“Stupidity does not consist in being without ideas. Such stupidity would be the sweet, blissful stupidity of animals, molluscs and the gods. Human Stupidity consists in having lots of ideas, but stupid ones. Stupid ideas, with banners, hymns, loudspeakers and even tanks and flame-throwers as their instruments of persuasion, constitute the refined and the only really terrifying form of Stupidity.” – Henry de Montherlant, Notebooks, 1930-44

How and why did a word so relevant for our times be pushed almost to oblivion? In a world where stupidity penetrates multiple levels of government, policies and personalities; it is strange that the term coined to best describe it has actually ended up in the endangered and forgotten words books. Stupidity in governance needs to be treated as a political problem, and kakistocracy can best capture this problem.

Kakistocracy is the government of a state by its most stupid, ignorant, least qualified and unprincipled citizens in power. Kakistos means “worst” which is superlative of kakos “bad” (perhaps also related to “defecate”). Along with kratos (see -cracy) meaning “power, rule.”

The first documented example appeared in 1829 in a book called The Misfortunes of Elphin, written by the English novelist and poet Thomas Love Peacock.

They were utterly destitute of the blessings of those “schools for all,” the house of correction, and the treadmill, wherein the autochthonal justice of our agrestic kakistocracy now castigates the heinous sins which were then committed with impunity, of treading on old foot-paths, picking up dead wood, and moving on the face of the earth within sound of the whirr of a partridge.

By 1876, the American poet James Russell Lowell was clear regarding its political implications when he wrote in a letter:

What fills me with doubt and dismay is the degradation of the moral tone. Is it or is it not a result of democracy? Is ours a “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” or a Kakistocracy, rather for the benefit of knaves at the cost of fools?

Yet given the prevalence of the problem it describes, the word is strangely not appreciated and underused in the twentieth and twenty-first century. The University of Sydney library search shows, since 1917, a modest use of the term only to suddenly peak after 1981. Perhaps because it corellated with the rise of neoliberalism which has an intimate relationship with stupidity, or to put it more harshly in the words of Mexico’s Subcomandante Marcos: “Neoliberalism is the chaotic theory of economic chaos, the stupid exultation of social stupidity, and the catastrophic political management of catastrophe.” Kakistocracy as a term then tapers off only to make a modest rise around 2008, when eight years of Bush hinted the word might be of some significance. Yet by rise, I am speaking of less than a dozen texts. Overall, Google Scholar sees the word employed merely 204 times in the scholarly literature. A few reasons can explain this neglect.

First, the heavyweight dictionaries have not come to a consensus on the term – Merriam-Webster and Collins list kakistocracy, but Oxford and Cambridge do not. Also there is little sign the term has spread from the English language (apart from its Greek roots) and made inroads into other languages – This could have ensured its widespread use.

Second, according to Phrontistery, there is a staggering 169 forms of governments, including bizarelly enough, diabolocracy (government by the devil) and pornocracy (government by harlots). I guess it must have been an issue at some point in time for someone to invent such terms. But it means kakistocracy is in competition with other robust and not so robust terms – creating an etymological dystopia.

Third, kakistocracy can be abused. It is not difficult to fathom from historical texts that every generation seems to consider their government as being the worst ever kakistocracy. The term is invoked to tarnish any government one does not agree with – acting as nothing more than a sophisticated guise for unwarranted attacks. There is even a risk the term could become too “mainstream,” losing its meaning and impact similar to the fate of, for example, soft power.

