Click here for the Facebook event page

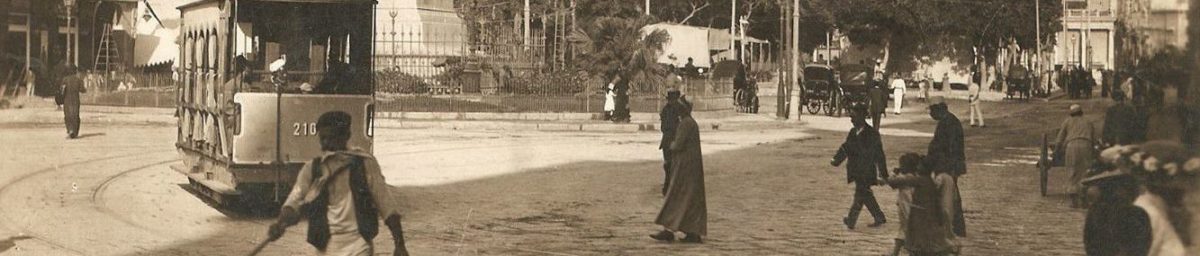

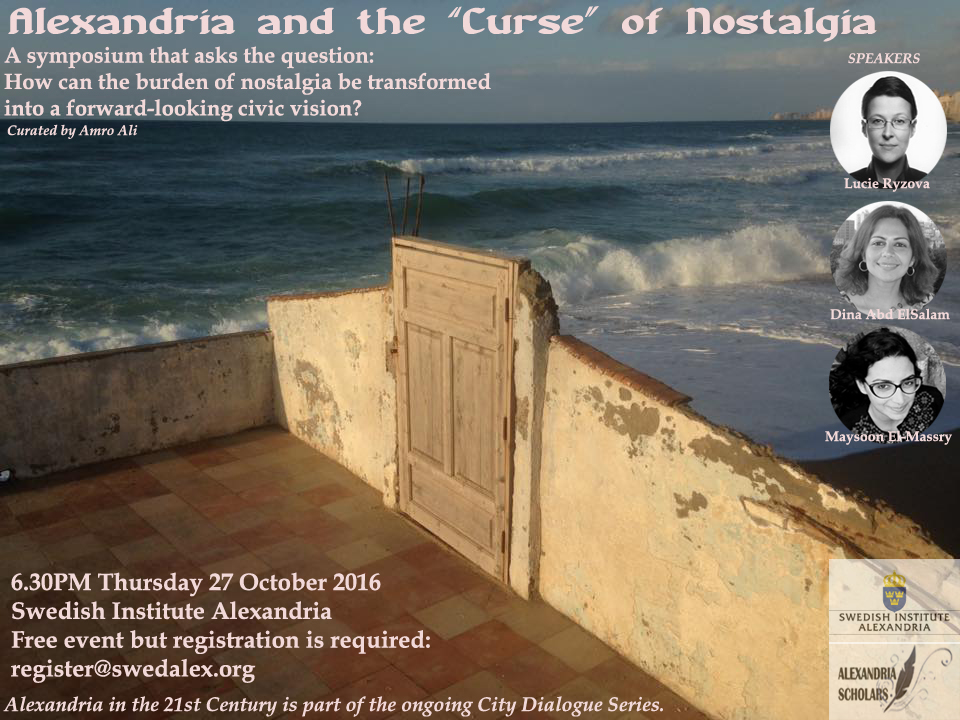

Alexandria and the “Curse” of Nostalgia (Second symposium of the City Dialogue Series)

Click here for the Facebook event page

Alexandria and the Search for Meaning (The City Dialogue Series)

(Click here for flyer link)

The Swedish Institute Alexandria partners with Alexandria Scholars in facilitating an intellectual project that brings together international and national figures to converse with local Alexandrian actors from academia and civil society.

The aim is to discuss and explore prospective solutions to Alexandria’s challenges through the terrain of historical, urban, and philosophical analysis – derived from Alexandria`s pluralist origins. The question we raise is how can the city better understand itself and its positioning in Egypt, Mediterranean basin, and the world given what it used to be as well as its current potential?

The monthly sessions are driven by the view that the public should be recognized, and elevated, as the primary ideal, and Alexandria’s present difficulties in attaining pluralism and civic responsibility is partially tied to the city’s loss of civic meaning and identity as a pivotal and dynamic metropolis on the southern Mediterranean coast.

The first of these monthly sessions will be held at SwedAlex premises on Monday 10h of October at 6:30 pm. It will raise a key question attributed to Alexandria`s contemporary challenges: How can Alexandria reposition itself in the modern world and what are currently the city’s strengths, limitations, and sense of identity?

The four monthly sessions will each, respectively, raise a key question attributed to Alexandria’s contemporary challenges: (a) How can Alexandria reposition itself in the modern world and what are currently the city’s strengths, limitations, and sense of identity? (b) Can the specter of nostalgia that haunts Alexandria be refashioned into a forward-looking civic vision? (c) What ideas and methods can be undertaken to plug the gaps in the dysfunctional education system, and ensure students acquire conceptual thinking and critical skills? (d) What approaches can be implemented in order to endow, or sharpen, Alexandria with a clearer identity and coherent narrative? The sessions will be in English with Arabic translation provided.

Speakers:

Speakers:

Yahia Shawkat – Co-founder & Research Coordinator of 10Tooba).

