My presentation “Before Borders: Pre-colonial routes and worldviews in the Southern Mediterranean” for the conference/workshop on perceptions of the League of Arab States.

Date: 17 December 2024

Organizer: AGYA / L’Université Privée de Fès

City: Fez

“Our inheritance was left to us by no testament” – René Char

“At my first sight of the Mediterranean world I realized that I had never known light before. I was from the world of darkness. London was not so bad, but the light of the northwest is a very dull light. The light of the Mediterranean held my eyes so I decided to stay for a time.” – Albert Hourani (1915-1993)

All my content related to the glorious Mediterranean Sea.

It was an honour to moderate the Port-City dialogues event between the scholars and writers of Alexandria and Marseilles, with Alaa Khaled, Mohamed Adel Dessouki, Anne Millet, and Philippe Pujol. We explored the role of port cities after empire, and how ports shape the identities of these two magnificent cities of the Mediterranean.

Date: 3rd December 2024

Organizer: French Institute Alexandria

City: Alexandria

Event link: https://www.facebook.com/events/2012594592549423

Date: 22 September 2024

Venue: Goethe Institute Cairo

Moderating Dr. Faouzia Zeraoulia’s lecture on knowledge transfer and colonialism in the Maghreb, with a focus on Algeria. We had a spirited discussion on how knowledge production was reshaped through Francophone and Anglophone colonialism in Algeria and Egypt. This was part of the conference, Knowledge Transfer: Interdisciplinary Approaches Between Arts, Science And Society organized by AGYA.

I was delighted to give a lecture and workshop for Turkish students and cultural workers as part of the Summer School at the Swedish Institute Istanbul titled: Remembering and Coexisting in Turkey and the Eastern Meditteranean. We focussed primarily on Istanbul and Alexandria, discussing how the latter has become a bellweather for the erosion of pluralism, and how Istanbul understands this “demise” of Alexandria, and the warning it serves it and other cities.

I will be giving a public lecture at Leiden University on 21 January 2022, titled “Alexandria: The far eastern capital of the Maghreb” which is based on the recent essay “Where couscous ends: Maghrebi routes to Alexandria.”

Time: 11am (Alexandria time) / 10am (Amsterdam time)

The zoom link can be accessed here and does not require registration.

This short essay originally appeared in the Madrid–based Fundacion Alternativas.

The modern history and contemporary nature of Alexandria is a brew of different identities that give off (or once gave) a distinct resonance: Mediterranean, Egyptian, Arab, African, Middle Eastern, Islamic, Christian, Jewish, Levantine, among others. But the one profile that emerges as rooted in Alexandria’s existential survival is the Mediterranean identity. Within a few decades, rising sea levels will inundate parts of Alexandria in what could be the start of history’s closing curtains on the 2300-year-old city. Along with political and institutional will, it is imperative that Alexandria’s relationship to the Mediterranean shifts its face from past and present towards the future and pushed further into a wider regional narrative.

Ask an Alexandrian what makes up their identity and the first word you will most likely hear is the sea. The sea is central to the popular imagination, literature, films, theatre, escapism, growing up, families, wedding shoots, and a street art that reflects the bond with the sea and its history and myths: mermaids, citadel, centurions, Alexander the Great, and lots of ship-themed graffiti. Right down to the common line “If I leave Alexandria, I will feel like a fish out of water.”

The long stretch of corniche and wave breakers have displaced the beaches as the dividing line, liminal space, and intersection between the public and the sea. Access to the corniche and the ability to see the sea is a continuing battle in light of the privatisation and “development” drive that has, in many cases, cut off the public from viewing the sea, let alone accessing it. Yet pockets of communal respite are to be found. At the outset of the pandemic, the corniche furnished many of Alexandria’s young with the newly discovered hobby of kite flying that became a unifying public spectacle as even street children could get access to cheaply made kites. I had never seen that high degree of elation induced by any activity before on the corniche in many years. Barely a month or so passed and the kites were banned by the government on the official reason that they were behind a series of accidents (which is a legitimate concern but outright banning is different to regulating). The kite had, for a moment, become a hovering icon that connected sky, sea, corniche, and public.