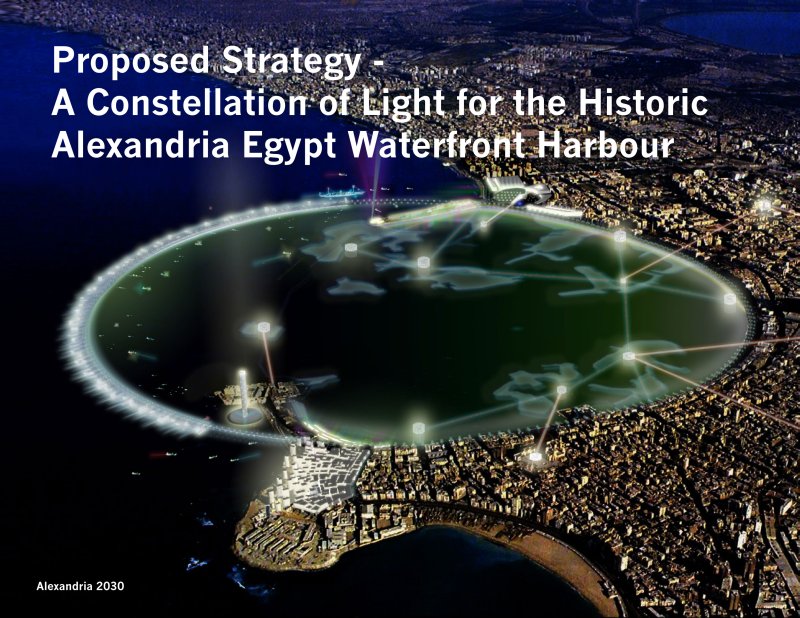

Finally, it is my suspicion that analysts have preferred to use kleptocracy (rule by thieves) instead. But kleptocracy is not the same as kakistocracy: They do both capture the element of least qualified or the worst, but with different meanings. Taking a reductionist stance for the sake of making the point, Putin’s regime is more of a kleptocracy, a regime ruled by thieves and thugs but that does not mean Putin is politically incompetent or stupid. Sisi’s Egypt shows elements of kakistocracy where stupidity is clearly characteristic of the personalities and decision-making process. This I have examined in detail in last year’s piece Egypt’s long walk to despotism that attempts to make sense of the relationship between Egypt’s political order and the stream of abusurdies we have witnessed over the past few years. Yet both Egypt and Russia share elements of kakistocracy and kleptocracy. There is no mutual exclusivness and clear demarcation lines in this debate.

Yet the flipside of not enganging with kakistocracy has left the word to the mindless circulation of memes and right wing shrills like Glenn Beck who sporadically employ it (and mispronounce it) to attack the Obama administration. Love him or hate him, Obama and his administration is far from anything resembling a kakistocracy. Bad decisions are not always a sign of kakistocracy.

Some might argue kakistocracy is a form of tautology, that stupidity can be rife through established democracies and dictatorships without needing to resort to a special word, or that behaviour is not enough to explain governance. I would argue otherwise: words matter, as a more sophisticated approach in the use of kakistrocracy, even if endowed with new meanings, can bring in a sharper conceptual understanding of incompetence, help provoke thought and new approaches to the relations of power.

Therefore, kakistocracy will not only capture rule by the “stupid” and the “worst,” but how they push human relationships, that form the controlling governmental machinery, into a degenerative state. The term will be more receptive to seeing a movement of ideas from psychology and sociology into the political science and international relations field. It will provide an organising concept to converse with its established kinfolk in the form of anti-intellectualism, mediocracy and nepotism.

To my knowledge, we are not even at the stage of seeing conferences on the dynamics of political stupidity, nor understanding the accumulative processes over the years that have brought about a large number of kakistocracies and stupidity as the standard bearer across much of the world.

Either kakistocracy gets used and thoroughly examined or a Trump presidency will force us to do so.

Update: Two worthwhile comments regarding this post come from Marco Lauri (Facebook). The first better explains the term pornocracy and the other proposes one way of sharpening kakistocracy.

“‘Pornocracy’ is a term with a long and very respectable history – used, I think, first in the Renaissance to describe the role of concubines in the running of the affairs of the Papacy during the tenth century – of course it was derogatory and never actually intended to describe a form of government as such.”

“I think that “kakistocracy” should be reserved for systems that positively select for stupid people to be put in charge. This is historically irrespective of the actual form of government (the idiots may be either appointed by an idiot despot, or elected by a dumbed electorate, or forced through the ranks by a purposeful mob, etc.). However, I support the notion because there are arguably common factors worth studying that enable the selection of stupid people. Sycophants are probably the easiest element to see and explain, but not the only one. There must be a whole ecology of systemic political stupidity awaiting analysis.”

![[From Alexandria’s Stanley neighborhood: “The People,” the eternal cry of the revolutionary voice that would follow it up with “Demand the fall of [insert your current oppressor here].”](https://amroali.com/aspire/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/the-people-300x225.jpg)