although it as only with his 1978 film Alexandria, Why? that he was able to challenge this trend, by breaking with the conventional narrative and realigning it with an emerging novel tradition that represented Alexandria as a place of “utopian desire.” The renowned director started to see a relative change in the political culture of 1970s Egypt – if not the Arab world – that enabled his cinema to “recognize and redress marginalized social elements within Arab national identity…[by revisiting and engaging] the cultural and historical elements of distinct groups he thought integral to the appreciation of a collective Arab identity.”[3]

In light of this, how much innovation and independence was Chahine allowed in the making of the 1961 film A Man in my Life? Was the film geared towards supporting Nasser’s project? Or did Chahine situate the idea of justice in a national (or perhaps nationalist) narrative at the expense of local civic factors?

MK: I think in this film Chahine tried to abstract the ideologies and the principles behind the “free soldiers” movement by staging a melodramatic love story that contains a lot of guilt, pain, and heroism to highlight the struggle for social justice amongst the working class (here, a group of fishermen in Alexandria) in the year of 1938, when the country was still a royal monarchy. It is very obvious to me how he was very influenced by these ideas, principles, and hopes for the establishment of a modern and socially equal state, like many other artists and intellectuals in Egypt at the time. For example, I still remember many of my painting professors in Alexandria who are associated with or known as the sixties generation of artists, were preoccupied with producing art that was heavily engaged with the ideas of social justice, class struggle and full independence from colonialism. I honestly don’t think these artists, including Chahine, were doing this work to compliment the political power, or as a sort of a contribution to the propaganda of the new regime. Rather, I think they – or let’s say most of them – believed in these ideas and wanted to dedicate their production to contribute to the cause.

This is, in fact, the most interesting point for me: how can we now look back at the art production of this period, especially given the radical shifts since 2011, to how we understand the regime today? How does viewing the situation as a continuation of the 1952 state, reshape our relationship with our home country?

In terms of innovation, I am not sure to what extent the film was an original, given it was an adaptation of the 1954 American film Magnificent Obsession by Douglas Sirk, But I am personally not so crazy about this idea of originality; I find it clever how Chahine kept the structure of the story from Sirk’s film but adapted the sociopolitical content in order to respond and engage with the political and ideological moment in Egypt at the time.

Video collage by Mahmoud Khaled of two films, both of which were important source material for him during the formulation of this comission: A Man in My Life, dir. Youssef Chahine, 1962, Egypt, and Magnificent Obsessions, dir. Douglas Sirk, 1954, USA.

AA: Fascinatingly, this recent body of work metaphorically touches upon building materials such as glass and marble, which you argue have been widely utilized in state-sanctioned architectural projects in Egypt over the past thirty years. Here, I specifically want to point to the piece A Rare Glimpse into the Recent Moments When People Lived in a World Turned Upside Down (2016) in which you used eight computer-generated images of carrara marble printed on wallpaper and sixteen double glass panels, accompanied by images and texts that occupied almost half of the space of the exhibition.

Is there a particular state logic behind utilizing building materials such as glass and marble? Does this have any relationship to Mubarak’s political projects and neoliberal policies?

MK: Yes it does. I wanted to do something physical, imaginative and semi-fictional, using material that would speak directly to the content of the installation. I decided to use the format of the memorial as a site from which to stage the content of the project; of course here, marble makes perfect sense, as a permanent noble and monumental material that has been used excessively in most of the governmental projects in Egypt during the past thirty or so years, which is of course, the era of Mubarak.

When I looked back at the use of the material and its existence in state-owned or run buildings, I started to see the sharp contrast between marble and the kind of modest, humble and relatively cheap building materials that was used in the late 50s and 60s by the regime. For me, this shows how the state wanted to manifest itself and assert it’s power architecturally and in public spaces, whilst pointing to the shift in aesthetics and values from the 60s to the 90s, and so I was keen for the installation to reflect this.

AA: The ‘Maamoura’s Victims’ text by Judge Hassan Jalal, published in Al Hilal Magazine in February 1955 just few years after the ’52 state’ started, presented a report on the atrocities, horrendous conditions and systematic tortures in a prisoner camp on the King’s properties, which later became the land on which Maamoura was built. It is an insightful artifact from a very romanticized period in the Egyptian and Alexandrian popular imagination. Would you say that your work in this regard is a strong statement against nostalgia?

MK: William E. Jones, who is one of my favorite artists said recently in an interview that ‘Nostalgia is a sympathetic feelin’‘[4] – and I completely agree with him.

Unfortunately, Alexandria has been always romanticized in the popular imagination. I can even sense this when I talk about the city with my friends and colleagues from Cairo. It’s something I used to be very sensitive about it. Nostalgia became the scary ghost that I tried to kill while I was developing and working on the exhibition, and I hope I did that – though I don’t know. I think the problem for us Alexandrians is that we have been over saturated with nostalgic narratives and representations of the city in books, films, and photographs (and now even on social media) but it’s still the city we live and work in. And so, it is hard to ignore the overarching sentimentality.

