Published in Mada Masr, republished in openDemocracy, and Internazionale (Italian print edition)

“Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero,” Andrea cries in the 1938 play, Life of Galileo, by German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, to which Galileo responds: “No, unhappy is the land that needs a hero.”

Egypt can be that unhappy land, a land where farewell parties have outstripped homecoming parties. Where a young female doctor laments she wants to leave because “to give birth to a baby here feels morally wrong, it feels sort of illegal.” Where a juice seller sarcastically quips, “We no longer have time to think of anything else but survival, we don’t even have time to contemplate suicide.” When a country is mired in endless social and economic problems, and smothered in despair, the yearning grows for that batal (hero), that one human figure where all painful and complex abstracts will be realised within and resolved without.

Something happened in Egypt that short-circuited a sport that is often treated by governments of all persuasions as a distracting bread and circus for the masses. Something interrupted the despotic drive to stamp out the uniqueness from the flow of Egyptian life.

Enter Mohamed Salah armed with a moral code.

While Salah is seen to bring hope to many, he is an unsettling spectre that silently haunts the establishment, for he has options, international prestige and the perception of untouchability. He has grown to be more than a hero of football success. Salah is a different sort of hero, he is a hero of disruption, and a living paradox of a political voice without talking politics. Salah operates in a politics of juxtaposition in which his perceived immaculate persona is unconsciously contrasted with the familiar polluted forces of high politics.

While many of Egypt’s prominent and established figures seem to have an answer for everything, Salah shows up and we’re faced with difficult questions. Namely, why are we investing so much hope in one man? This is more than about the World Cup.

Salah is not a substitute for viable high politics. He is, after all, a football player, and a very good one at that, but his insertion into the volatile Egyptian climate sheds some light on what has gone wrong and why the current fervor around him can illuminate the question of Egyptian unhappiness.

Salah’s stance to steer away from politics, or from inadvertently disclosing his political leanings, has given him an amplified united base. Since the 2011 revolution, Egyptians have had to live with binaries: revolutionary versus counter-revolutionary, secular versus Islamist, civilian versus military, liberal versus hyper-nationalist, pro and anti-Brotherhood, among others. While many of these binaries have diminished under the shadow of the generals, the unity that has come in its place is a negative unity. It is almost always against something, such as terrorism, and when it stands for something, let’s say Egypt, it’s a nationalist straightjacket that is imposed, with no room for plurality of thought or voices.

Salah might just be the first figure in a while behind which pro- and anti-regime supporters can unite. In the words of an Egyptian doctoral candidate studying in California, “Salah is the reason I’m mending my relationship with Egypt.”

It has become commonplace to argue that unhappiness in Egypt is caused by high unemployment, poverty, dysfunctional education, censorship, a crackdown on independent voices, and overall human rights abuses. While there is no doubt these factors contribute to the misery of many Egyptians, there is something worse and pathological that lurks behind them all: The grim reality that new possibilities no longer emerge on the horizon. The dilution of hope that once offered the promise that unhappiness was a temporary moment, now feels for many like the ink of sadness has dried. Depression disarms you before repression even has time to put on its uniform.

For this reason, Salah is like a sudden assertion of human values within a dehumanising system. This did not arise when Salah helped defeat Congo, propelling Egypt into the World Cup last October. Astonishing football talent is not always enough to convert non-football watchers. Nor did his story of humble beginnings to stardom take hold in this moment. There was nothing original in any of these individual success stories. Perhaps because they remained just that: individual.

But then came the other, and equally decisive, side of Salah. Barely two weeks after this victory, and because of it, Salah was offered a luxury villa by entrepreneur Mamdouh Abbas. He politely declined the gift and suggested that a donation to his village Nagrig in Gharbia would make him happier. This move, along with many of his charitable acts, for non-football fans, including myself, was thunderous to say the least, and swayed us to his camp.

