A zoom lecture on approaching an MA and PhD for students at the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo (a repeat public lecture coming soon).

Author: Amro Ali

Paranormal Activity: Inside Netflix’s First Egyptian Arabic Original

Published in GQ Magazine

In 1993, Ahmed Khaled Tawfik began a series of sci-fi horror books that would change the lives of millions in the Middle East. Now translated into a new Netflix series, Paranormal is set to bring Egyptian storytelling to the world

Ahmed Khaled Tawfik knew that it would happen after his death. The big fame, that is, the fame that translated from 15 million copies shifted of 81 best-selling novels in a genre that was quite frankly non-existent in the Middle East up until he and his work arrived. Now, as Netflix prepares to drop Paranormal (you’ll likely know it better as Ma Waraa al-Tabeea), a series based on his revolutionary sci-fi horror novels, you get the impression that he might just have been right.

It may seem ironic that a region with more than its fair share of real-world horror is so lacking in the storytelling genre, but that’s not because the stories would be hard-pressed to keep up with the news. Chalk it up instead to misunderstanding. Analysts would often ask the late Egyptian novelist why Arab youth resorted to reading his gothic horror stories if their own lives were already steeped in pain, anxiety and uncertainty? Exactly what type of escapism could books like these possibly provide? Tawfik knew only too well.

“The idea of reading horror is that you approach death without dying.”

“Horror provides a nominal escape from your problems because, no matter how bad your life is, the horror story can show us that it could be much worse,” he once said. “The idea of reading horror is that you approach death without dying.”

Tawfik’s enormous readership and success with the pocket novel series featuring the cynical, dark-humoured Dr Refaat Ismail was proof positive that it was exactly what the region was looking for. And the character’s resurrection via Netflix is set to be nothing short of groundbreaking – in more ways than one.

The production has attracted award-winning heavyweights. Paranormal is directed and produced by Amr Salama (Sheikh Jackson, Excuse My French, Asmaa), and co-produced by Mohamed Hefzy (Clash, Yomeddine, You Will Die at Twenty). It’s the third Arabic and the first Egyptian Netflix Original production and, as Ahmed Amin, who plays Dr Ismail, rightly exclaims, “The series will hopefully open a window to the world and exclaim that there is an original and influential horror genre happening in Egypt.”

For those who have never touched the books: Ismail is an aging haematologist who encounters a world where logic and scientific reason are replaced with local mythology and global folk tales. Ismail takes on a “journey of doubt” – battling numerous health problems with a ready supply of medicines rattling in his pockets as he goes. He is an anti-hero so ordinary and frail that he came to be loved. Unlike previous heroes in Arabic literature, Ismail mirrored the torrent of failings and contradictions in Arab societies. Regional publication ArabLit painted him as a breakaway from “the squeaky clean image of the hero in Arabic writing”. Arabic folklore has usually favoured “knights on horseback” and moral absolutisms. Ismail was plain, yet imaginative enough to draw the reader into his animated world. This meant something to the young people in Mubarak’s Egypt, where you could argue imagination was overshadowed by a prevailing zeitgeist of mediocrity.

The show’s director and executive producer, Amr Salama, has waited years to realise his vision

It pays to be clear. Perhaps no Arab author has been as underrated as Tawfik. Born in the Egyptian city of Tanta in 1962, he became a physician and professor of tropical medicines at Tanta University, eventually diverting a slice of his attention to fiction writing. “My English was not yet good enough to read horror literature, so I started writing it myself,” he once said. Cut-off from the literary influences of the English-dominated fiction book market – and with Arabic horror novels non-existent – he began to construct his own world based around the turbulent experiences of Egyptian life. “If I had read Howard Phillips Lovecraft, Stephen King, [and Mary Shelley], I would never have written,” he said. “I would have just been satisfied with what I was reading.” But there was influence there. Only rather than Anglo-fiction, it ended up being the works of Anton Chekhov, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy that would silently mentor him.

If you would really like to see a measure of what young people in Egypt thought of Tawfik, you need only to look at his death in 2018. Attracting thousands of young mourners to his funeral, the footage sent shockwaves through the Cairo establishment, bewildered at how a dead novelist who they had barely registered as a legitimate cultural influence could so effortlessly draw more Egyptian youth than an election.