Reem Eltaib – Manager at Radio Tram and former assistant to governor of Alexandria, Hany el Messiry.

Karim-Yassin Goessinger – Founder and program director of the Cairo Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Curated by Amro Ali (lecturer in sociology at the American University in Cairo, and founder of Alexandria Scholars).

Please register your attendance by sending an email to register@swedalex.org

* This lecture is in English language.

* Limited seats available. Priority for early registration.

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/955615517882221/

Next Events:

Session two: Alexandria and the “Curse” of Nostalgia (13 October 2016).

Session three: Alexandria and Miseducation System (10 November 2016).

Session four: Alexandria and the Reconstruction of a Civic Ethos (8 December 2016).

Burkinis are accepted, if on a poor woman scrubbing France’s floors

Republished in OpenDemocracy

The legendary African-American novelist James Baldwin once noted on his trip to France, in 1949, the extent of violence “Paris policemen could do to Arab peanut vendors.” The crime of an Arab, it seems, was to be visible, and therefore it was safer for Arabs to be invisible, with the help of the French authorities – be it through the prison cell or the ironing out of their cultural distinctions in the public sphere.

Yet I have always found it quite peculiar this French manner of discriminating against the visible in order to make them invisible – often the people France needs the most.

My encounter with French racism and hypocrisy came about when I stayed in northern Paris in the autumn of 2009, at a bed and breakfast place. I was hosted by an upper-middle class mother who, during a chilly October morning over breakfast, told me about her work in art/decor and went on to disclose her politics as “left and progressive.”

Yet soon enough she mouthed off racist statements against Arabs (apparently I was the “civilised” Arab that would be sympathetic to her rants). Then she moved onto, specifically, abusing Algerians, then onto Muslim women who wore the veil. The only “concession” she could make was that French colonialism brought its “subjects” back in the form that France has to do deal with today. Before I could reply, she had to “urgently” leave for work. Exhausted from her conversation, I sat back at the breakfast table, in a beautiful 1850s apartment from the Baron Haussmann era, trying to wrap my head around all that she had said (I usually hear bigots out to the end, and try to deconstruct their line of thinking).

At that point, I heard the echoes of Arabic singing reverberating through the courtyard of the building’s interior. I peered out the window to see a group of Algerians/Moroccans fixing the broken pipes. I gazed down with despondence and voiced to myself: “How utterly sad France is, many of you are the backbone of this country. The French need you but don’t want to see you.”

This set off a series of questions that I would ask Arab residents of the city and make careful observations of race relations.

There was something haunting and disturbing about the necessity and invisibility of these workers. This shed some light on French hypocrisy and their craven need for cheap labour that often comes out of France’s thriving shadow economy, that mutually complements the official economy, which is populated with immigrants, their descendants, and refugees.

The French need Arabs for service and maintenance, but only when such Arabs are doing so out of sight.

The French need black Africans in restaurants, but as long as they are in the kitchen and not the ones serving the customer (more than enough East Europeans to do that).

The French don’t mind the poor Muslim woman who is veiled as long as she is scrubbing their apartment and office floors on her knees but God forbid if her kind invades French recreational spaces and attempts to be equal on her terms.

The Burkini was a non-issue elevated to a political and identity war. It took a non-issue to expose, again, the hypocrisy of France’s ideals and understanding of liberalism and feminism.

The poisonous sting of hypocrisy will not only consume the intended target – Arabs and Muslims. But it sets irreversible precedents and opens up pores in the nation’s body politic to illiberal infection from all directions. The rise of the far right is one obvious example, but they are just one manifestation of a larger ominous current that is yet to come. One should never think the xenophobic tide will stop at Arabs and Muslims. Hatred never runs on rational thought, it is irrational and all-pervasive, and will seek new targets once it exhausts its initial victims. Supposed liberals and feminists are not only aiding and abetting in this assault, but are conducting a grievous self-harm that will see their legitimacy undermined, value system compromised, and ethical standards dismantled. The consequence is that it will leave them vulnerable, in a worst-case scenario, to French anti-democratic political forces that will seek their destruction or cooptation. French history is testament to such undesirable possibilities.

When Baldwin was imprisoned in Paris for an unintentional petty crime (he used bedsheets that his acquaintance had stolen from another hotel!), he observed that, unlike the other lifeless clay-like prisoners in his cell, the “North Africans, old and young, who seemed the only living people in this place because they yet retained the grace to be bewildered.”

The woman on the beach in her human quest to be visible, had the grace, understandably, to be bewildered. A large swathe of your citizens are bewildered, France. The world is bewildered, France.

References

James Baldwin, “Equal in Paris” in James Baldwin, Collected Essays (New York: Library of America, 1998) pp. 101-116.

