I’m glad to announce a new course that I will be teaching at the AUC this Spring, Alexandria: Mobs, Publics, and Enduring Imaginaries. With a substantial focus on the contemporary period. As usual, I always welcome non-enrolled students to attend the sessions.

Category: Essays & Articles

“Read not the Times. Read the Eternities. Knowledge does not come to us by details, but in flashes of light from heaven” – Henry David Thoreau

Vita Activa and Vita Contemplativa: Reading Hannah Arendt in Egypt (Public workshop)

This workshop will explore the philosopher Hannah Arendt’s themes of Vita Activa (Active Life) and Vita Contemplativa (Contemplative Life) and the ways it can be weaved into intellectual, research, and cultural endeavors within Egypt. The workshop is run by AUC HUSSLab’s postdoctoral fellow, Amro Ali, and Tahrir Lounge Goethe director, Mona Shahien. The event is free and open to the public, 6pm to 8pm, Wednesday, 28 November 2018, at AUC Tahrir campus, Hill House 602. Click here for the Facebook event.

Thinking in the Swarm: When Awareness and Knowledge Succumb to the Information Deluge (Public lecture)

The final Theatre of Thought lecture for 2018 will take place on 22 November 2018 at the Goethe-Institut Alexandria. This sociological-philosophy series will present: “Thinking in the Swarm: When Awareness and Knowledge Succumb to the Information Deluge.” Click here for the Facebook event.

The rise of the information age and digital revolution gave hope that immediate access to a plethora of sources, interactive and always visible, was within easy reach. In many respects, this was an encouraging development in places like Egypt, where libraries and access to books were rare or difficult to for the public. However, it came at a price. In 1996, British psychologist David Lewis coined the term Information Fatigue Syndrome (IFS) after noticing that workers who dealt with vast quantities of information were suffering from a weakening of their analytic capacity, attention deficits, inability to bear responsibility and traits of depression. It was unimaginable that this rare condition at the time would eventually engulf, in various degrees, the entire world. With the inundation of information, boiling matters down to their essence has become an arduous task.

The Theatre of Thought continues with the works by German-Korean philosopher Byung Chul-Han who argues that “on its own, a mass of information generates no truth. It sheds no light into the dark. The more information is set free, the more confusing and ghostly the world becomes. After a certain point, information ceases to be informative. It becomes deformative. Simply having more information and communication does not shed light on the world. Nor does transparency mean clairvoyance.” Thinking is underpinned by discernment, discrimination, selection, and even forgetfulness – qualities that are frequently bulldozed in the online world.

However, this is not about fleeing from the digital realm as much as it is to ask the question: How do we reconcile the digital order with the terrestrial order? The German theorist Carl Schmitt celebrated the earth for its solidity which enabled clear demarcations and distinctions in which character is formed. Whereas the digital order equals the “sea,” where “firm lines cannot be engraved”, that is to say, no character. The smooth open spaces of the digital medium are without end, but a better appreciation of the world of shadows with its nooks, corners, crannies, and alleys that not only filter and impede the information pollution and trolls, but allows slowness, reflection, and mediation processes back into the thinking fold and the realm of authenticity.

الوعي والمعرفة أمام طوفان المعلومات

لقد بعث عصر المعلومات والثورة الرقمية الأمل في النفوس بأن عالمًا من الموارد الوفيرة – المرئية منها والتفاعلية – قد أصبح بين أيدينا. وكان ذلك تطورا مشجِّعا من نواحٍ عِدة في دول مثل مصر، حيث كانت المكتبات قليلة وفرصة الجمهور في الحصول على الكتاب نادرة. لكن الثمن كان كبيرا. ففي عام 1996، خرج الإخصائي النفسي البريطاني ديفيد لويس بمصطلح “متلازمة الوهن المعلوماتي” (IFS)، بعد أن استرعى انتباهه أن العاملين الذين يتعاملون مع كم هائل من المعلومات يعانون من ضعف في القدرة التحليلية ونقص في الانتباه، وعدم القدرة على تحمل المسئولية، بالإضافة إلى ظهور أمارات الاكتئاب عليهم. ولم يخطر ببال أحد عندئذٍ أن تلك الحالة النادرة سوف تسري بين البشر في أنحاء العالم كافةً حتى تلتهمهم جميعا ولو بدرجات متفاوتة. ومع الإغراق المعلوماتي، صار تحليل أي مسألة من أجل الوصول إلى جوهرها مهمة شاقة.

يواصل مشروع التحرير لاونج جوته رحلته مع “مسرح الفكر” الذي يقدمه دكتور علم الاجتماع عمرو علي، بعنوان “الوعي والمعرفة أمام طوفان المعلومات”، وذلك بأعمال الفيلسوف الألماني-الكوري بيونج تشول هان، الذي يؤمن بأن كتلة المعلومات وحدها لا يمكن أن تتولد من بين طياتها الحقيقة؛ فهي لا تشع نورا يبدد الظلام، بل إن كل سيل من المعلومات ينطلق باعثاً معه حالة من التشويش يستحيل معها العالم عالماً للأشباح، وفي لحظة ما ستصبح المعلومات عاجزة عن تنويرنا أو إعلامنا بشيء؛ بل سوف تنتقص مما لدينا من معرفة؛ فالحصول على مزيد من المعلومات، وتحقيق مزيد من التواصل لا يجعل العالم أكثر وضوحا ولا استنارة، ولا الشفافية تعني وضوح الرؤية، حيث أن التفكير يرتكز على الإدراك والملاحظة والتمييز والانتقاء، بل وحتى على النسيان – تلك عمليات يتم تدميرها والإجهاز عليها في عالم الإنترنت.

كما تتناول الندوة فكرة أنه رغم كل ذلك، فالأمر لا يُعد دعوة للهروب من العالم الرقمي، بل دعوة لكي نسأل أنفسنا: كيف لنا أن نحقق التصالح بين النظام الرقمي، والنظام الأرضي؟ لقد عبر العالم الألماني كارل شميدت عن أن عظمة الأرض تكمن في صلابتها، حيث رُسمت الحدود وَوضَحت الفروق، فصنعت ملامح شخصيتها المتفردة، بينما يترامى النظام الرقمي “كبحر بلا شاطئ”، يستحيل فيه “أن تحفر خطًا واحدًا”، أي لا شخصية له على الإطلاق، كما أن الفضاءات الشاسعة الناعمة التي يفتحها الوسط الرقمي أمامنا لانهائية، لكن إذا تيسر لنا أن نتذوق عالم الظلال بأركانه وزواياه وشقوقه المظلمة وأزقته الضيقة، إذن لتمكننا من تنقية المعلومات وصد الملوث منها، وقطع الطريق على الغيلان القابعة فيها، بل ولحظينا ببعض الفرصة للتمهل، والتفكُّر، والتأمل -الشيء الذي سيعيدنا إلى مساحة التفكير وإلى عالم الأصالة.