In the early 1990s, a young Amr Salama went hunting for a book that came from Egypt – any book – at the one store he frequented while growing up in Saudi Arabia. He stumbled upon a section titled “Egyptian Pocketbook Novels” and it filled him with excitement, addressing the void in a boy longing for his home in Cairo. His purchase was from the Paranormal series – the first books he would ever read outside of his school curriculum – and they would stay with him for life. Years later in 2006, while still a budding director, Salama contacted Tawfik with an idea to turn Paranormal into a TV series. They struck a warm, long friendship. “He was like a father to me,” Salama would later say.

Bit by bit, the pair made plans both precise and ambitious, building a vision that would not be compromised. One of the agreements: they would not straitjacket the novels to fit the 30-day Ramadan series schedule – a time when television in the Arab world is sacred. “Not doing the 30 Ramadan episodes allowed for a certain slowness and quality,” says Majid Al Ansari, the second block director for the series. And that liberation is quite telling. The first scripts appeared in 2006 and have been reviewed word-by-word on a regular basis ever since. Filming was undertaken in sections to foster synchroneity and flow, and authenticity was demanded in everything. Salama did not want to rely on tropes imported from abroad. “We want to give an Egyptian voice and sound it to the world,” he says.

Nothing was spared when it came to remaining true to the story. Even though the Abu Rehab palace, located in Cairo’s El Manial district, was constructed in the 1940s, production designer Ali Hossam felt that they needed to bring it in tune with the villa in the novels that was built in 1880. And that included efforts to give it a rural grassy surrounding to mimic the belle époque villas and mansions that once stood in Nile Delta cities like Mansoura in the colonial era.

Walking through the house early in the production, it’s clear that the set designs were thoroughly considered to meet the exacting standards of not only Netflix, but Salama – and indeed, the late Tawfik – too. After all, this is meant to be a haunted house, so there’s an abundance of dust, chandeliers with broken strings of crystals, peeling wallpaper, torn curtains, old portraits, gloomy staircases, and a wealth of cobwebs all over. It dawns on me that most Egyptian homes, if left unattended for a few years, actually look somewhat like this. Elsewhere, the special effects and makeup team, Donia Sedky and Eslam Alex, explain the steps of transforming a child actor into a hideous demonic character (apparently the children have more patience and stamina for this laborious process than adults).

Amin says that he is confident that audiences will come to see a series that was made with “sincerity, detailed attention, and responsibility” – and that Tawfik’s world of Cairo in 1969 is captured in piercing detail. It reflects the mood of a public that had long outgrown political rallies and anti-colonial exhilaration and now walked despondently in the shadow of Nasser’s Egypt. Reeling from defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War, there was an ambivalence with the quasi-socialist experiment and a shattering of pan-Arabist dreams, only to perhaps find comfort in the inordinate amount of trees lining the streets. This is a long-forgotten version of Egypt that operated in a poetically slow mode: from the Cadillacs to the iconic black and white Fiat taxis roaming in second or third gear. High pressure capitalism was yet to make its mark in Cairo and life was set at a much more gradual pace.

Lebanese-British actress Razane Jammal – whose previous projects are as varied as Djinn and Kanye West’s Cruel Summer – plays scientist Maggie McKillop

Salama admits that capturing the true essence of the book’s various time periods was a sizeable challenge. “The more you went back in time, the more difficult it was to portray the details.” While 1969 might have been relatively easy to establish costume, casting, and setting, 1941 was much more difficult, and 1910 even more so.

There was also initial controversy surrounding the casting of Amin in the starring role as Ismail, largely due to the actor’s longstanding association with comedy. Just how could the man that made his name in 30-second viral videos on Facebook play the austere and introspective Ismail? Thankfully, it turns out that Amin had long been a fan of the series, and is well-read on Tawfik’s other works too. As a result, he was able to create a multi-dimensional, compelling character that even the most ardent of Tawfik’s fans will likely appreciate. And while Salama naturally took some creative licence in adapting Paranormal to the screen, it was done with Tawfik’s blessing and is largely faithful to the spirit of the novel.

The series raises broader questions, too, about just how this project can resonate in the current climate of entertainment saturation. While lockdown has amplified our reliance on streaming services, it’s a trend that has been gaining momentum for years. Popular culture that was once drip fed to us over weeks is now drilled straight into our veins. “Before the pandemic I would watch a season per month,” admits Salama. “Now I watch a season per day, and if you asked me what I watched yesterday I wouldn’t even remember. The side effect now could be that one show gets talked about for two days instead of a month.”