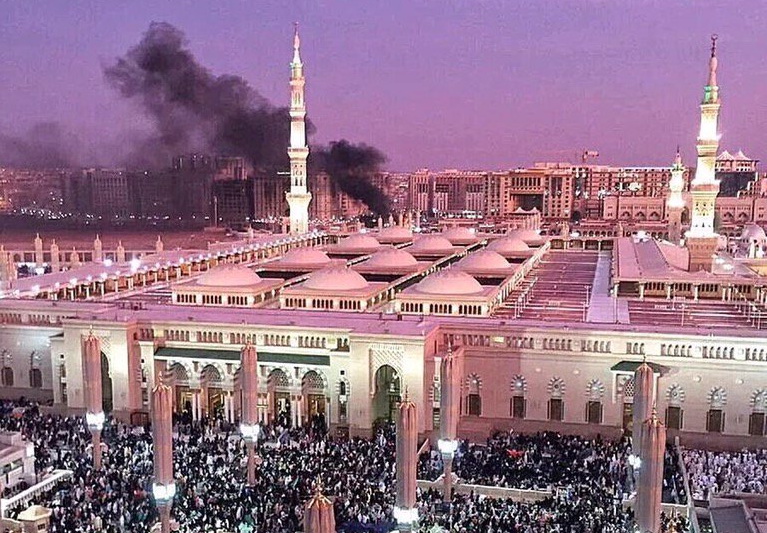

As Medina reveals: ISIS is not hijacking Islam, it is actively at war with Islam

If a self-proclaimed Catholic group bombed the Vatican’s St. Peter’s Basilica and constantly killed scores of innocent Catholics, then we would deem such an entity, in various degrees, as an anti-Catholic terrorist group.

Likewise, ISIS is not a radical Islamist movement as much as it is an active anti-Muslim, terror movement.

ISIS kills more Muslims than any other religious followers, bombs Muslim-majority cities, fights against every known Islamic principle, destroys the heritage of centuries that was not harmed by earlier Muslims, and they actively pervert the peaceful month of Ramadan.

ISIS is not misinterpreting Islamic texts, it is burning Islamic texts.

ISIS is not seeking Muslim hearts, it is ripping out Muslim hearts.

ISIS is not hijacking Islam, it is actively at war with Islam.

ISIS is anti-Quran, anti-Islamic tradition, anti-Islamic history, and anti-Prophet.

ISIS sees nothing sacred, neither time, space or place.

This is the same ISIS that hates Muslims but loves the European far-right and Trump. For who else will indirectly help ISIS thrive?

Now they bomb, among other cities, the holy city of Medina where Islam’s Prophet rests.

How many more sickening anti-Muslim, if not anti-human, acts does it take for a diabolical group to be dissociated from a religious body in the eyes of the world?

The Middle East: World Crisis? A Conference

I will be giving a talk on 4 June in Berlin regarding Egypt’s role in the region vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia and Turkey, with a focus on how the 2011

revolution impacts the legitimacy and narrative surrounding Egypt’s foreign policy decisions.

“The Middle East is now subject to a conjoncture of political instability, economic dysfunction, growing religious extremism and seemingly endless war which is bringing misery and hardship to tens of millions of its citizens, and with a capacity to increase already shocking levels of violence in a zone stretching from the Afghan-Pakistan border to the southern shores of the Mediterranean.

In the late summer of 2015 the crisis took on a new and frightening dimension. A year of escalating violence in Syria and Iraq, driven by the Islamic fanaticism of ISIS, has unleashed a huge wave of refugees fleeing for their lives and seeking sanctuary mostly in the member states of the European Union.

With the added violence of the terrorist attacks in Paris and now Brussels, this has become for Europe perhaps the gravest crisis of its kind since the Second World War and engages the continent in the day to day affairs of the Middle East in ways that are unprecedented. Our conference, taking place at the heart of the EU in Berlin, will we hope contribute towards an understanding of the region’s multiple crises, and explore paths to their solution.”

Organised by the New York Review of Books Foundation and the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP.

Panel III: Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia: Regional Powers Manque?

Time: 2:30 PM 3 June 2016

Chair: Sarah Hartmann, DGAP

Amro Ali, University of Sydney

Professor Bülent Aras, Sabancı University, Istanbul

Professor Madawi Al-Rasheed, The London School of Economics

Venue: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik

Rauchstraße 17,

Berlin, Germany

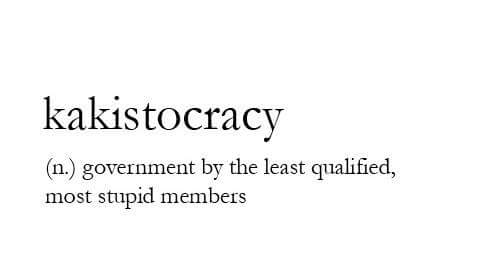

Kakistocracy: A word we need to revive

“Stupidity does not consist in being without ideas. Such stupidity would be the sweet, blissful stupidity of animals, molluscs and the gods. Human Stupidity consists in having lots of ideas, but stupid ones. Stupid ideas, with banners, hymns, loudspeakers and even tanks and flame-throwers as their instruments of persuasion, constitute the refined and the only really terrifying form of Stupidity.” – Henry de Montherlant, Notebooks, 1930-44

How and why did a word so relevant for our times be pushed almost to oblivion? In a world where stupidity penetrates multiple levels of government, policies and personalities; it is strange that the term coined to best describe it has actually ended up in the endangered and forgotten words books. Stupidity in governance needs to be treated as a political problem, and kakistocracy can best capture this problem.

Kakistocracy is the government of a state by its most stupid, ignorant, least qualified and unprincipled citizens in power. Kakistos means “worst” which is superlative of kakos “bad” (perhaps also related to “defecate”). Along with kratos (see -cracy) meaning “power, rule.”

The first documented example appeared in 1829 in a book called The Misfortunes of Elphin, written by the English novelist and poet Thomas Love Peacock.