تقام الندوة يوم الخميس 22 نوفمبر بمعهد جوته بالإسكندرية من الساعة 7 وحتى 9 مساءً، وتدير الندوة مؤسسة ومديرة مشروع التحرير لاونج جوته منى شاهين.

الدكتور عمرو علي هو دكتور علم الاجتماع في الجامعة الأمريكية بالقاهرة، محاضر في العديد من الجامعات والمعاهد في القاهرة والإسكندرية، تتناول أبحاثه دراسة المجتمعات، والحالة الإنسانية في ظل الاعتداء من قوى الاستهلاك العالمي والثقافة المادية، وآثر ذلك على الهوية، ومعنى المدينة والحداثة والمواطنة، حصل على الدكتوراه من جامعة سيدني وكانت الرسالة البحثية الخاصة به عن دور الخيال التاريخي في تشكيل الإسكندرية الحديثة ومواطنيها.”

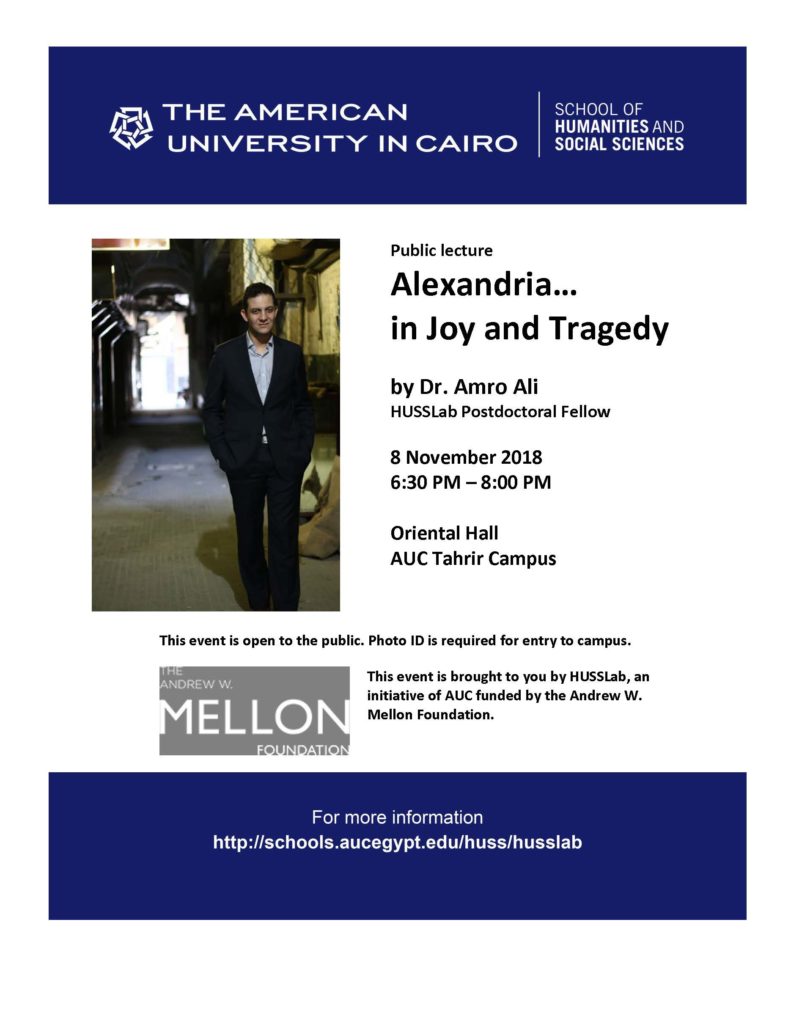

Alexandria in Joy and Tragedy – (AUC public lecture )

This lecture will trace the historical and contemporary forces that shape the idea of civic joy and belonging in Alexandria, and its unravelling in recent decades under the weight of centralization, an illegal building craze, brain drain, consumerism, privatization, the slow vanishing common narrative, and, above all, the disintegration of the public space. The seminar will also explore the characteristics and implications of a peculiar despair across a growing swathe of the Alexandrian citizenry that is manifesting itself through a shared agony that glances around for answers, sensing that time is slowing down again, desiring to live in the past, and developing an obsession with any object that represents loss.

Click here for the Facebook event.

Click here for the Facebook event.

Ambiguous Promises and the Fragmentation of Responsibility (Public lecture)

The next Theatre of Thought lecture, Ambiguous Promises and the Fragmentation of Responsibility, will take place on 1st November 2018 at Goethe’s Tahrir Lounge. The session will be in Arabic.

Click here for the Facebook event. “Responsibility has traditionally meant a duty of care to someone or power over something, a moral obligation to act deferentially to another, and to be held accountable for the good or bad that might unfold under one’s control. These meanings typically aggregate and animate within the idea of a citizen. Yet in recent decades, the undermining of responsibility was soundly argued to be the fault of the consumer encroaching on the citizen category. Responsibility, the hallmark of the citizen, is being degraded by the consumer that lacks responsibility due to the tendency to follow personal inclinations. However, these blurred lines simply paved the way for the problems of the digital age that are exacerbating the diminishing of responsibility.

“Responsibility has traditionally meant a duty of care to someone or power over something, a moral obligation to act deferentially to another, and to be held accountable for the good or bad that might unfold under one’s control. These meanings typically aggregate and animate within the idea of a citizen. Yet in recent decades, the undermining of responsibility was soundly argued to be the fault of the consumer encroaching on the citizen category. Responsibility, the hallmark of the citizen, is being degraded by the consumer that lacks responsibility due to the tendency to follow personal inclinations. However, these blurred lines simply paved the way for the problems of the digital age that are exacerbating the diminishing of responsibility.

The notion of responsibility is dependent on temporal conditions and the supposition of obligations that make acts of trust, promise, and forgiveness possible in order to heal the past and stabilize and secure a steadfast future. However, what does it mean for responsibility when today’s digital communications are perilously thrusting the individual into a world of arbitrariness, non-binding obligations, and short-term gains? Rapidly, responsibility is torn from its past and future commitments as the present is pushed as the absolute priority and, therefore, it is scattering time into, as German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han would argue, ‘a mere sequence of purely disposable presences.’