“If we achieve this, it will be a breakthrough for Egypt and the Arab world. It will raise the standard of what we can provide for the world.”

Amin’s casting has raised eyebrows, but he’s long been a fan of the series

Amin’s casting has raised eyebrows, but he’s long been a fan of the series

But Paranormal is highly unlikely to suffer a fate of irrelevance, given it can count on a large fan base that has steadily grown since the early ’90s. It has influenced multiple generations of readers, producing a readymade demographic built on a love of literary quality and the essence of a sublime, horrifying story. The team stress that this is what they are taking to the Netflix table. “Human values are quite consistent when it comes to the idea of a good story,” says Amin. “People love a good storyteller, and in a beautiful tale there are meanings connected to the human being in every place – irrespective of geography and language.” As a result, they hope the project will be a watershed moment for the region, offering mass exposure to Middle Eastern storytelling in much the same way that Money Heist shone a light on talent from Spain. “If we achieve this, it will be a breakthrough for Egypt and the Arab world,” says Salama. “It will raise the standard of what we can provide for the world.” Aya Samaha, who plays Ismail’s embittered fiancée Huwaida, argues that the screen version has a longevity and even stronger effect than the book, enabling it to provide a holistic picture. “We are in a win-win situation, as the novels are already a success, and the fans are everywhere. But now they will see it as a clearer picture. If we give it depth and detail it will complement the longevity of the novels themselves.”

On a TV programme in 2014, viewers were invited to call in and ask questions of that episode’s guest, Ahmed Khaled Tawfik. One of the callers was Salama, who delivered a touching message to his friend. “I want you to know that as long as I live, I promise I will fight until Paranormal comes to light in the best shape and best quality to be competitive on the global stage,” he said. Later conversations between the pair would see Tawfik explain his regret that he may never see the day Salama’s promise came true.

But success for Paranormal is about more than mere posthumous fame. While only one of Tawfik’s books has so far been translated into another language (Utopia, 2008), Salama believes that this great eulogy via Netflix could be the moment that changes everything. The moment that Middle Eastern stories are told to the world, and the moment that Dr Refaat Ismail once more comes to life. Tawfik, you know, would have heartily approved.

Paranormal releases on Netflix on November 5.