They were utterly destitute of the blessings of those “schools for all,” the house of correction, and the treadmill, wherein the autochthonal justice of our agrestic kakistocracy now castigates the heinous sins which were then committed with impunity, of treading on old foot-paths, picking up dead wood, and moving on the face of the earth within sound of the whirr of a partridge.

By 1876, the American poet James Russell Lowell was clear regarding its political implications when he wrote in a letter:

What fills me with doubt and dismay is the degradation of the moral tone. Is it or is it not a result of democracy? Is ours a “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” or a Kakistocracy, rather for the benefit of knaves at the cost of fools?

Yet given the prevalence of the problem it describes, the word is strangely not appreciated and underused in the twentieth and twenty-first century. The University of Sydney library search shows, since 1917, a modest use of the term only to suddenly peak after 1981. Perhaps because it corellated with the rise of neoliberalism which has an intimate relationship with stupidity, or to put it more harshly in the words of Mexico’s Subcomandante Marcos: “Neoliberalism is the chaotic theory of economic chaos, the stupid exultation of social stupidity, and the catastrophic political management of catastrophe.” Kakistocracy as a term then tapers off only to make a modest rise around 2008, when eight years of Bush hinted the word might be of some significance. Yet by rise, I am speaking of less than a dozen texts. Overall, Google Scholar sees the word employed merely 204 times in the scholarly literature. A few reasons can explain this neglect.

First, the heavyweight dictionaries have not come to a consensus on the term – Merriam-Webster and Collins list kakistocracy, but Oxford and Cambridge do not. Also there is little sign the term has spread from the English language (apart from its Greek roots) and made inroads into other languages – This could have ensured its widespread use.

Second, according to Phrontistery, there is a staggering 169 forms of governments, including bizarelly enough, diabolocracy (government by the devil) and pornocracy (government by harlots). I guess it must have been an issue at some point in time for someone to invent such terms. But it means kakistocracy is in competition with other robust and not so robust terms – creating an etymological dystopia.

Third, kakistocracy can be abused. It is not difficult to fathom from historical texts that every generation seems to consider their government as being the worst ever kakistocracy. The term is invoked to tarnish any government one does not agree with – acting as nothing more than a sophisticated guise for unwarranted attacks. There is even a risk the term could become too “mainstream,” losing its meaning and impact similar to the fate of, for example, soft power.

Finally, it is my suspicion that analysts have preferred to use kleptocracy (rule by thieves) instead. But kleptocracy is not the same as kakistocracy: They do both capture the element of least qualified or the worst, but with different meanings. Taking a reductionist stance for the sake of making the point, Putin’s regime is more of a kleptocracy, a regime ruled by thieves and thugs but that does not mean Putin is politically incompetent or stupid. Sisi’s Egypt shows elements of kakistocracy where stupidity is clearly characteristic of the personalities and decision-making process. This I have examined in detail in last year’s piece Egypt’s long walk to despotism that attempts to make sense of the relationship between Egypt’s political order and the stream of abusurdies we have witnessed over the past few years. Yet both Egypt and Russia share elements of kakistocracy and kleptocracy. There is no mutual exclusivness and clear demarcation lines in this debate.

Yet the flipside of not enganging with kakistocracy has left the word to the mindless circulation of memes and right wing shrills like Glenn Beck who sporadically employ it (and mispronounce it) to attack the Obama administration. Love him or hate him, Obama and his administration is far from anything resembling a kakistocracy. Bad decisions are not always a sign of kakistocracy.

Some might argue kakistocracy is a form of tautology, that stupidity can be rife through established democracies and dictatorships without needing to resort to a special word, or that behaviour is not enough to explain governance. I would argue otherwise: words matter, as a more sophisticated approach in the use of kakistrocracy, even if endowed with new meanings, can bring in a sharper conceptual understanding of incompetence, help provoke thought and new approaches to the relations of power.

Therefore, kakistocracy will not only capture rule by the “stupid” and the “worst,” but how they push human relationships, that form the controlling governmental machinery, into a degenerative state. The term will be more receptive to seeing a movement of ideas from psychology and sociology into the political science and international relations field. It will provide an organising concept to converse with its established kinfolk in the form of anti-intellectualism, mediocracy and nepotism.

To my knowledge, we are not even at the stage of seeing conferences on the dynamics of political stupidity, nor understanding the accumulative processes over the years that have brought about a large number of kakistocracies and stupidity as the standard bearer across much of the world.

Either kakistocracy gets used and thoroughly examined or a Trump presidency will force us to do so.

Update: Two worthwhile comments regarding this post come from Marco Lauri (Facebook). The first better explains the term pornocracy and the other proposes one way of sharpening kakistocracy.

“‘Pornocracy’ is a term with a long and very respectable history – used, I think, first in the Renaissance to describe the role of concubines in the running of the affairs of the Papacy during the tenth century – of course it was derogatory and never actually intended to describe a form of government as such.”

“I think that “kakistocracy” should be reserved for systems that positively select for stupid people to be put in charge. This is historically irrespective of the actual form of government (the idiots may be either appointed by an idiot despot, or elected by a dumbed electorate, or forced through the ranks by a purposeful mob, etc.). However, I support the notion because there are arguably common factors worth studying that enable the selection of stupid people. Sycophants are probably the easiest element to see and explain, but not the only one. There must be a whole ecology of systemic political stupidity awaiting analysis.”

Giulio Regeni e gli italiani in Egitto che denunciano il regime (Italian translation)

Published in Italy’s Internazionale magazine. Originally published in Mada Masr (in English).