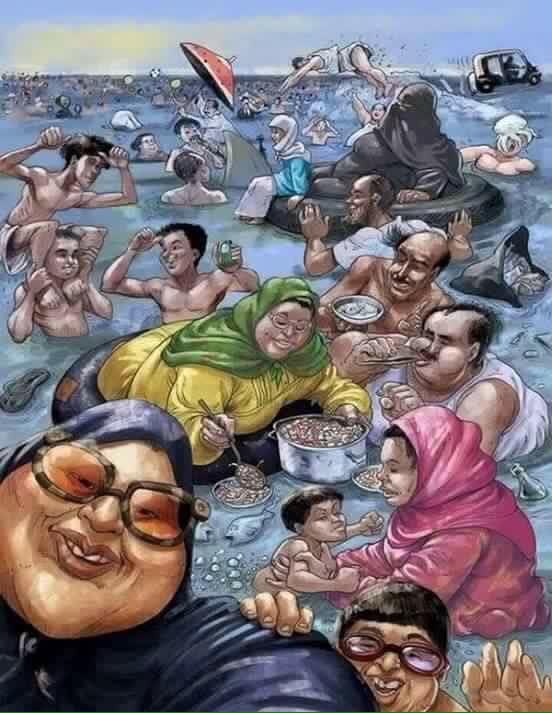

To put the implications of this act in a wider context: Cairo’s highways are nauseatingly choked with billboards flaunting the latest exuberant luxury real estate and gated compounds. It is an assault on the senses of millions of Egyptians who are puzzled as to how such developments take place in an era of painful austerity measures, in which they are being asked to continually sacrifice. The billboards, almost always in English and at times with white, blue-eyed European faces, loudly proclaim, “It’s time to think about you,” and, “This time it’s personal.” It is not enough that Egypt’s capitalism on crack and real estate speculation is skewing the economy, but it also ramps up hyper-individualism, greed, and various strands of self-hatred.