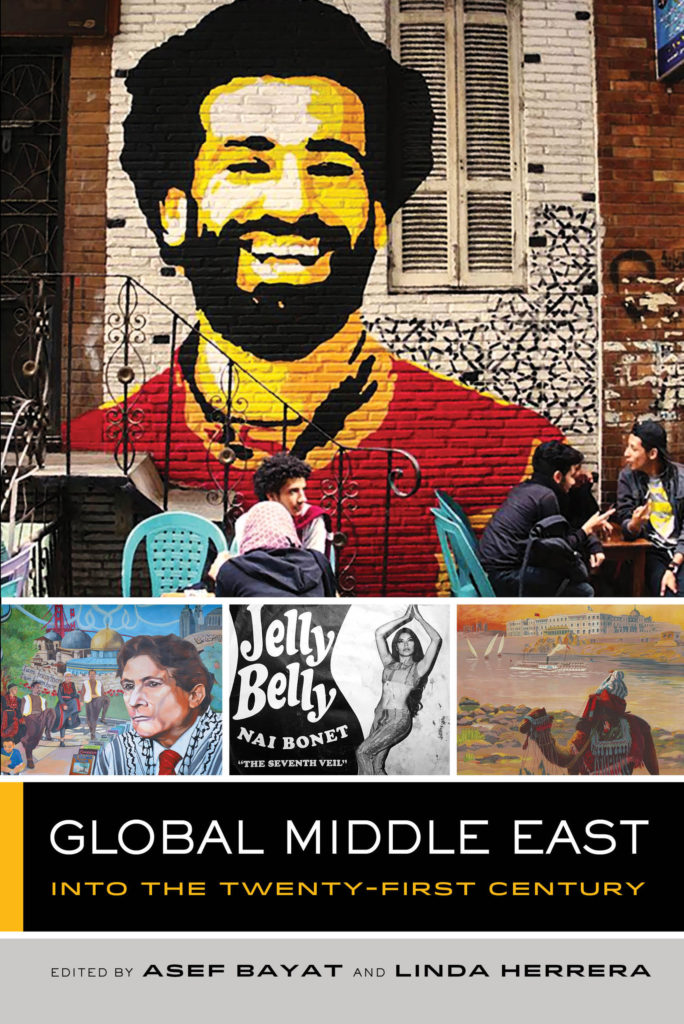

Global Middle East: Into the Twenty-First Century

The edited book, Global Middle East: Into the Twenty-First Century, by Asef Bayat and Linda Herrera, is out now with the University of California Press. I have a chapter that explores the positioning of Mohammed Salah and moral codes within Egypt, the Middle East, and the world. I’m honoured to be with such a great lineup of names.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Localities, countries, and regions develop through complex interactions with others. This volume highlights the global interconnectedness of the Middle East—both ‘global-in’ and ‘global-out’. It delves into the region’s scientific, artistic, economic, political, religious, and intellectual formations and traces how they have taken shape through a dynamic set of encounters and exchanges.

Written in short and accessible essays by prominent experts on the region, the volume covers topics ranging from God to Rumi, food, film, fashion, and music, sports and science, to the flow of people, goods and ideas. It tackles social and political movements from human rights, Salafism and cosmopolitanism, to radicalism and revolutions. Students will glean new and innovative perspectives about the region using the insights of global studies.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Preface

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

Global Middle East – Asef Bayat and Linda Herrera

PART TWO – NATIONS WITHOUT BORDERS

God – Ebrahim Moosa

Algebra, Alchemy, Astronomy – Robert Morrison

Rumi, the Bridge Builder – Fatemeh Keshavarz

On Nations without Borders – Hamid Dabashi

PART THREE: HOME AND THE WORLD

Reflections on Exile – Edward Said

Mo Salah, a Moral Somebody? – Amro Ali

Gamal Abdel Nasser – Khaled Fahmy

PART FOUR: FOOD, FILM, FASHION, MUSIC

Circuits of Food and Cuisine – Sami Zubaida

Pictures in Motion – Kamran Rastegar

Musical Journeys – Michael Frishkopf

The Kufiya – Ted Swedenburg

PART FIVE – GEOPOLITICS OF GOODS

Water of Vulnerability – Jeannie Sowers

Cycle of Oil and Arms – Timothy Mitchell

Cotton, Made in Egypt – Ahmad Shokr

Ports of the Persian Gulf – Laleh Khalili

PART SIX: HUMAN FLOWS

Touring Exotic Lands – Waleed Hazbun

Outsiders of the Oil States – Ahmed Kanna

The Levant in Latin America – John Tofik Karam

PART SEVEN: POLITICS AND MOVEMENTS

Global Tahrir – Asef Bayat

Islamizing Radicalism – Olivier Roy

Global Movement for Palestine – Ilana Feldman

Human Rights, Indigenous and Imperial – Lori Allen

Cosmopolitan Middle East? An Interview with Seyla Benhabib – Linda Herrera

Contributors

Index

Coronavirus Warning Apps (podcast)

“In this podcast episode, AGYA member Dr. Amro Ali from Egypt and AGYA alumnus Dr. Kalman Graffi from Germany discuss Coronavirus warning apps, delving into their advantages, disadvantages and effectiveness from both a technological and ethical point of view.”

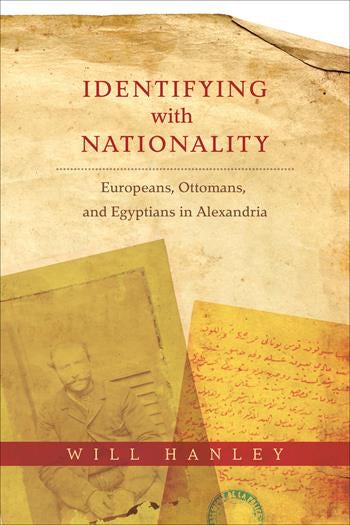

(Book Review) Will Hanley, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria (2017)

My book review of Will Hanley’s work “Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria” has been published in the Mashriq & Mahjar journal (Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies, North Carolina State University). The PDF article is open access.