Tra il deserto immobile che “incessantemente si consuma” e il mare perpetuo che “manifesta furiosamente il rinnovamento” si è formata la “mia prima visione della realtà”.

Sono le parole di Giuseppe Ungaretti, poeta italiano nato ad Alessandria. Le scrisse nell’Egitto degli anni trenta. Oggi nel paese è presente una comunità transnazionale sempre più numerosa, emersa all’ombra delle rivolte arabe, soprattutto dopo la rivoluzione egiziana. Questa comunità si colloca tra un’Europa vuota di ideologie e in preda all’austerità e un Medio Oriente politicamente spietato e radicale. Ma chi sono, e qual è la loro “visione della realtà”?

Gli italiani transitati in Egitto negli ultimi anni illustrano bene le caratteristiche di questa comunità che con le sue idee supera le nazionalità e i rapporti geopolitici.

L’orribile morte di Giulio Regeni, il dottorando italiano torturato e assassinato mentre si trovava in Egitto per fare ricerca sul sindacato, ci impone di osservare più da vicino i saperi prodotti da queste persone sullo sfondo di rapporti storici, politici e sociali spesso tesi da un capo all’altro del Mediterraneo.

“La ribellione era necessaria nell’Europa delle politiche di austerità, e l’atto di ribellione stava accadendo in Egitto. L’Egitto ci stava ispirando a sfidare la nostra realtà”, mi ha detto Lucia Sorbera, una storica e femminista italiana di Pisa che per molti anni ha fatto ricerca in Egitto.

Prima delle rivolte arabe nel 2011, l’interesse degli attivisti italiani in Medio Oriente si è concentrato soprattutto sulla lotta palestinese. Dopo le rivolte però, dopo che piazza Tahrir ha esportato una forma di protesta spettacolare, tanti intellettuali italiani hanno cominciato a preoccuparsi dei paesi a sud del Mediterraneo, soprattutto l’Egitto. Nel giro di poco tempo i nomi di rivoluzionari egiziani come Alaa Abd El Fattah e Mina Daniel hanno cominciato a circolare nelle università italiane e tra le comunità di attivisti.

Giulio and the Italians of Egypt

Published in Mada Masr

Italian translation in Internazionale

Between the static desert that “ceaselessly wears away” and the

perpetual sea that “furiously manifests renewal” is constituted

“my first vision of reality.”

These are the words of Alexandrian-born Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti. He wrote them in the Egypt of the 1930s. Today, a growing transnational community of thinkers has emerged in the shadow of the Arab uprisings, particularly the Egyptian revolution. This community exists between an ideologically devoid and austere Europe, and a politically merciless and radical Middle East. But who are they, and what is their “vision of reality”?

The Italians who traversed Egypt in recent years stand out, and are illustrative of this transnational community that exists today and whose ideas trump nationality and geopolitical relations.

The horrific death of Giulio Regeni, the Italian PhD student who was tortured and murdered while in Egypt doing academic research on trade unions, has perhaps mandated us to take a closer look at this intellectual community that produces knowledge against the backdrop of often tense historical, political and social relations across the Mediterranean.

“Rebellion was much needed in the Europe of austerity policies, and it [the act of rebellion] was happening in Egypt. Egypt was inspiring us to challenge [our reality],” Lucia Sorbera, an Italian feminist historian from Pisa who has researched Egypt for many years, told me.

Prior to the Arab uprisings in 2011, Italian activists’ interest in the Middle East was primarily focused on the Palestinian struggle. But after the uprisings, after Tahrir Square exported an invigorating theatrical protest that made many on the Italian peninsula turn their faces to the south, many Italian intellectuals became preoccupied with south Mediterranean countries, especially Egypt. Soon enough, the names of Egyptian revolutionaries, such as Alaa Abd El Fattah and Mina Daniel, were becoming known throughout Italian university campuses and activist communities.

This was quite a change from a year earlier. In 2010, the Egyptian state made a strange appearance in Italian affairs after former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi secured the release of his underage Moroccan mistress, “Ruby the Heart-stealer” (Karima al-Mahroug), by telling police she was then-President Hosni Mubarak’s niece.

After Regeni disappeared for seven days, only to be found tortured to death, the pro-state media struggled to justify the murder. There were half-hearted accusations of espionage, but they did not sell well — relatively harsher statements only came in response to the European Parliament resolutioncondemning Egypt. This might have been due to the fact that Regeni was Italian, and there was no handy history of interventionism that the state and its cronies could bank on to promote an espionage charge or propagandize their usual conspiracy theories. It is safe to say if Regeni were American or British, it would have been far easier to dig up that country’s history of interventionism in Egypt as implicit justification for his death. But for Italy, there was no strong case in this regard.

In terms of public perceptions, Italy does not invoke any immediate threat in the public imaginary. Pro-Italian sentiments are not uncommon — from elite writers who praise historic relations with Rome that date back to classic antiquity, to the street vendor who tries to sell you a dubious “da Itali!” (It’s Italian!) leather belt, to my plumber who markets me a clearly marked “Made in China” water pump as being originally from Italy. Italy is more often than not perceived as a trademark of class, elegance and relatable credibility. To many Egyptians, for one reason or another, Italians are familiar Europeans.