This seminar will explore further questions of consequence. Among them, if it is possible to delineate the features of passivity that overwhelms responsible agency? Does the slow brewing of trust required to form a mature social praxis lose meaning when hyper-visibility is all-pervasive, privacy is suspected, and rapid information access is readily available? or given that responsibility is tied to names and naming in order to confer recognition, then what are the implications of perceiving the other, in terms of trustworthiness and reliability, when they are dissolved in a digital swarm?”

—–

يستكمل مشروع #التحرير_لاونج_جوته سلسلة حلقات #مسرح_الفكر الموسم الثاني بخامس حلقاته ومحاضرة تحت عنوان “النفاق وتفتيت الشعور بالمسئولية”، والتي سيتناول فيها المتحدث بالندوة د. عمرو علي موضوع المسئولية بأشكالها في العصر الحديث، والاثار المترتبة على تطبيقها في ظل العصر الرقمي الذي نعيشه الان.

تعني المسئولية على نحو تقليدي واجب الرعاية لشخص ما أو السلطة على شيء ما، التزام أخلاقي للتصرف بشكل مختلف عن الآخر، وتحمل المسؤولية عن الخير أو الشر التي قد تتكشف تحت سيطرة المرء. هذه المعاني عادة ما تكون مجمعة ومتحركة في إطار فكرة المواطن. لكن في العقود الأخيرة، قيل إن تفويض المسؤولية كان خطأ المستهلك الذي ينتهك فئة المواطن. إن المسؤولية، السمة المميزة للمواطن، تتعرض للتدهور من جانب المستهلك الذي يفتقر إلى المسؤولية بسبب الميل إلى اتباع الميول الشخصية. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه الخطوط غير الواضحة مهدت الطريق ببساطة لمشاكل العصر الرقمي التي تؤدي إلى حدة تناقص المسؤولية.

يعتمد مفهوم المسؤولية على الظروف الوقتية وفرض الالتزامات التي تجعل أعمال الثقة والوعد والمغفرة ممكنة من أجل مداواة الماضي وتحقيق الاستقرار وتأمين مستقبل راسخ. ومع ذلك، ما الذي تعنيه المسؤولية عندما تكون الاتصالات الرقمية اليوم هي التي تدفع الإنسان إلى عالم من التعسف والتزامات غير ملزمة ومكاسب قصيرة الأجل؟ بسرعة، انشقت المسؤولية عن التزاماتها السابقة والمستقبلية، حيث يتم دفع الحاضر كأولوية مطلقة، وبالتالي فإن الوقت قد بدأ يتناثر، كما يقول الفيلسوف الألماني-الكوري بيونغ-شول هان، “مجرد تسلسل للوجودات التي يمكن التخلص منها على نحو مجرد.”

هذه الندوة -التي ستنعقد يوم الخميس 1 نوفمبر الساعة 7 – 9 مساءً بمقر مشروع التحرير لاونج جوته- سوف تكشف العديد من الأسئلة الناتجة. من بينهم، إذا كان من الممكن تحديد ملامح السلبية التي تكتسح الوكالة المسؤولة؟ هل الثقة البطيئة المخمرة مطلوبة لتشكيل تطبيق عملي اجتماعي ناضج تفقد معنى عندما تكون الرؤية الفائقة منتشرة، الخصوصية مشتبه بها، والوصول السريع للمعلومات متاح بسهولة؟ أو إذا كانت تلك المسؤولية مرتبطة بأسماء وتسمية من أجل منح الاعتراف، ثم ما هي الآثار المترتبة على إدراك الآخر، من حيث الثقة والدقة، عندما يتم حله في سرب رقمي؟

Unpacking Self-Expressions in the Modern Era (public lecture)

The third season of the Theatre of Thought will commence at Goethe’s Tahrir Lounge on 11 October 2018. The first lecture I’ll be giving is titled “Unpacking self-expressions in the Modern era” (the talk will be in Arabic).

Click here for the Facebook event link.

“Body language, art, fashion, and hairstyles, are some of the familiar modes of self-expression, but in an age of hyper-visibility and inter-connectedness, self-expression has accelerated to become one of the highest articulation of individuality and novelty. Self-expression in some respect is beneficial to crystallize the forces that go into constructing the individual’s expressive identity at a point in time and place, as well as fleshing out a positioning in relation to a world that has become increasingly noisy and blurred. This lecture, however, will explore how in recent decades, in Egypt and abroad, consumer culture has appropriated self-expression, in the midst of the neoliberal storm that’s turning citizens into customers, that it has become increasingly difficult to separate self-expression from the shadow of monetary manipulation. It raises further questions, among them, if self-expression does in fact disguise a different set of established rules and practices, and at one point does non-conformity begin to look quite similar?

Since the 1970s, self-expression grew as the new style of challenging the problems and toxins in the world, but this is becoming somewhat futile when the whole world seems to be moving towards basing itself on self-expression. The reduction of self-expression to feelings and consumer desires has severed the idea of self-expression from any possible higher ideals and the notion that you can be part of anything bigger than yourself. Moreover, self-expression masquerades as a new radical way of seeing or understanding the world, but a mature worldview is arguably unable to crystallize from simply talking about the self and feelings towards the other.

The end result, as Berlin-based South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han observes, is the terror of the same, a world of unceasing repetition of similar experiences pretending to be novelty and renewal. This also consequently sees the ideas of love, bonding, solid relations, responsibility, and communal spirit, collapse in a world further burdened by an endless freedom of choice, oversupply of options and the compulsion for perfection. That is to say, self-expression robs countless hours as a result of choosing the right clothes, embellishing and updating the right Facebook photo, and cultivating special friendships for the self, not the relation, to be projected upon. All so one can participate in the worldly spectacle that sees a global collection of individuals that have moved away from reflection, contemplation, sustained efforts at doing one task, while distraction becomes the norm and the interior of the self is hollowed out.

لغة الجسد والفن والموضة وقصات الشعر هي الطرق المعروفة للتعبير عن النفس. لكن في عصر ال” الأعلى مشاهدة” و”التواصل المتشابك” تطورت فكرة التعبير عن النفس لتصبح الإفراط في الذاتية وطرحها بشكل مبتكر .

إن التعبير عن النفس هو تبلور لكل عناصر بناء الشخصية التي نود التعبير عنها في مكان ووقت معين وعلاقتها بعالم يزداد في الصخب وعدم وضوح الرؤية.

في هذه المحاضرة نبحث في العقود الحالية في مصر والعالم عن كيف استغلت الثقافة الاستهلاكية فكرة التعبير عن النفس وتحويل المواطنين إلى مستهلكين مما يجعل فكرة التعبير عن النفس بعيد عن البعد الإقتصادى، شيء في غاية الصعوبة. وهنا نطرح أسئلة أخرى مثل: هل التعبير عن النفس في حد ذاته يتقيد بقوانينه وممارساته الخاصة وهل يعبر عما في أنفسنا حقا؟.