REVIEWED BY AMRO ALI, American University in Cairo

“Who are you?” is an all too familiar question in everyday life, one that is neither bound by time nor place, but can carry extraordinary consequences for the person being asked, and for history itself. It is a question that is central to Will Hanley’s outstanding book, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria, which illuminates Alexandria as a key sociolegal laboratory in the making of our modern world, covering the decades between the early 1880s and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. In this short pivotal span of history, Hanley telescopes into an enriching fusion of people from different countries who crossed each other’s paths on the streets, sidewalks, trams, trains, cafés, restaurants, and theatres. For many, the idea of personal identity revolved around timeless identifiers such as birthplace, religion, and marital status. They also had a nationality label but this, particularly until the 1880s, was usually a dormant, if not meaningless, category. That is, nationality suddenly meant everything when it became both a formal and informal requirement by the authorities or offered social and legal advantages.[1] That realization would bring people, and hence cement their cases on paper, to the police stations, consulates, and courts of Alexandria. The “wrong” nationality, like a Cypriot, could be a burden on the individual, while a privileged nationality, such as French or British, could mean protection from prison and access to wealth.[2] Egyptians, for whom the idea of nationality was yet to gain any social and legal coherence, were disgruntled at the nationality scourge that not only disadvantaged them compared to other nationalities, but the questionable court sentences and dubious acquittals also served to prove that the “outward garment of nationality concealed the domestication of the rule of difference.”[3]

Hanley’s book is divided into three parts, containing twelve chapters, an introduction, and an epilogue. In section one, “Settings,” Hanley illustrates the organizing concept of “vulgar cosmopolitanism” in chapter one. This concept drives the book’s key theme that shifts our familiar notion of Alexandria from a romanticized understanding and elite-centered cosmopolitanism to the mundane everyday life of Alexandria. The latter is where the matrix of passing, ignoring, jostling, and arguing occurs with habitual frequency until it crosses into legal territory, such as breaking the law, often lubricated by liquor and fomented by misunderstanding. Chapter two fleshes out keywords: national, citizen, resident, foreigner, and subject. The chapter aims to map out the book’s conceptual topology and the placement of individuals and their identities in the making of the emerging world at the turn of the twentieth-century.

In the second section, “Means,” Hanley scrutinizes the mediums of identification in the daily lives of society through the chapters of —“Papers,” “Census,” “Money,” and “Marriage” — which taught the population to identify with new labeling practices and familiarize themselves with a new vocabulary. The chapter “Papers” explores how passports and identification documents became the portable and impersonal means for the authorities to manage the mobility of individuals. While the chapter “Census” looks at the product of the state’s appetite to amplify its state-building project, negotiate disputes with diplomatic authorities over nationalities, and centralize the certification of identity. [4] The chapter on money fleshes out how currency became symbols for the emerging political and economic order and, hence, it required that tokens be honored. In light of this, counterfeiting was seen as an egregious crime, as it challenged the official order and the state’s power to circulate and monopolize symbols of value. The standardization of currency and material advantages sharpened the ability for nationalities to gain access to benefits and favorable rulings from judicial institutions that were predisposed towards wealthy national communities. [5] Finally, the last chapter of the section, “Marriage,” was a site of administrative anxiety given that nationality was largely a gendered practice by how easy it was for women to switch to their husband’s nationality or retain their father’s nationality through marriage, remarriage, separation, or divorce. But their transition depended upon the usefulness of the nationality in question, thus making marriage the “driving wheel of nationality litigation and legislation.” [6]

Hanley’s third section, “Other Nationalities,” spans six chapters: “Europeans,” “Foreigners,” “Protégés,” “Bad subjects,” “Ottomans,” and “Locals,” which takes up the larger essence of the book, as it seeks to map out the triumph of the nationality category, even with its precarities, over other markers of identification. Yet, Hanley takes us into a more complicated field beyond “powerful” Europeans and “weak” natives, as colonial privilege could not be easily deployed as distinctions were rarely obvious. For example, outside the small circles of European notables whom clearly had brazen privilege, poorer Europeans found themselves constrained by class, race, or gender.[7] Similarly, non-European foreigners like Tunisians and Maltese, who were imperial subjects, could exercise benefits in Egypt that were not possible back in their home country.