Italians fit well into Egypt’s current crippling nostalgia of our bygone neighbors — a cosmopolitan narrative of a “once-had-and-lost-modernity,” as social historian of modern Egypt Lucie Ryzova puts it. It is a narrative that the current pro-government elites use when they say that the president “will make Egypt great again.” It is also a narrative that is equally promoted by the nostalgic public (especially manifested in social media through sharing of black-and-white images of a “cosmopolitan” Egyptian imaginary) as condemnation of the regime for having failed to care for heritage and culture.

The narrative is reinforced daily by the faded grandeur of buildings that remind you of their Italian architects. Or the conversations of older-generation Egyptians from an urban center who would have at least warmly recollected one Italian friend growing up, before they disappeared in the trenches of Nasser’s nationalization policies. In short, there is a lurking pro-Italian sentiment that is invoked by their presence in a past imagined to be more glorious.

“I always felt that being Italian in Egypt gave me a huge advantage,” says Alessandro Accorsi, an Italian journalist from the Marche region. “It helped me deal with policemen, government, people in the street. Egyptians love Italians — there’s a sense of brotherhood between the two countries, and I think we are also perceived as ‘less threatening’ than other countries from a world politics/power perspective.”

While this is a sentiment expressed by Italians in Egypt, it was also subjected to manipulation by the state, which used statements like “but we love Italians” in a frail attempt to evade responsibility. Regeni’s murder undermined the relative safety Italians have long enjoyed in Egypt. No one is off-limits in an insecure security state.

Sorbera acknowledges that the distinct relationship is quite a popular notion. “We share many experiences in terms of popular culture, a patriarchal structure of society and the history of cultural production — let’s think about cinema, for example.” However, she cautions, especially in light of Regeni’s death, this is partly a mystification, as “Italy and Egypt occupy two different positions in the geopolitical Mediterranean and global system, and Italy is certainly not a police state in which hundreds of people are disappearing.”

Other Italians do not necessarily view the situation through this lens, and echo statements one also hears from some French and Greeks. One tells me, “While authoritarian neoliberal control through violence and torture takes place in Egypt, in Italy it happens through deprivation of basic rights.” Egypt’s unabashed violence and lax rule of law cannot be compared to Italy’s, but there is a unique experience Italians seem to undergo that can act as a powerful catalyst for them to move to and emotionally invest in Egypt.

The issue has, in part, to do with a number of faceless and predatory Italian corporations that have a stake in North Africa, especially Egypt. When the chief of Confindustria (Italy’s national chamber of commerce) stated a few years ago that the southern Mediterranean is our China and should be considered as our main market and commercial partners, his statements raised concerns and masked a darker narrative. As Omar Robert Hamilton has argued, Italy is implicated in Egypt’s violence: from Italian company Iveco, which exports police trucks that ran over Egyptian protestors, to weapons company Fiocchi, which contributed the bullets that ended the lives of countless peaceful protestors. This is just a small part of the story of Italian companies invested in Egypt’s economy of violence — the very system that enabled Regeni’s death.

However, Italian activists, journalists and academics are, in fact, extremely critical of this neoliberal global order. Their support for Egyptian struggles for justice is an extension of a deeply anti-Italian establishment position.

“In some ways, [Egyptian president] Sisi and [Italian Prime Minister] Matteo Renzi are not any different,” says Azzurra Sarnataro, a researcher from Naples who works on community development in Cairo’s informal areas. “I stand against Sisi in the same way I stand against Renzi and his political and economic policies.”

By understanding this line of thinking — commonly expressed in different words — it becomes clear that Italians in Egypt are partly projecting their anti-neoliberal grievances onto Egypt.

“Egypt has always been (and still is) an excellent laboratory where it was possible to observe the interplay of endogenous and exogenous factors, and their impact on politics and society … the setup of power games on an ideological and religious basis, and the exposure of conflict of interests and the corruption machine,” says Chiara Diana, a researcher from the Campania region who writes on the post-revolution’s political socialization of Egyptian children.

Accorsi notes that he felt the Egyptian struggle was his struggle: “Egypt gave me an ideological space that I couldn’t find in Italy, exactly because the [Egyptian] revolution happened at a time when Italian social movements were living a general crisis and political apathy was reigning sovereign.”

Sorbera offers a more tempered view, saying, “Being away from home always provides a different — and I would say productive — space to articulate a more nuanced awareness of oneself and others.”

On the other hand, expanding on Accorsi’s view, Diana argues, “I think there is currently an ideological and political flattening in Italy that monopolizes citizens’ attention on issues such as security, terrorism, protection of national territory and culture. This prevents them from addressing problems related to their daily struggles, like the economic crisis or budget cuts in social welfare and education. In this way, there is the potential risk that those fundamental struggles take a back seat, while discrimination, fear, self-sufficiency and nationalisms lead the field.”

This, she states, is where Egypt breaks the morbid status quo. “In Egypt, the subalterns’ demands for human rights, social justice and freedom allow people like me to continue to believe in the dignity of human beings and in the struggle for their rights.”

While it might not be unusual to find such views in other Western nationals, the Italians stand out due to the more historically, socially and geographically intimate approaches they take toward the Mediterranean and Egypt, which can be summed up by what an Italian professor at the University of Bologna told his class: “The issue is not whether Turkey or Israel should join the European Union, but whether Italy should join the Arab League.”

Italy is also witnessing growing anti-Arab and anti-Muslim xenophobia, tied especially to the refugee crisis. But it’s not the bigots who are choosing to head south — those who follow an idealized line of thought from the peninsula’s base are crossing the sea because of such a perceived affinity.