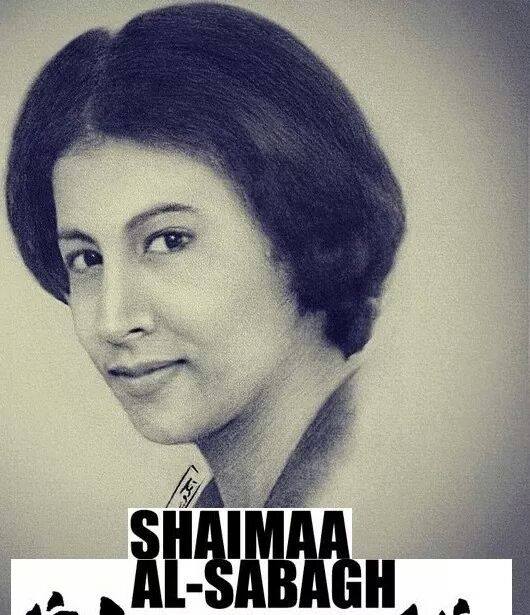

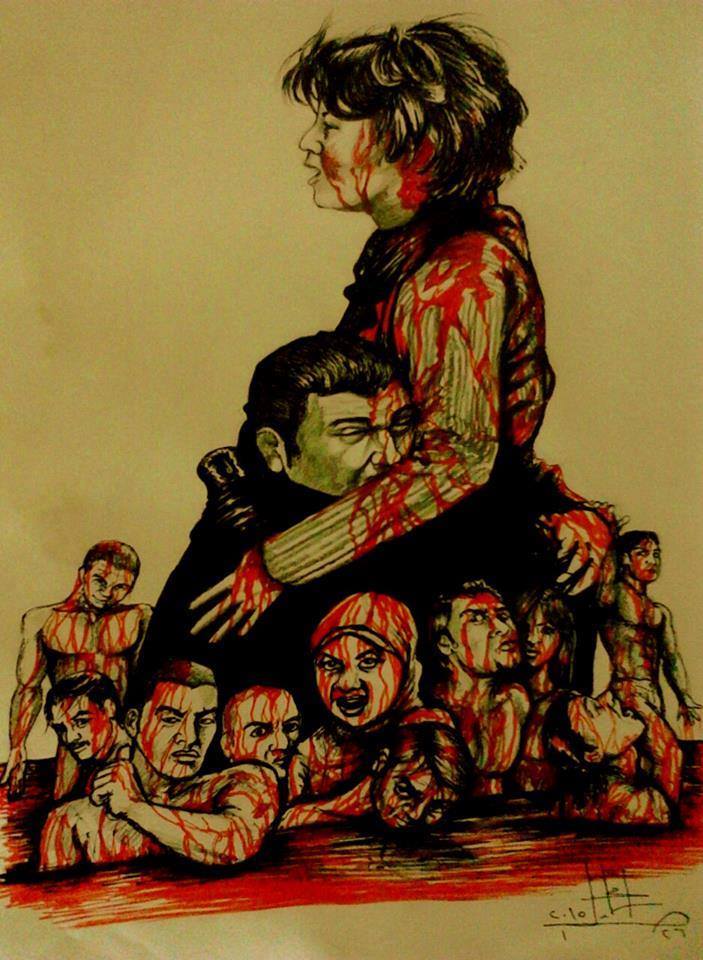

Salah’s rejection of the villa was a violent piercing into a culture of the grotesque and excessive, and signified his upholding of the values born, or crystallized, during the 2011 revolution that put the common good above all. His refusal was a significant breach in the business-as-usual patronage and wheeling and dealing circles. If Salah was loved for his victory over Congo, he was now respected more for this move and the many charitable stories that emerged, making it obvious that this has been his character for a long time, and that he didn’t reinvent himself for PR purposes. Love and respect are two different beasts. Egyptians have long missed looking up to someone who commands respect, at least someone who is not in exile, in prison, or long dead.

In recent years, Egyptians have had to live with the exhausting spectacle of doublespeak in which official interpretations are often in conflict with lived realities and common sense. The train heading to Alexandria is declared to be on its way to Aswan, as veteran journalist Yosri Fouda once put it. This war of attrition on rationality has plunged Egyptians deep into a spiral of conformity, scepticism and indifference toward each other. The idea of the higher good receded as officialdom continued, in Czech philosopher Václav Havel’s words, “not to excite people with the truth, but to reassure them with lies.” The intervention of Salah did not necessarily change all that, nor did it reverse the Orwellian trend, but he did help restore meaning to terms that had become scrambled: dignity became dignity again, principles became principles, kindness became kindness, and happiness became happiness.

Salah touched on another existential question within Egyptian state and society: the strong desire for international recognition. This phenomenon weaves its way through Egypt’s modern history. There have been concerted efforts to export Sisi’s branded Egypt, for example, with the new Suez Canal project billboards dotting New York’s Times Square with the slogan “Egypt’s gift to the world.” Salah, instead, lived up to fulfilling that slogan in a much more dramatic and compelling way. In fact, Salah has arguably had more impact on the world’s positive views of Egypt than all the recent years of tourist campaigns, international conferences and mega projects combined. In light of this, mentioning Salah in conversation can give many Egyptians a feeling of breathlessness, tingling hands and a sensation of weightlessness.

This in part has to do with the function of happiness and meaning. If the regime is not suffering from cherophobia (fear of happiness), it believes it can commodify happiness by stating it intends to make “Egyptians among the world’s happiest,” or through the recent discussions with the UAE’s Ministry of Happiness to “export” some of their cool psychedelic juice to Egypt.

Happiness is a question that spans a history of philosophical musings, from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, to Al-Ghazali’s Alchemy of Happiness, to Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols and the Antichrist. All of them would shun the Anglo-inspired utilitarianism of John Stuart Mills that speaks of happiness as the ultimate net objective and has been largely repackaged for neoliberal modernity, rather than a meaningful higher life that produces happiness as a by-product. In other words, you cannot separate the attainment of happiness from respect for justice, dignity, honour, etc. It doesn’t seem to phase the authorities that happiness is meaningless without rescuing vibrant citizenship, opening public spaces, providing fair trials, encouraging pluralism, and preventing overall existential meaning from being fragmented.