منذ السبعينات والتعبير عن النفس بدأ في النمو بالتوازي مع التحديات التي تواجه العالم ولكن للأسف هذا التعبير عن النفس لم يثمر عن شيء حين اقتصر هذا التعبير على المشاعر والاستهلاك فخلت الفكرة من أن نكون جزءًا من شىء أكبر منا. كذلك فكرة التعبير عن النفس في حد ذاتها ومحاولة فهم العالم في حد ذاتها فكرة راديكالية لكن رؤية العالم لا تبنى من منظور فردي.

في نهاية الأمر كما أكد الفيلسوف الكورى بيانج شيل هان، وينتج كل ما سبق “النمطية المفزعة” في عالم يكرس للتكرار وإن تخفى في صورة تجديد وامتداد. هذا التكرار يجعلنا نرى أفكارنا عن الحب والتواصل والعلاقات الجادة والمسئولية وروح الجماعة تنهار في عالم محمل بعبء الحرية اللانهائية في الاختيار وزيادة والسعى نحوالكمال. في حقيقة الأمر التعبير عن النفس يسرق منا ساعات في اختيار الملابس المناسبة وتحديث وتعديل صورة صفحتنا على فيس بوك واختيار الاصدقاء المناسبين للسياق العام. كل هذا التناغم مع أفراد الكون التى بعدت كل البعد عن التفكير والتفكر والمحاولات المستدامة للمشاركة في جهد مشترك مما أفرغ النفس من فحواها تعديل صورة صفحتنا على فيس بوك واختيار الاصدقاء المناسبين للسياق العام. كل هذا التناغم مع أفراد الكون التى بعدت كل البعد عن التفكير والتفكر والمحاولات المستدامة للمشاركة في جهد مشترك مما أفرغ النفس من فحواها”.

Passport, the fallen

Despite traveling most of my life on an Australian passport, I came to write this prose poem as I’ve been moved by the stories and witnessing of countless friends and strangers traveling on less mobile passports and the torment they have had to endure at airports and consulates.

Passport, the Fallen

I never met that medieval Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta, for I would have beset his world travels with heartache crueler than the sea storms that unsettled him,

Known as a travel document, I am more document than travel,

For I am not of the blessed.

They played with my ancestry: I went from world to third-world, developing world, and global south,

As if colourful names ever granted me admission to the geographies of privilege.

I catch a glimpse of my compatriots squeezed between sweaty nervous human hands at passport controls where humanity sheds the pretense of fraternity and re-glues inequalities,

I watch desk officers execute the parochial wave of the times,

A predatory international relations system telescoped into an arbitrary being void of thought,

I am reminded that I have so much power of disdain,

I keep security needlessly occupied and transits an end in themselves,

I make borders out of iron and visas out of alchemy,

I prolong queues into creeping anacondas,

while turning immigration controls into life stations,

Did you know I can unravel life’s plans?

I make families miss their flights,

Laborers forgo their grandmother’s funerals,

Couples reschedule their honeymoons,

Students skip their graduations,

Scholars show up late to conferences,

Journalists lose their story,

Merchants scale back their dreams,

Refugees. Die.

I turn Africa into Alcatraz with no parole,

remake Asia into arcades with no fire exits,

Cast the undesired Americas into an ailment with no remedy,

while watching Europe send her Marco Polo tribes to a playground called Earth.

I dance with fate, whispering in her ear: who can fall in love with whom, who can discover a new realm where, who can seek sanctuary when, who can question their very being and why.

I am the butcher of stories, curiosities, aspirations and encounters.

I am the sorcerer that makes the Indian backpacker invisible,

I am the heirloom of the troubled nation-state, the algebra of colonial logic, the archangel of a geopolitical apartheid,

Bordering. Ordering. Bothering. Othering.

I trigger a silent cry across the planet: “We never asked for this world.”

~Amro Ali (Seville, 16 July 2018)

L’antidoto all’infelicità

An Italian translation of the Mada Masr essay Unhappiness and Mohamed Salah’s Egypt, which featured in Italy’s Internazionale magazine, print edition. (Click here for the PDF magazine version)

“Infelice è la terra che non produce eroi,” esclama Andrea in Vita di Galileo, opera del 1938 del drammaturgo tedesco Bertolt Brecht. E Galileo gli risponde: “No, infelice è la terra che ha bisogno di eroi”.

L’Egitto potrebbe essere quella terra infelice. Un posto dove ormai sono più le feste di addio che quelle di bentornato. Dove una giovane dottoressa medita con tristezza di andare via, perché “far nascere un bambino qui mi sembra moralmente sbagliato, quasi illegale”. Dove il proprietario di un chiosco di succhi di frutta dice con sarcasmo: “Non abbiamo tempo di pensare ad altro che alla sopravvivenza; non abbiamo neanche tempo per pensare al suicidio”. Quando un paese precipita in problemi economici e sociali senza fine e sprofonda nella disperazione, cresce il desiderio di un batal (eroe), una figura che da sola possa comprendere e risolvere la dolorosa complessità del reale.

In Egitto qualcosa ha causato un cortocircuito in uno sport che spesso i governi usano per distrarre le masse. Qualcosa ha intralciato il disegno autoritario che vuole impedire all’unicità di emergere dal lusso della vita egiziana.

Ecco a voi Mohamed Salah, il calciatore, armato della sua etica.

Salah è motivo di speranza per molti, ed è uno spettro inquietante che perseguita le autorità. Perché lui ha davanti a sé delle alternative, ha prestigio internazionale e un’aura di intoccabilità. Poco alla volta è diventato molto di più di un semplice eroe del calcio. Salah è un eroe dirompente, il paradosso vivente di una voce che fa politica senza parlare di politica. La sua è una politica che agisce per giustapposizione inconscia: il calciatore che sembra impeccabile contro i vertici del potere, tanto corrotti e familiari.

Molte personalità egiziane importanti e rispettate sembrano avere una risposta a tutto. Ma poi arriva Salah e ci si trova davanti a domande a cui è difficile rispondere.

Per esempio: perché riponiamo tanta speranza in un uomo?

Salah non può sostituirsi alla politica. Resta pur sempre un calciatore, per quanto bravo. Ma la sua incursione nell’instabile panorama egiziano fa un po’ di luce su quello che è andato storto, e tutto questo entusiasmo per lui pu. dirci qualcosa sull’infelicità egiziana.