The case against Alexandrian cosmopolitanism that privileges elites and pioneers is certainly not new and has been fashionable in academic circles for many years. The author, however, gives the subject matter justice as he makes a strong case for shifting from the elites and small literary circles that intended to leave a legacy of written accounts, to the ordinary Alexandrians who did not. Thus, the book’s outcome is a one-by-one pointillist tapestry that draws you into a different Alexandria. Hanley argues against the proponents of triumphalist histories, writing, “We are not obliged to grant the nation the epic imaginary proportions,” and in making the case for the everyday ordinary, ironically, gives his work a distinguished epic of its own.[8] All accounts ended up in court and consulate documents, much like the recorded banal exchange between two Maltese friends, reading, “Today is Saturday, let us go and have a walk,” and ends with one friend fatally stabbing the other. [9] The dizzying number of accounts reads like miniature dramas with an endless cast of actors straddling the turn of the century, dazzling the city, and animating the era in fascinating ways. Taking the stage is the Cypriot realizing his Ottoman-ruled origins offered no protection from torture in a police station; the Egyptian woman who fell in love with an Italian man causing a scandal; the British consular official rushing to stop a marriage between a British Christian woman and an Egyptian Muslim man; an Irishman pretending to be an irrigation inspector to get a tasty meal and “borrow” ten francs from a priest; a French winemaker surprised that he would be imprisoned after he overestimated his foreign privilege by beating up an Egyptian tram conductor; And, eyewitness testimonies by Austrian barmaids pronouncing Islamic oaths. What Hanley’s book does is it upends what may have been thought to be established and predictable about nationality.

The label of nationality—the ever-recurring term that leads you through the book’s thematic kaleidoscope—creeps its way into the realm of individual identity, which was traditionally reserved for one’s name, occupation, place of origin, sect, and physical description. These attributes had to compete with “colonialism’s will to categorize populations and its pervasive expressions of power through small mechanisms and technologies and its modernity,” all of which were recognizable through nationality (though not the same as citizenship, which is a concept that would later become a key aim in decolonization movements).[10] This can be seen in Alexandria’s Maghribis up until the early 1880s, who were considered by local Egyptians as different, but not foreign. This invention of a nationality category, however, not only now made them foreign, but their status from a French colony also gave them further layers of protection (still short of the full legal protections that French nationals received) that unnerved locals, especially when nationality departed from the ordinary practice of the social into an exercise of its legality.

Identifying with Nationality is part of a trend that slowly crystallized in the mid-2000s and accelerated following the 2011 Egyptian revolution, which saw scholarship on Alexandria breaking the historical imperial-nationalist dichotomy that left little room for nuances. This shift took place amid a form of culture war between generations of Alexandrians, political positioning, and struggles to reconcile with the contradicting elements of the past. Perhaps beyond the book’s scope, it would have been worthwhile to give a brief analysis on modern Alexandria in the epilogue given the city was the ground zero and laboratory for the invented nationality category. Particularly because Hanley notes: “Alexandria was thus a bellwether for nationality changes that would spread worldwide in the twentieth century.” [11] As a resident of Alexandria myself, I wonder if modern Alexandria is a bellwether or troubling parable for the dysfunctions of nationality, as one sees the book’s longue durée projected into the present day as residents dwell on the debris left by nationality, nationalism, and an enduring colonial logic, which still scars Alexandria.

Hanley offers readers poignant lessons for our times, particularly given the triumph of nationality after World War I, which canonized smaller subsets of nationalities that we grapple with today, such as the “stateless, refugee, colonial subject, foreigner, and minority.”[12] Egypt’s Muslim-Christian relations, for example, were not without strain before the nationality category, but they were at least resolvable at the local level because differences were clearly known, understood, and mediated through a familiar pattern to the respective population center. Nationality, ironically, exacerbated religious tensions as it papered over differences and paved the way for state intrusion into local community matters. Even “Egyptian” did not hold much meaning for many Egyptians prior to the 1880s. The category only became important for bureaucratic reasons, not for membership of the watan (nation) or for paying homage to some pharaonic ancestry.[13] Rather, it was Egyptian elites who adopted the mantle of nationalism in order to wield “the resources of the state in their own interest” and saw to it that “nationalism expanded along the stolid avenue of self-interest.”[14] For the rest of the non-elite Egyptians, it would take decades to adopt the nationality label in any legal and nationalist sense. This reluctance can be explained, as Hanley puts it, because “the benefits of local status were often more obscure than its costs,” especially in terms of the burden of taxes and ruthless conscription, from which foreign nationals were free from.[15]