“Many of us believe in the Mediterranean Sea, both as a space of historical and cultural bonds and a privileged space to express dissent,” says Enrico De Angelis, a scholar on media studies from Naples. “Italians complete their collective identity with the southern coast of the Mediterranean, and look to the south as they look to the north.”

“I feel a human proximity with Egyptians concerning some fundamental struggles, such as dignity of life, social justice and guaranteeing of basic human rights. Why this proximity? I don’t know, maybe because I come from the south of Italy, where social conditions are sometimes hard, like in Egypt,” Diana says. Sarnataro is more adamant, saying, “We as southern Italian, even those among us who are not politicized, share with Egypt an understanding of economic difficulties.”

Yet De Angelis takes exception toward such a widely held view, and states, “This can be a distortion due to the fact that we have regular access to some parts of Egyptian society and not all of it. There is a big difference between Italy and Egypt economically. Maybe you can say that the struggles against neoliberal policies can be the same, but from different positions.”

Nonetheless, what emerges across the board is a distinct southern Italian identity harnessed to building a bridge to North Africa. This is further legitimized by the fusion of the North’s anti-southern discrimination and anti-Arab racism, which was conveyed to me by an Italian professor from the University of Cà Foscari Venice, through the use of a 1960s Italian joke: Sicily is the only peaceful Arab country, as it has not yet declared war on Israel.

This is not to suggest that Regeni is a product of all the aforementioned factors. In fact, he left Italy at the age of 17 — a decade before he was murdered. Nevertheless, he was plugged into the Egyptian public sphere as an “Italian,” which came with the semiotics and social signifiers understood by the political, cultural, social and historical Egyptian matrix. Regeni’s gregarious personality, dynamic work and humane ideals — all within a “pro-Italian” environment — may have helped him until the illusion of immunity was shattered. It has “made us all equal in fear,” says Francesca Biancani from Bologna, a scholar on Middle East history with a focus on colonial Egypt.

Given their long and intimate experience with Italian activists and socialists over the years, it was not surprising that Egyptian revolutionaries circulated the hashtag, “Giulio is one of us and died like one of us.” Just as Rachel Corrie was adopted by the Palestinian cause, Regeni is possibly the first non-Egyptian to be inducted into the Egyptian revolution’s narrative of martyrdom. This was the first attempt to challenge the equation of citizenship and loyalty. That a member of a transnational community can also exhibit an equal, if not stronger, loyalty to Egypt’s public welfare is telling.

Regeni’s death, as Biancani notes, “could also be a promising new start for a wider struggle, really linking young generations with the same sensibility on both shores, as it seems to me that the way those in power are going back to utilizing very coercive forms of domination — almost anachronistically — is happening everywhere with varying degrees.”

The autobiographical novel by Italian writer Fausta Cialente, Le quattro ragazze Wieselberger (The Four Wieselberger Girls), is perhaps telling of the vision of Italians preoccupied by Egypt today. In 1922, Cialente witnessed a fascist parade underway from Milan to Rome. She responded by wanting to go back home to Alexandria in a “Middle East, all open, where freedom for us Europeans was full and pleasant.” She would later move to Cairo to air anti-Mussolini and anti-fascist propaganda over the radio.

The Italians who are preoccupied with Egypt today possibly see elements of Italy’s fascist past in the present world of Cairo and Alexandria — the cities that once offered them political safety and tolerance are now increasingly exhibiting the fascist tendencies ominously narrated by their grandparents. The road linking the two cities became the transitional cemetery to Regeni’s body when it was found dumped on the Cairo-Alexandria highway.

For Regeni, it seems to me that it was never just about writing a dissertation — tumultuous Egypt was the place where, as a student, his political identity could flourish through imaginative ways it could not back in Italy. It is where his “vision of reality” could be enriched and fulfilled. Like many of Italy’s youth who see their upward mobility hampered by nepotism, Regeni could, at the very least, “develop his sense of being a global citizen,” as Italian journalist Paola Caridi writes on her Invisible Arabs blog.

Maybe no one could better express Regeni’s vision more profoundly than his mother, Paola Regeni: Giulio was “an Italian citizen, a citizen of the world who could have helped many people in Egypt and the Middle East. He had foresight, that’s why he learned Arabic and was so interested in economics … [and] marginalization … He did not go to war. He was not a journalist. He was not a spy. He was a contemporary young man of the future who was studying. He went for research, and he died under torture.”

What response can be given when Regeni came to Egypt full of idealism and selflessness to understand the poor and downtrodden, only to tragically meet a fate not unknown to them?

I cannot think of a sentence that captures the monumental moral crisis that Egypt is faced with like this one by Regeni’s mother: “On his face, I saw all the world’s evil poured on him.”

Paola Regeni spoke from the other side of the sea. She held up a mirror toward Egypt and said, “What is happening now should make us all think about it. We lost Giulio, but many others ended up the same way as Giulio. So he might be an ‘isolated case’ for Italian history, but not if we look at Egypt and other countries.”

The mother of Khaled Saeed — the 28-year-old Alexandrian whose death under police custody in 2010 helped incite the Egyptian revolution — responded in kind. “I want to thank you for standing with us, and that you care about torture cases in Egypt,” she said.