Il fatto di restare alla larga dalla politica, o di svelare involontariamente le sue idee, gli ha dato una vasta base di consenso. Dalla rivoluzione del 2011, gli egiziani si ritrovano a vivere tra opposti: rivoluzionario o controrivoluzionario, laico o islamista, civile o militare, liberale o ipernazionalista, pro o contro i Fratelli musulmani. Anche se alcune di queste contrapposizioni si sono placate sotto il regime dei militari, l’unità che si è creata è un’unità in negativo: è quasi sempre contro qualcosa, come il terrorismo; e quando invece è per qualcosa, per esempio per l’Egitto, diventa una costrizione imposta dall’alto, senza spazio per voci o pensieri diversi.

Salah sembra essere il primo, dopo molto tempo, in grado di unire sostenitori e oppositori del regime. Come ha detto un dottorando egiziano che studia in California: “Grazie a Salah sto recuperando il rapporto con il mio paese”.

Qualcosa di peggio

Ormai è normale attribuire l’infelicità in Egitto alla disoccupazione, alla povertà, a un sistema scolastico al collasso, alla censura, alla repressione delle voci indipendenti, alle violazioni dei diritti umani. Indubbiamente questi sono tutti fattori che contribuiscono alla miseria di molti egiziani, ma dietro c’è qualcosa di peggio, di patologico: la triste realtà che all’orizzonte non ci siano alternative. Quella speranza che in passato prometteva che l’infelicità sarebbe stata temporanea si sta affievolendo, e lascia spazio a una tristezza inevitabile. La depressione ti disarma prima ancora che la repressione abbia il tempo d’indossare la sua divisa.

E’ per questo che Salah è come un’improvvisa affermazione di valori umani all’interno di un sistema disumanizzante. Il suo mito non è esploso quando Salah ha contribuito alla vittoria contro il Congo nell’ottobre del 2017 che ha permesso all’Egitto di qualificarsi ai Mondiali di Russia: uno straordinario talento calcistico non basta a convertire i profani del pallone. E non è stata neanche la storia della sua ascesa dalle umili origini alla celebrità. Non c’era nulla di originale in una storia di successo individuale.

Ma poi è venuto fuori l’altro, altrettanto decisivo, aspetto di Salah. Due settimane dopo la partita contro il Congo, l’imprenditore Mamdouh Abbas gli ha offerto in regalo una villa di lusso. Salah ha educatamente rifiutato, suggerendo che una donazione al suo villaggio natale di Nagrig, nella provincia di Gharbia, lo avrebbe reso più felice. Questo gesto, insieme alle sue tante opere di beneficenza, per chi non è tifoso di calcio (come me) è stato a dir poco sconvolgente, e ci ha portati tutti dalla sua parte.

Per capire meglio le implicazioni di un gesto simile, dovete sapere che in Egitto le autostrade sono piene fino alla nausea di manifesti che pubblicizzano gli ultimi esuberanti edifici di lusso e complessi residenziali accessibili solo a chi ci abita. E’ un vero e proprio bombardamento visivo per milioni di egiziani, sconcertati dal fatto che possano esistere progetti simili in un periodo di austerità, in cui viene continuamente chiesto di fare sacrifici. Queste pubblicità, quasi sempre in inglese, e a volte con volti di europei, bianchi e con gli occhi azzurri in primo piano, proclamano a grandi lettere “ E’ il momento di pensare a te”, “Stavolta è una faccenda personale”. Il capitalismo all’ennesima potenza e la speculazione edilizia non solo stanno stravolgendo l’economia del paese, ma stanno anche spingendo al massimo l’individualismo sfrenato, l’avidità e varie forme di disprezzo di se stessi.

Il rifiuto di Salah ha inflitto un duro colpo a una certa cultura del grottesco e dell’eccesso, e ha rappresentato una conferma di quei valori che erano nati (o si erano concretizzati) durante la rivoluzione del 2011, valori che mettevano il bene comune al primo posto. Salah ha infranto una normalità fatta di clientelismo ed espedienti. Se già in molti lo adoravano dopo la vittoria sul Congo, quel gesto e le opere di beneficenza gli hanno fatto ottenere ancora di più il rispetto della gente, anche perché era evidente che non si trattava di una mossa pubblicitaria, ma di un atto coerente con il carattere e la storia del calciatore. L’amore e il rispetto sono due cose diverse.

Da tempo gli egiziani non riescono a guardare qualcuno con rispetto, qualcuno cioè che non sia in esilio, in prigione, o sottoterra. Devono assistere a uno spettacolo estenuante, in cui spesso la versione ufficiale è in conflitto con la realtà e con il senso comune.

Questa guerra di logoramento contro la razionalità ha fatto precipitare gli egiziani in una spirale di conformismo, scetticismo e indifferenza. L’idea di un bene supremo è svanita a poco a poco, mentre il potere ha continuato “non a stimolare la gente con la verità, ma a confortarla con le menzogne”, per dirla con le parole dell’intellettuale ceco Václav Havel. L’intervento di Salah non ha necessariamente cambiato tutto questo, ma ha contribuito a restituire un significato a parole che erano state stravolte: la dignità è tornata a essere dignità, i princípi sono tornati princípi, la generosità è tornata generosità, e la felicità è tornata felicità.

Salah ha toccato anche un’altra questione vitale per lo stato e la società egiziani: il bisogno di un riconoscimento internazionale. Questa necessità s’intreccia con la storia moderna del paese. L’Egitto del presidente Abdel Fattah al Sisi ha fatto innumerevoli sforzi per promuovere la sua immagine, come hanno dimostrato i cartelloni pubblicitari a times Square, a New york, che sponsorizzavano il nuovo canale di Suez con la scritta “Il regalo dell’Egitto al mondo”. Salah è riuscito a impersonare quello slogan in modo molto più dirompente e spettacolare, con un impatto ben più significativo di tutte le campagne turistiche, le conferenze internazionali e tutti i megaprogetti degli ultimi anni messi insieme. Ecco perché nominare Salah in una conversazione può provocare in molti egiziani l’impressione di restare senza fiato, un formicolio alle mani, e un senso di leggerezza.

Questo in parte ha a che fare con la funzione della felicità e del senso della vita. Il regime crede di poter monetizzare la felicità affermando di voler rendere gli egiziani “tra i popoli più felici al mondo”, o discutendo con il ministro della felicità degli Emirati Arabi Uniti sulla possibilità di esportare in Egitto un po’ della loro fantastica pozione.

