Published in Mada Masr. (Click here for the Arabic translation). Republished in the Asia Times.

Published in Mada Masr. (Click here for the Arabic translation). Republished in the Asia Times.

I have grown accustomed to gradually seeing religious festivities being disemboweled of their meaning, whether it’s the entertainment-saturated Ramadan, or the hyper-commercialized Christmas. But the Islamic Eid al-Adha (Feast of the Sacrifice) stands out starkly, as it has been built on an all-encompassing annual spectacle, with the blood of sheep and cattle running through the veins of Egyptian cities. To live in a part of Alexandria surrounded by butchers, as I do, is to be unfortunately placed at one of the city’s aorta.

Eid al-Adha, which celebrates the Prophet Abraham’s sacrifice, is rich in meaning and symbolism, from the perseverance of the human condition to the traditional binding of families and community, as well as allowing, at the very least, a metaphorical reaching out to Jews and Christians who can relate to the tribulations of Abraham. More so, given that many poor Egyptians are “vegetarian” by default, as they can rarely afford meat, Eid is an opportunity to put meat on their tables. This is not to mention the money and other charitable gifts that are given out generously on this festive occasion.

When it comes to charity, Eid Al-Adha is an exemplar. When it comes to the actual sacrifice, it has become frighteningly lacking.

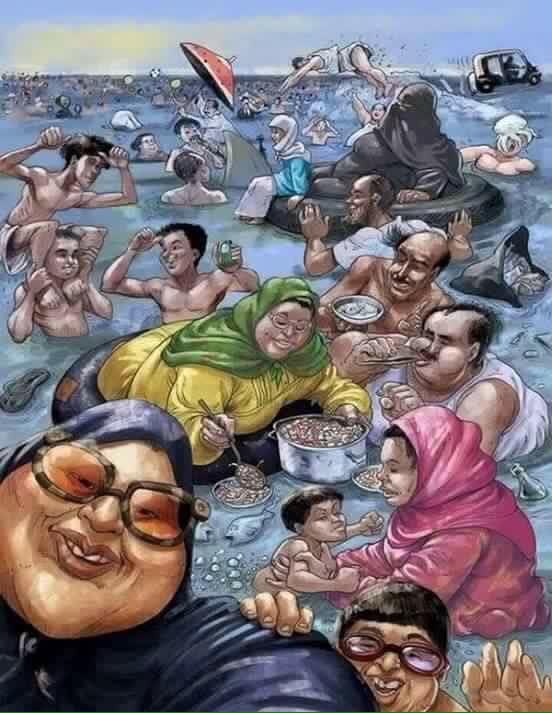

Egyptian society over the years has developed an unhealthy obsession with ostentatious displays of piety. Eid al-Adha has regressed to the point where public piety meets peak voyeurism, leading to the collapse of any semblance of a public sphere. The origins of this problem came with urbanization that saw the ritual move from farms and slaughterhouses to the streets. And for a long time, the practice was undertaken in the building’s manwar (interior) by a few families. Now, driven by the flaunting of wealth, it has reached an industrial scale, with minimal supervision, regulation or consensus. The authorities, despite being against it and issuing fines here and there, would rather react swiftly to one innocent protester holding a sign than the instigators of thousands of liters of blood clogging the fragile drainage system, overwhelming the minimal sanitation standards and releasing the smell of dead animals into the air.

The withering of Islamic ethics regarding the practice of slaughter is obvious when basic questions are not even asked as to why animals are kept in dire conditions in the lead-up to their fate, why they are forced to witness others being slaughtered and why are children watching this bloodbath. What is halal anymore?

Moreover, the implication is that the animal is the centerpiece of the festivity, obscuring the underlying message and normalizing our problematic addiction to meat.

Meat consumption was extremely limited in the early days of Islam. The Prophet and his companions were semi-vegetarians. One, in fact, was an outright vegetarian. The sources consistently showed the Prophet’s favorite foods to be dates, barley, figs, grapes, honey and milk, among other non-meat foods. The Prophet never ate beef, going as far as saying, “The meat of a cow produces sickness, but its milk is a cure.” The Caliph Omar warned to, “Beware of meat, because it is addictive like wine.” Historically, it was only rich Muslims who could afford meat, and it would only be eaten on Fridays, while the poor had to wait for Eid to eat meat.

These historical factors ought to be considered in light of the need to reframe Eid Al-Adha away from the morass it has been dragged into. Perhaps meat can be treated as that rare luxury that is eaten infrequently across the social strata. I’m no vegetarian, but the excessive quantity of meat produced and consumed, the social signifiers that accompany it, the deep inequalities that it sharpens and the troubling medical problems that it exacerbates, not to mention the additional pressure meat production places on the planet, means that there is an urgent need to diversify cuisines and elevate non-meat options.

Whatever is happening, it is no longer about the story of Abraham, it is something that you just do because you did it last year and you will do it next year as well.

More and more, each year, we experience a nihilist Eid on the streets. The butchers don’t know why they are slaughtering, the donors don’t know why they are paying for it, the public doesn’t know why they are witnessing it, and the sermons have hit a tone-deaf level. The only ones who seem to have some awareness that something is not quite right are the sheep, goats and cattle.