In a coffee shop across the Alexandrian Corniche, a man asked why Italy is still making a fuss about Regeni. A patron stood up in the corner and yelled, “Because that’s what it looks like when a country actually cares for its own citizens.” An eerie silence followed. An evocative reminder why, some 50 meters away from the same coffee shop, Khaled Saeed was killed by two police officers almost six years ago, and his death mattered then — surely mattered enough for a revolution to be sparked. The same revolution’s fifth anniversary that saw Regeni go missing.

In the same anti-fascist spirit that Cialente wrote about in the 1920s, Regeni was, in a sense, a witness and warning siren, a harbinger of the rise of unaccountable rulers and the erosion of freedom, rights and human dignity. For that reason, among many, Regeni’s coming to Egypt was never in vain, and neither was his final departure.

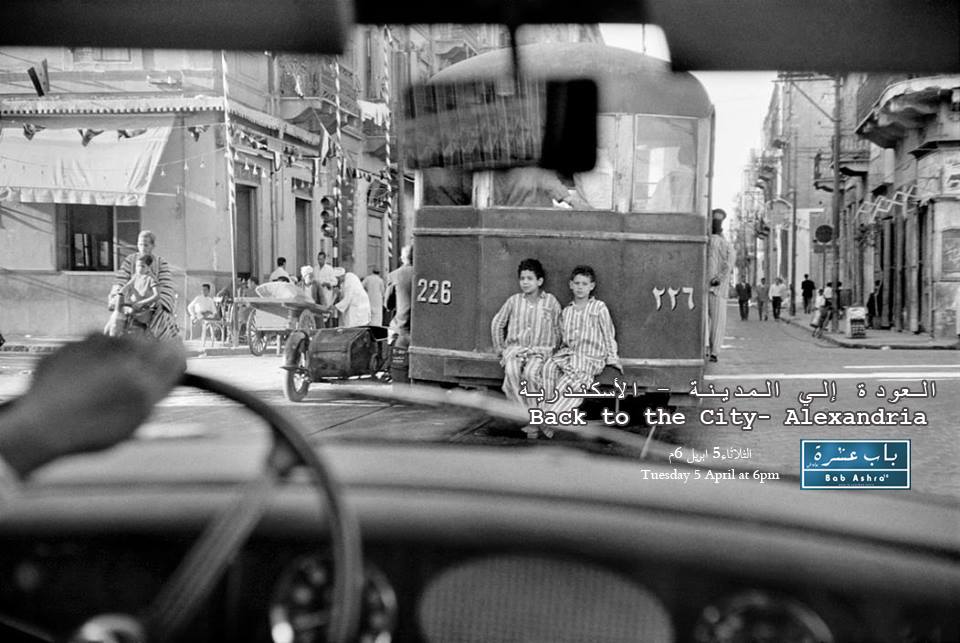

Back to the City: Understanding Alexandria’s Historical Awareness of Civic Responsibility

I will be giving a talk and holding a discussion that seeks to understand how historical and philosophical processes shape the Alexandrian citizen’s relationship to identity, spaces and history. The session will raise questions of how does one improve their relationship to the city in a climate of indifference and apathy? How is greater meaning attained, beyond food and work, when mediocrity is on the rise? How does one set a counter-example when things around – from architecture to basic aesthetics – appear to be getting worse and ugly. The talk is to initiate a conversation on what challenges prevent such questions being raised and enacted, and what dimensions of Alexandrian society hampers social and civic progress.

This talk will be in Arabic

Date: 5 April 2016

Time: 6pm

Venue: Bab Ashra, Alexandria

Facebook event page

Free admission and open to the public. As seating is limited, please register by sending a message with your name and mobile phone number to Bab Ashra Facebook Page

more info :

03/5754917 – 01220841384 – 01223541065 – 01211624006

www.facebook.com/bab.ashra

bab.ashra@gmail.com

Address : Janaklis ,abuoker .. mortada st. Elkhalig tower entrance G ..first floor

العودة إلى المدينة

عن فهم تاريخ الوعي بالمسئولية المدنية في الإسكندرية في إطار تاريخي

هذه المناقشة تسعى إلى فهم كيف شكلت العوامل التاريخية والفلسفية علاقة المواطن السكندري بالهوية والمساحات والتاريخ . كما انها تثير عدة أسئلة منها: كيف يمكن للمرء تحسين العلاقة بينه وبين المدينة في جو من اللامبالاة و الفتور ؟ كيف يمكن التوصل الى معان أسمى للحياة تتخطى الأكل والعمل في حين أن الاعتيادية في ازدياد ؟ كيف يصبح الانسان نموذجا للمقاومة عندما تكون الأمور في جميع النواح – من العمارة إلى الجماليات الأساسية – تزداد سوءا و قبحا .

المناقشة تأتي لبدء حديث عن التحديات التي تحول دون اثارة مثل هذه الأسئلة، كما انها تضم الأبعاد المختلفة في المجتمع السكندري التي تعوق التقدم الاجتماعي و المدني .

نأسف لمحدودية العدد نظراً لسعة المكان , لراغبي الحضور ارسال الأسم ورقم الموبايل علي :

https://www.facebook.com/

لمعلومات أكثر:

03/5754917 – 01220841384 – 01223541065 – 01211624006

www.facebook.com/bab.ashra

bab.ashra@gmail.com

أو التوجه مباشرة الي مقر الأتيليه :

637 جناكليس شارع أبو قير ,شارع مرتضي , برج الخليج مدخل “ج” الدور الأرضي .