Sentimenti panarabi

La questione della felicità ha attraversato la storia della filosofia, dall’Etica nicomachea di Aristotele all’Alchimia della felicità di Al Ghazali fino al Crepuscolo degli idoli e all’Anticristo di Nietzsche. Nessuno di questi filosofi avrebbe mai abbracciato l’utilitarismo d’ispirazione anglosassone di John Stuart Mill, che intende la felicità come il massimo utile realizzabile ed è stato riconfezionato dal neoliberismo moderno, rinunciando a una vita ricca di significato di cui la felicità è solo una conseguenza. In altre parole, non si può separare il raggiungimento della felicità dal rispetto per la giustizia, la dignità, la virtù. Eppure le autorità sembrano non mettere a fuoco che la felicità finisce per perdere di senso se non viene salvaguardato l’attivismo dei cittadini, non si apre la sfera pubblica, non si garantiscono processi equi, non s’incoraggia il pluralismo. Se non si evita che il senso dell’esistenza vada in frantumi.

Salah ci lascia sbirciare tra queste fratture, perché comunica non solo più concretamente attraverso il suo successo calcistico, ma anche con l’empatia e la profondità di significato che accompagnano l’onestà del carattere.

La fama di Salah e il suo approccio alla religione arrivano in un momento in cui molti egiziani stanno rimettendo in discussione la loro fede e la loro identità. Quelle norme che un tempo definivano l’osservanza religiosa stanno collassando sotto il peso delle contraddizioni del paese. Lo stato usa la religione per disciplinare in modo arbitrario lo spazio pubblico e i predicatori incoraggiano un islam barocco a discapito dell’essenza umile della religione musulmana.

La diffusa passività spirituale si contrappone alla fede di Salah, che è parte della sua vita pubblica. Anche dopo essere stato catapultato in cima al mondo, non ha mai sentito il bisogno di mettere da parte o modificare la sua identità musulmana. Vedere Magi, la moglie velata di Salah, al suo fianco su un campo di calcio in Europa è stata una scena ipnotica per gli egiziani (e per il resto del mondo), proprio perché è qualcosa d’insolito, soprattutto in un periodo di paure esasperate verso i musulmani in occidente.

Per questi stessi motivi Salah suscita sentimenti di unità in tutto il mondo arabo e musulmano. Ha fatto la sua comparsa sulla scena dei writer libanesi e nelle schede elettorali annullate per protesta in Libano (proprio come in Egitto), ha scatenato una bizzarra manifestazione pacifica fuori dall’ambasciata spagnola a Jakarta dopo il fallo che ha subíto da Sergio Ramos. L’immagine, un tempo diffusa nel mondo arabo, di un Egitto, forte, vivace, nobile, con un ruolo di guida e aperto al mondo – un paese che promuove le arti, dimora del pensiero sunnita, fautore del panarabismo e difensore della causa palestinese – oggi viene proiettata su Salah. Quando s’inginocchia sull’erba e alza gli indici al cielo, centinaia di milioni di musulmani sono attratti da una devozione che è familiare ma che va oltre la cultura e la religione. Mentre il mondo occidentale sprofonda nella sterilità neoliberista, nel consumismo, nella solitudine, negli scandali, nel populismo, nella xenofobia contro i rifugiati e i migranti, nell’islamofobia, nell’antisemitismo e nelle notizie false, il Salah poliedrico (calciatore, padre amoroso che gioca con la figlia) si staglia come un momento di verità e di universalità.

L’alternativa possibile

Albert Camus, immaginando di rivolgersi a un destinatario tedesco, nel 1943 scriveva: “Io vorrei poter amare il mio paese pur amando allo stesso tempo la giustizia. Non voglio per lui alcuna grandezza, soprattutto non una grandezza fatta di sangue e di menzogna. E’ facendo vivere la giustizia che voglio far vivere il mio paese”.

Forse Salah incarna questo ideale: l’amore per un paese non chiede grandi cerimonie o di battersi il petto, ma vuole bellezza, sincerità, umiltà e benevolenza. In un panorama senza modelli degni di rispetto, Salah ricorda agli egiziani che esiste una natura umana migliore. Per l’Egitto e per il resto del mondo l’anomalia Salah mostra che l’alternativa al nazionalismo non è il tradimento ma la responsabilità civica, l’alternativa al conservatorismo non deve essere per forza l’apatia o lo scherno verso il sacro, e l’alternativa all’ingiustizia può essere il perdono. In fondo, in molti avevano quasi dimenticato come le celebrità potessero essere umili.

Salah è quella rara festa di bentornato che gli egiziani aspettano da tempo. Il suo volto sulle lanterne illumina i vicoli bui, i suoi poster colorati coprono i manifesti elettorali sbiaditi.

Anche se è chiaro che Salah non potrà influenzare la situazione politica in Egitto, la sua esistenza vivace indica degli spiragli per il ritorno a una sfera di autenticità. Salah espande l’immaginario etico di un pubblico vigile, mostra delle possibilità, lasciando intuire che il ritmo della vita è qualcosa di più delle nascite, dei matrimoni, delle morti, e perfino dello sport.

E solleva una domanda, con cui prima o poi i potenti dovranno fare i conti, perché ci sono delle ragioni se le persone hanno bisogno degli eroi: cosa avete fatto per renderle così infelici?

Denmark is Entering Frightening New Territory with “Ghetto” Policies

Published in TIME magazine

At the blazing apogee of the Second World War, a poignant essay on the embattled life of refugees and immigrants was published in an obscure 1943 journal. Written by Hannah Arendt, the German-Jewish philosopher and political theorist, and, by then, embittered refugee, the essay closed with the words: “The comity of European peoples went to pieces when, and because, it allowed its weakest member to be excluded and persecuted.”

Arendt’s message was soberingly simple: Targeting a vulnerable group is the start of unraveling processes that bring greater and far-reaching ruin.

This year, Denmark’s xenophobia and move to the right has entered frighteningly new territory to supposedly prevent immigrants forming a “parallel society.” Let’s not forget that Denmark already has the Bohemian autonomous Christiania—which has caused decades of headaches for the Danish government but whose inhabitants are still less stigmatized than immigrants.

Among the many changes, children from “ghetto” areas—where more than 50% of the population are non-Western immigrants, mainly Muslims—will have to attend obligatory daycare for 25 hours or more a week from the age of 1, so that they learn “Danish values” and traditions, like Christmas and Easter. A law under consideration would impose a four-year prison sentence for parents who commit “re-education trips”—sending their children on “extended” visits to the parent’s country of origin.

The legislation reads like a 19th century missionary enterprise, a colonial experiment to civilize the brown folks.

The peril is that this form of divisive politics will seep deeper into the tapestry of the illiberal anti-immigrant pan-European movement. Denmark is not just setting a precedent; it is sparking a game of one-upmanship in the performance of transnational bigotry.