In traversing over four thousand cases, with over ten thousand individuals, and drawn from archives in five different languages from six different countries, Hanley delivers a superb piece of work in historical research, rethinking social history, and reevaluating national taxonomies, rather than assuming them. This book makes a significant and original contribution to the fields of transnationalism, citizenship, cosmopolitanism, comparative colonial studies, international law, Egyptian history, Alexandria’s urban history, and Mediterranean migration. It would appeal to both graduate students and scholars, but also to the informed public interested in these topics, as Identifying with Nationality, to its credit, does not intimidate the reader unfamiliar with legal jargon. The author has been merciful in making legal terms clearly legible, as well as subsuming them into captivating miniature narratives and vignettes that animate the sociolegal story of a bygone Alexandria. Therefore, it is not only a book that comprehensively adds to scholarship, but is ripe with countless gems to inspire future plays, poems, and stories.

NOTES

[1] Will Hanley, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 287.

[4] Ibid., 119.

[5] Ibid., 136.

[6] Ibid., 138.

[7] Ibid., 157.

[8] Ibid., 3.

[9] Ibid., 43.

[10] Ibid., 7.

[11] Ibid., 21.

[12] Ibid., 281.

[13] Ibid., 296.

[14] Ibid., 288.

[15] Ibid., 289.

Test

In the Eyes of the Beholder: The World, the Other and the Self from Arab and German Perspectives (Berlin)

The event on knowledge production took place at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities on 18 January 2020. I argued that if we do not address the scourge of passport restrictions and visa regimes, then the pace and orientation of holistic, transnational, and interdisciplinary knowledge production in the Arab world will continue to be skewed.

AGYA blurb: “With its contribution, AGYA invites the visitors to a critical examination of established concepts and patterns of perception of the world, the other and the self from German and Arab perspectives. AGYA is proud to present a program ranging from a panel discussion on ‘Scientific Worlds: Critical Reflections on Knowledge Production’, over a book launch of ‘Insatiable Appetite. Food as Cultural Signifier in the Middle East and Beyond’ edited by AGYA alumni and enriched by a tasting of different Hummus recipes, to a poetry slam and a photo exhibition on ‘Images of the Self and the Other in the Levant’”

Cosmopolitanism in Western and Islamic Thought

On 1-2 December 2019, the international AGYA workshop aims to explore the meaning of cosmopolitanism in Western and Islamic traditions and will provide a forum to investigate the mutual influences in the intellectual history of the concept in different cultural and intellectual traditions.

The concept of cosmopolitanism has always played an important role in philosophical and theological texts of various cultures, including Arab, European, Indian or Persian cultures. In its core, the concept of cosmopolitanism defines all human beings as world citizens— ‘kosmopolites’ in Greek—who thus are all part of a single universal community. The concept of ‘universality’ or cosmopolitanism also roots in Islamic theology and philosophy: in the history of Islamic thought, universalism is based on the concept of a shared humanity and equality. The unity of world citizens transcends all cultural differences or political borders, based mostly on a shared notion of morality.

In the eighteenth century, a cosmopolitan was a person that was open-minded, led a sophisticated life-style, and liked to travel. In current language, these are still some characteristics we are referring to today, when naming someone a cosmopolitan. Nowadays, cosmopolitanism is receiving more scholarly attention again: in the context of globalization, new (communication) technologies, and increasing digitization, there is a need to reflect in philosophical terms on the new prospects for the individual to interact and communicate with his or her fellow world citizens.

The AGYA conference focuses on intercultural exchange and its influence on the construction of moral and cultural paradigms. This is a rather new approach, considering the history of the concept of cosmopolitanism and the many contemporary moral, socio-political, and economic definitions existing in parallel today.

Bringing philosophy to the public: The Theatre of Thought Project in Egypt (lecture in Berlin)

I’ll be presenting a short talk on the Theatre of Thought project in Egypt and the ways in which philosophy can be brought to the public to address social problems.

The panel session starts at 3pm, 9 November 2019, at Freie Universität Berlin, Silberlaube Hörsaal 1a, as part of the AGYA conference that explores the place of humanities in Germany and the Arab world.

The coping mechanisms of society under authoritarian repression in the Middle East (lecture at the University of Amsterdam)

I will be giving a seminar “How society functions under authoritarian repression in the Middle East” at the Amsterdam Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Amsterdam on 7 November 2019, at 11am.