Salah offers glimpses into the voids spawned by the above fractures as he communicates not only on the instrumental level of football success, but with meaningful and empathic qualities that come with an honourable character. It is no wonder that Salah was able to inspire calls to a drug user helpline to shoot up by 400 percent.

Salah’s fame, coupled with his stance on religion, comes interestingly at a time when many Egyptians are renegotiating their faith, identity markers and boundaries. The norms of what once constituted a religious person are breaking down under the weight of the country’s endless contradictions. All this takes place beneath the purview of a state that uses religion to arbitrarily police the public space, and preachers who continue to push a baroque Islam at the expense of the religion’s humble essence.

The rise of a widespread spiritual passivity contrasts with Salah’s faith, which has come to animate his public life. He saw no need to dismiss or distil his Muslim identity, even after he achieved a turbo-charged social mobility and stardom. This is not lost on many. The sight of Salah’s veiled wife, Maggie, by his side on a green oval in a European city before the eyes of millions, is a hypnotic sight to Egyptians (and the rest of the world) precisely because it is unusual, particularly at a time of heightened anxieties toward Muslims in the West. “I respect him as he is not embarrassed nor does he try to hide his veiled wife after all that success,” an Alexandrian barber says.

It is for the same reasons that Salah can sprout pan-Arab and pan-Islamic wings across the Arab and Muslim world. He has made it into Lebanon’s graffiti scene and protest ballots in the Lebanese elections (just like Egypt) to a bizarre planned peaceful protest outside the Spanish embassy in Jakarta after the injurious tackle by Sergio Ramos. The Arab world’s traditional idea of a leading, strong, vibrant, noble and outward-looking Egypt – one that spearheads the arts, preserves the seat of intellectual Sunnism, champions pan-Arabism, and stands up for the Palestinian cause – is projected onto Salah with deafening force. Between prostrating on the grass and raising his index fingers to the heavens, hundreds of millions of Muslims are drawn to this well-understood language of piety.

But this attraction transcends culture and religion. As the western world is bogged down in neoliberal sterility, rampant consumerism, loneliness, high-level scandals, populism, xenophobia against refugees and immigrants, anti-Muslim bigotry, anti-Semitism and fake news, the multi-layered Salah – the intimately relatable footballer and loving father who kicks a ball with his daughter Makka – stands out like a moment of truth and living universality, with a mammoth mural recently going up in Times Square reflecting his larger than life image.

Albert Camus wrote to an estranged German friend in 1943: “I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice. I don’t want any greatness for it, particularly a greatness born of blood and falsehood. I want to keep it alive by keeping justice alive.”

Salah perhaps embodies this ideal. That love of country does not require drums and chest-beating, but grace, sincerity, modesty and charity. He is a reminder to Egyptians that there exists a better human nature in a landscape barren of prominent reverential role-models. To Egypt and even the rest of the world, Salah is the outlier that proclaims the alternative to nationalism is not treachery but civic responsibility, the alternative to stifling religious conservatism does not always have to be apathy or mockery of the sacred, but breathing faith into a sound value system, and the alternative to injustice can be forgiveness. Ultimately, people had almost forgotten what humility among those with renown looks like. Particularly, a humility that is relentless and consistent, despite being trialled under the stadium floodlights and the stars sprinkled across the Liverpool night sky.

Salah is the rare homecoming party Egyptians have long awaited. His face on dangling lanterns lights up dark alleyways, and his colourful posters germinate over the debris of fading election posters in a country that sees official and media-manufactured heroes reckon with publicly-anointed heroes.

While it cannot be implied nor expected that Salah could impact the political situation in Egypt, his animated existence spotlights entry points back into the realm of authenticity. He widens the moral imagination of an attentive public and parades the possibilities that infer that the rhythm of life involves more than birth, marriage, death and even sports. He also raises questions that many power-holders will have to grapple with eventually, someday: That, above all, there are reasons why people ache for heroes in the first place. — What have you done to make them this unhappy?