To speak of Alexandria in a regional narrative is nothing new. Since the 1990s, elite efforts have been made to reintegrate Alexandria into the Mediterranean imaginary – albeit a neoliberal one that succeeded its colonial predecessor. The government rehabilitated the façade of the city as several institutes directed energies to crystalizing Alexandria’s role in the Mediterranean world which included the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Anna Lindh Foundation, and the former Swedish Institute, along with various cultural centres and initiatives.

Yet an endeavor needs to expand the notion of the sea from one linked to the past that evokes nostalgia and childhood memories, as well as the present that touches upon romance, enchantment, leisure, and livelihoods, to a future where an apocalypse looms on the horizon. Not to terrify the populace, but rather to deepen civic responsibility – from anti-littering to reconsideration of investment decisions – as part of the fight against climate change that can complement the respective policy on the matter. As well as linking Alexandria to efforts made by other cities in the basin as part of an unfolding story that aims to rescue the historical hubs of the middle sea. However, short of radical adaption measures, it is Alexandria, the only major city in the Mediterranean, that is at the highest risk of being largely submerged by 2050. It is no wonder why popular Google searches for Alexandria in the context of climate change reveal bizarre questions such as “Does Alexandria Egypt still exist?” and “who destroyed Alexandria Egypt?” It is an omen the city can do without.

Time and again, events have shown that Alexandrian public engagement or interest, particularly among the young and students, in their city’s welfare is heightened when they feel the city is part of a regional or global story – whether it be visits by foreign heads of state, clean up campaigns, artistic troupes, or the Africa Cup. It is part of the conscious Alexandrian mode of living to make sense of the fractured present while living in the shadow of multiple ancestral giants. It is the “nature of identity”, individual or city identity no less, “to change depending on time, place, [and] audience.” In this case, the repositioning of Alexandria’s Mediterranean identity can no longer be limited to culture wars, Euro-centric elites, and postcolonial critiques. It is now a question of survival.

As I have argued before, the Mediterranean is a laboratory with natural demarcations, rich history, trade, and cultural ties that could enable “an overarching new Mediterranean narrative to be written through a series of conferences, symposiums, workshops and accessible publications” with the possibility of contributing to “animating forms of transnational citizenship, a project that builds a Mediterranean platform” that can construct a new narrative and social contract.

Alexandria needs to feel part of the neighborhood story and brought into a mission in which its fate is tied with the same menace confronting Beirut, Tunis, Tangiers, Barcelona, Marseilles, and the rest of the cities dotted around the basin. While many Mediterranean cities will suffer from rising sea levels to hotter temperatures, the menace is eyeing Alexandria with the utmost ferocity and has earmarked a swathe of the city to be turned into one large underwater museum. A rising sea level that will perhaps regurgitate onto the city’s future and permanently flooded streets the thousands of abandoned facemasks and lost kites.

This essay was first published in German in the Berlin journal Die Politische Meinung (PDF) under the title, Mediterran?: Eine Lebensart und das Phänomen der Entfremdung (“Mediterranean?: A way of life and the phenomenon of alienation”) and later appeared in the English edition of the same journal.

“At my first sight of the Mediterranean world I realized that I had never known light before. I was from the world of darkness. London was not so bad, but the light of the northwest is a very dull light. The light of the Mediterranean held my eyes so I decided to stay for a time.” – Albert Hourani (1915-1993)

Hearing the word “Mediterranean” can elicit metaphors of cruises, golden beaches, lush hills, and succulent cuisines. In fact, follow up Mediterranean by appending the words diet, sunset, and villa, among others, and you have already produced the mental image of a semi paradise on earth. Yet the so-called “Mediterranean lifestyle” is often a highly-charged romanticised product of western consumption habits, holiday brochures, and diaspora musings – with a heavy focus on Greece, Italy, and Spain with the rest of the other Mediterranean countries at times acting as background furniture. The lifestyle is habitually treated as a given – it evacuates economics, class, and gender, and presumes that geography is all that counts. I want to visit this idea of the Mediterranean lifestyle and broaden its meaning, to look at how modern alienation ails the notion of the Mediterranean lifestyle and how we can think of it beyond its olive oil coat of arms.