If immigrants fully “assimilated” or vanished from the land, then the logic might follow the xenophobic movements would close shop and populist parties would scale back their rhetoric and shift policies to mundane domestic affairs. That rarely happens.

Such movements and parties stake their existential politics on discriminatory and exclusionary practices (despite the claim of inclusionary intentions of wanting to assimilate the immigrants) which are then further reignited along election cycles. Unabashed political interests, not humane social policy, is what matters to them.

As soon as the initial victims are exhausted, new targets are sought out. Hatred and fear never operate within rational boundaries. It’s all-pervasive; passions take over level-headed policy deliberation—not surprising, the Danish government did not involve experts, researchers and residents in the discussions. It echoes Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism: “For the only thing that counts in a movement is precisely that it keeps itself in constant movement.”

Prior to Britain’s 2016, referendum on membership of the E.U., some in the pro-Brexit campaign focused on trying to end Muslim immigration. But quickly after Britain voted to leave, racial vilification and attacks quickly spread to target Poles, Latvians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Jews and, perhaps the least expected, the Swedes.

Norway-based Muslim intellectual, Iyad el-Baghdadi, points out that “minorities are the canaries in the coal mine.” The state of their well-being, fear, anxiety, flight, is a bellwether of their overall society—whether it be Muslims in Europe, Christians in the Middle East, Shiites in Saudi Arabia, Kurds in Turkey, Baha’is in Iran, Hindus in Pakistan, or African-Americans in the United States. When the toxic gas of populist exclusion is diffused through society, the minority is the first to succumb to it. However, others soon follow. Fractures appear in dominant groups, and the fabric can go to pieces.

Denmark’s policies should make us all wary. This idea of cleansing society of immigrants marks the dismantling of higher ideals, pluralist values, and ethical standards. The mishandling of the “ghetto” question may just be the embryonic stage of a bigger ominous current yet to come—one that could make Muslims and non-whites the least of Denmark’s perceived problems.

Unhappiness and Mohamed Salah’s Egypt

Published in Mada Masr, republished in openDemocracy, and Internazionale (Italian print edition)

“Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero,” Andrea cries in the 1938 play, Life of Galileo, by German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, to which Galileo responds: “No, unhappy is the land that needs a hero.”

Egypt can be that unhappy land, a land where farewell parties have outstripped homecoming parties. Where a young female doctor laments she wants to leave because “to give birth to a baby here feels morally wrong, it feels sort of illegal.” Where a juice seller sarcastically quips, “We no longer have time to think of anything else but survival, we don’t even have time to contemplate suicide.” When a country is mired in endless social and economic problems, and smothered in despair, the yearning grows for that batal (hero), that one human figure where all painful and complex abstracts will be realised within and resolved without.

Something happened in Egypt that short-circuited a sport that is often treated by governments of all persuasions as a distracting bread and circus for the masses. Something interrupted the despotic drive to stamp out the uniqueness from the flow of Egyptian life.

Enter Mohamed Salah armed with a moral code.

While Salah is seen to bring hope to many, he is an unsettling spectre that silently haunts the establishment, for he has options, international prestige and the perception of untouchability. He has grown to be more than a hero of football success. Salah is a different sort of hero, he is a hero of disruption, and a living paradox of a political voice without talking politics. Salah operates in a politics of juxtaposition in which his perceived immaculate persona is unconsciously contrasted with the familiar polluted forces of high politics.

While many of Egypt’s prominent and established figures seem to have an answer for everything, Salah shows up and we’re faced with difficult questions. Namely, why are we investing so much hope in one man? This is more than about the World Cup.

Salah is not a substitute for viable high politics. He is, after all, a football player, and a very good one at that, but his insertion into the volatile Egyptian climate sheds some light on what has gone wrong and why the current fervor around him can illuminate the question of Egyptian unhappiness.

Salah’s stance to steer away from politics, or from inadvertently disclosing his political leanings, has given him an amplified united base. Since the 2011 revolution, Egyptians have had to live with binaries: revolutionary versus counter-revolutionary, secular versus Islamist, civilian versus military, liberal versus hyper-nationalist, pro and anti-Brotherhood, among others. While many of these binaries have diminished under the shadow of the generals, the unity that has come in its place is a negative unity. It is almost always against something, such as terrorism, and when it stands for something, let’s say Egypt, it’s a nationalist straightjacket that is imposed, with no room for plurality of thought or voices.

Salah might just be the first figure in a while behind which pro- and anti-regime supporters can unite. In the words of an Egyptian doctoral candidate studying in California, “Salah is the reason I’m mending my relationship with Egypt.”

It has become commonplace to argue that unhappiness in Egypt is caused by high unemployment, poverty, dysfunctional education, censorship, a crackdown on independent voices, and overall human rights abuses. While there is no doubt these factors contribute to the misery of many Egyptians, there is something worse and pathological that lurks behind them all: The grim reality that new possibilities no longer emerge on the horizon. The dilution of hope that once offered the promise that unhappiness was a temporary moment, now feels for many like the ink of sadness has dried. Depression disarms you before repression even has time to put on its uniform.

For this reason, Salah is like a sudden assertion of human values within a dehumanising system. This did not arise when Salah helped defeat Congo, propelling Egypt into the World Cup last October. Astonishing football talent is not always enough to convert non-football watchers. Nor did his story of humble beginnings to stardom take hold in this moment. There was nothing original in any of these individual success stories. Perhaps because they remained just that: individual.

But then came the other, and equally decisive, side of Salah. Barely two weeks after this victory, and because of it, Salah was offered a luxury villa by entrepreneur Mamdouh Abbas. He politely declined the gift and suggested that a donation to his village Nagrig in Gharbia would make him happier. This move, along with many of his charitable acts, for non-football fans, including myself, was thunderous to say the least, and swayed us to his camp.

To put the implications of this act in a wider context: Cairo’s highways are nauseatingly choked with billboards flaunting the latest exuberant luxury real estate and gated compounds. It is an assault on the senses of millions of Egyptians who are puzzled as to how such developments take place in an era of painful austerity measures, in which they are being asked to continually sacrifice. The billboards, almost always in English and at times with white, blue-eyed European faces, loudly proclaim, “It’s time to think about you,” and, “This time it’s personal.” It is not enough that Egypt’s capitalism on crack and real estate speculation is skewing the economy, but it also ramps up hyper-individualism, greed, and various strands of self-hatred.