That is why I tried for a long time to avoid working on anything related to Alexandria and its history – near or far – because you can never escape the language and aesthetics of nostalgia when talking about the city in the field of artistic and cultural production. This idea shifted for me in 2011, when I saw everything in the city becoming highly politicized and very active, instead of being forever decaying and romantic; it was then that I realized that I can talk abut the city in a way I was unable to before, mainly because of my own self-censorship towards this fear of being nostalgic.

Jalal’s text was also a huge discovery for me – it made everything feel similar and yet different all at once, and that’s why I wanted to use it in full length in the installation. First of all, it gives us a glimpse of Maamoura when it was just an empty, neglected wasteland, and how even during this time (late 1940s/early 1950s) it was a stage for human rights violations, torture and the exertion of power by the state. Secondly, the fact that it was written by a judge, whose profession is to protect the values of social justice and dignity in society, he is also fully supporting the 1952 state (which I believe we are still living an extension and the continuation of this era).

I also think my fascination with the text has a lot to do with the fact that I was born around a bunch of structures, monuments, and buildings which are gradually vanishing from the cityscape, yet I still don’t know much about the socio-political history of Maamoura or how things were before these structures were built. At the same time access to information as an artist or a researcher is restricted by state authorities; you will find a lot of intentional obstacles in your way, so as not to ask or uncover anything that may conflict with the state-sanctioned narrative. Here, the act of knowing becomes a highly politicized endeavour and pushes this persistent nostalgia out of the frame.

AA: The use of the Maamoura’s Victims as a textual document/ testimony is described in the exhibition text as an element that is highlighting and activating the “haunting similarities” between the methods of the monarchy and republic, which you argue, puts the document in a completely different light, making it even more relevant when read in the present. Based on this reading, I would like to ask: could not the observer of your work suggest that in attempting to condemn the monarchical period as being just as bad as the republican era, you have indirectly vindicated the latter? Historians would probably not disagree with your account, but they could argue that oppression and torture increased exponentially and systematically under the Nasser regime, making the King Farouk era pale in comparison.

MK: Well, I don’t think the work is trying to vindicate or blame one era or another as both eras are very difficult to understand or judge in their entirety. I also hope the artwork works to complicate and problematize moments in our history, instead of just giving a statement about who was more oppressive than the other, because things are far more complicated than this. This is especially the case for artists; perhaps it is easier for researchers, academics, and historians because they have a clearer methodology for how to draw their conclusions. Yet for most of us – and by us, here I mean the artists whom I am close to and am in dialogue with – we are all producing and speaking from a position in a world that does not make any sense at all, and art seems for some of us, still the only possible long-term attempt to deal with this mess that we are collectively sharing.

The work is imagining a memorial, a space for remembrance, which as an act includes thinking and reflecting with a strong sense of monumentality and spectacle. Memorials are traditionally built after long civil and grassroots discussions, and to remember key social and political events. Yet my generation only inherited memorials; we never experienced or witnessed the building of those we inherited, and so the aim of my work is to both consider and commiserate the absences in constructing our own history, emotionally and meaningfully.

Mahmoud Khaled (b. 1982, Alexandria, Egypt), lives and works between Egypt and Norway. He studied fine art at Alexandria University in Egypt and in Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway. His work traces the boundaries between what is real and what is hidden, disguised or staged. His artistic practice is both process oriented and multidisciplinary. Mixing photography, video and wall painting with sculptural forms, sound, and text, his works can be regarded as formal and philosophical ruminations on art as a form of political activism, as an object of desire and as a space for critical reflection. His artistic vocabulary is composed of appropriated forms that have been displaced from their original context thereby proposing alternative meanings.

Khaled’s work has been presented in solo and group exhibitions in different art spaces and centers in Europe and the Middle East, including Whitechapel, London (UK); Edith-Ruth-Haus, Oldenburg, Germany; BALTIC Center for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK; Galpão- Videobrasil, São Paulo, (Brazil); Gypsum Gallery, Cairo, (Egypt); Centre Pompidou, Malaga, Spain; Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (SMBA), (Netherlands); Bonner Kunstverein, (Germany); UKS, Oslo, (Norway); Salzburger Kunstverein, (Austria); Contemporary Image Collective/CiC, Cairo, (Egypt); Sultan Gallery, (Kuwait). His projects have been featured in several international biennales such as LIAF Biennale, Lofoten, (Norway). BManifesta 8: European Biennale for Contemporary Art; Biacs 3, Seville Biennale, and 1st Canary Islands Biennale, Spain. In 2012 Khaled was awarded the Videobrasil In Context prize and he was shortlisted for the 2016 Abraaj Art Prize.

[1] Alexander Reid Ross, ‘A New Chapter in the Fascist Internationale’ in CounterPunch, 15 September 2015: http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/09/16/a-new-chapter-in-the-fascist-internationale/

[2] ‘Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.’ The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx 1852.

[3] Malek Khouri, The Arab National Project in Youssef Chahine’s Cinema (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2010). 117.

[4] Quoted in Mousse Magazine. Issue 56. December 2016–January 2017