Salah’s rejection of the villa was a violent piercing into a culture of the grotesque and excessive, and signified his upholding of the values born, or crystallized, during the 2011 revolution that put the common good above all. His refusal was a significant breach in the business-as-usual patronage and wheeling and dealing circles. If Salah was loved for his victory over Congo, he was now respected more for this move and the many charitable stories that emerged, making it obvious that this has been his character for a long time, and that he didn’t reinvent himself for PR purposes. Love and respect are two different beasts. Egyptians have long missed looking up to someone who commands respect, at least someone who is not in exile, in prison, or long dead.

In recent years, Egyptians have had to live with the exhausting spectacle of doublespeak in which official interpretations are often in conflict with lived realities and common sense. The train heading to Alexandria is declared to be on its way to Aswan, as veteran journalist Yosri Fouda once put it. This war of attrition on rationality has plunged Egyptians deep into a spiral of conformity, scepticism and indifference toward each other. The idea of the higher good receded as officialdom continued, in Czech philosopher Václav Havel’s words, “not to excite people with the truth, but to reassure them with lies.” The intervention of Salah did not necessarily change all that, nor did it reverse the Orwellian trend, but he did help restore meaning to terms that had become scrambled: dignity became dignity again, principles became principles, kindness became kindness, and happiness became happiness.

Salah touched on another existential question within Egyptian state and society: the strong desire for international recognition. This phenomenon weaves its way through Egypt’s modern history. There have been concerted efforts to export Sisi’s branded Egypt, for example, with the new Suez Canal project billboards dotting New York’s Times Square with the slogan “Egypt’s gift to the world.” Salah, instead, lived up to fulfilling that slogan in a much more dramatic and compelling way. In fact, Salah has arguably had more impact on the world’s positive views of Egypt than all the recent years of tourist campaigns, international conferences and mega projects combined. In light of this, mentioning Salah in conversation can give many Egyptians a feeling of breathlessness, tingling hands and a sensation of weightlessness.

This in part has to do with the function of happiness and meaning. If the regime is not suffering from cherophobia (fear of happiness), it believes it can commodify happiness by stating it intends to make “Egyptians among the world’s happiest,” or through the recent discussions with the UAE’s Ministry of Happiness to “export” some of their cool psychedelic juice to Egypt.

Happiness is a question that spans a history of philosophical musings, from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, to Al-Ghazali’s Alchemy of Happiness, to Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols and the Antichrist. All of them would shun the Anglo-inspired utilitarianism of John Stuart Mills that speaks of happiness as the ultimate net objective and has been largely repackaged for neoliberal modernity, rather than a meaningful higher life that produces happiness as a by-product. In other words, you cannot separate the attainment of happiness from respect for justice, dignity, honour, etc. It doesn’t seem to phase the authorities that happiness is meaningless without rescuing vibrant citizenship, opening public spaces, providing fair trials, encouraging pluralism, and preventing overall existential meaning from being fragmented.

Salah offers glimpses into the voids spawned by the above fractures as he communicates not only on the instrumental level of football success, but with meaningful and empathic qualities that come with an honourable character. It is no wonder that Salah was able to inspire calls to a drug user helpline to shoot up by 400 percent.

Salah’s fame, coupled with his stance on religion, comes interestingly at a time when many Egyptians are renegotiating their faith, identity markers and boundaries. The norms of what once constituted a religious person are breaking down under the weight of the country’s endless contradictions. All this takes place beneath the purview of a state that uses religion to arbitrarily police the public space, and preachers who continue to push a baroque Islam at the expense of the religion’s humble essence.

The rise of a widespread spiritual passivity contrasts with Salah’s faith, which has come to animate his public life. He saw no need to dismiss or distil his Muslim identity, even after he achieved a turbo-charged social mobility and stardom. This is not lost on many. The sight of Salah’s veiled wife, Maggie, by his side on a green oval in a European city before the eyes of millions, is a hypnotic sight to Egyptians (and the rest of the world) precisely because it is unusual, particularly at a time of heightened anxieties toward Muslims in the West. “I respect him as he is not embarrassed nor does he try to hide his veiled wife after all that success,” an Alexandrian barber says.

It is for the same reasons that Salah can sprout pan-Arab and pan-Islamic wings across the Arab and Muslim world. He has made it into Lebanon’s graffiti scene and protest ballots in the Lebanese elections (just like Egypt) to a bizarre planned peaceful protest outside the Spanish embassy in Jakarta after the injurious tackle by Sergio Ramos. The Arab world’s traditional idea of a leading, strong, vibrant, noble and outward-looking Egypt – one that spearheads the arts, preserves the seat of intellectual Sunnism, champions pan-Arabism, and stands up for the Palestinian cause – is projected onto Salah with deafening force. Between prostrating on the grass and raising his index fingers to the heavens, hundreds of millions of Muslims are drawn to this well-understood language of piety.

But this attraction transcends culture and religion. As the western world is bogged down in neoliberal sterility, rampant consumerism, loneliness, high-level scandals, populism, xenophobia against refugees and immigrants, anti-Muslim bigotry, anti-Semitism and fake news, the multi-layered Salah – the intimately relatable footballer and loving father who kicks a ball with his daughter Makka – stands out like a moment of truth and living universality, with a mammoth mural recently going up in Times Square reflecting his larger than life image.

Albert Camus wrote to an estranged German friend in 1943: “I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice. I don’t want any greatness for it, particularly a greatness born of blood and falsehood. I want to keep it alive by keeping justice alive.”

Salah perhaps embodies this ideal. That love of country does not require drums and chest-beating, but grace, sincerity, modesty and charity. He is a reminder to Egyptians that there exists a better human nature in a landscape barren of prominent reverential role-models. To Egypt and even the rest of the world, Salah is the outlier that proclaims the alternative to nationalism is not treachery but civic responsibility, the alternative to stifling religious conservatism does not always have to be apathy or mockery of the sacred, but breathing faith into a sound value system, and the alternative to injustice can be forgiveness. Ultimately, people had almost forgotten what humility among those with renown looks like. Particularly, a humility that is relentless and consistent, despite being trialled under the stadium floodlights and the stars sprinkled across the Liverpool night sky.

Salah is the rare homecoming party Egyptians have long awaited. His face on dangling lanterns lights up dark alleyways, and his colourful posters germinate over the debris of fading election posters in a country that sees official and media-manufactured heroes reckon with publicly-anointed heroes.

While it cannot be implied nor expected that Salah could impact the political situation in Egypt, his animated existence spotlights entry points back into the realm of authenticity. He widens the moral imagination of an attentive public and parades the possibilities that infer that the rhythm of life involves more than birth, marriage, death and even sports. He also raises questions that many power-holders will have to grapple with eventually, someday: That, above all, there are reasons why people ache for heroes in the first place. — What have you done to make them this unhappy?