In the literature and popular culture, the Mediterranean lifestyle is mostly the domain of food consumption, followed by tropes such as laughter, simplicity, passion, pleasure, living the moment, and visiting family and friends. This is not to say that none of these can be true or one does not relate to them on some level, but an idealised Mediterranean lifestyle is a claimant to a shared identity and space which does not necessarily exist for many.

The Mediterranean lifestyle weds a collective imaginary with an individual identity to form outlooks, attitudes, social relations, and possessions. As a key marker of social geography, the sea is an integral piece to the mosaic of personal identity. Inhabitants of the cities dotted around the sea will have some conception of a lifestyle uniquely tied to the sea. This distinguishes their coastal metropolis as different or “privileged” by virtue of being by the water, even if they do not necessarily call it the Mediterranean lifestyle. Sitting on opposite ends of the basin’s shore, a Spaniard in Barcelona and a Palestinian in Gaza would understand the sea differently. It can be a poetical space or a tormenting space, but it can also be one of shared possibilities.

Retrospective of a wonderful sea

Yet it is one of the ironies that a beautiful basin can be made the least economically viable. The story is an all too familiar one. The newly-minted graduate in Alexandria that eats her last seafood meal with loved ones before rushing to catch the train to start her new job in Cairo; the Sicilian youth in Palermo that gives one last glance to the sea before migrating to the affluent north in search for work in landlocked Milan; the underemployed Greek man who leaves his homeland for the colder but prosperous lands of the EU; the young Lebanese woman who has for years worked in Beirut’s culture scene and has decided to leave for Montreal to start her PhD, not only for educational advancement but to acquire a western passport as a form of mobility and partial restitution justice in an unequal world. Over the years, you get the impression that no one seems to want to leave the Mediterranean, but they are given little choice. Short of family connections, viable monetary inheritance, access to meaningful employment, ability to save, marry and buy a home; a growing number choose to abandon a wondrous sea that does not deserve to be abandoned.

Historically, the Mediterranean is not without its darkness. It is the sea that saw millions of deaths and gallons of blood spilled over the centuries through empire building, colonial conquests, pirate raids, and two world wars that turned blue skies into recurring passages of grey. Not to mention today’s refugee who flees political persecution and economic destitution, and dreads the possibility that the sea might become his or her graveyard.

But history is not always a history of sorrow and despair. In the everyday spectrum of life, there was a time when the Mediterranean lifestyle was understood as part of the sacred route by a Muslim pilgrim from Tangiers crossing several cities of the Mediterranean to eventually reach Mecca. The traders from Venice and Damascus that intermingled at the port in Alexandria. The Syrian that decided not to leave Tunis after he married and settled down there. The aspiring scholar on the Libyan coast that goes to Al-Andalus to further their studies.

A distortion of time and space

This is not to engage in a past utopia but to highlight that mobility was much more frequent among key demographics that enabled a holistic approach to the Mediterranean unlike our modern era which is characterised increasingly by forms of alienation. To speak of a vibrant Mediterranean lifestyle today requires some contemplation on the missing human encounters and away from mutant capitalist discourse that treats individuals as commodities zapping between resorts for Instagram shots, and mostly by travellers from the global north.

The alienation, in part, commenced long ago when port cities fell out of fashion with the dramatic reduction in the use of sea travel and the rise of commercial airlines in the mid-twentieth century which meant a person can go from Athens to Cairo, bypassing Alexandria. The once demanding but rhythmic process of departure and arrival across the sea now took on a radical change in which the human being exited the terrestrial order and was now suspended above the sea and moving at high velocity across the skies. Time and space were not only distorted, but the traditional relationship between humans and sea became a form of alienation limited to touching or swimming in the waters of one’s respective city, rather than traversing it. The once familiar homecoming and farewell scenes at ports greatly diminished. Civilian travel by sea was now mostly restricted to trips of limited duration and environmental-destructive cruises.

The 1990s saw the revival of port or second cities, such as Tangiers and Alexandria, that became favourable to neoliberal trade and transnationalism which, unlike capital cities that heavily invested in national culture, favoured cultural experimentation given that it could also be monetised. But this new Mediterranean world fell victim to the Washington Consensus, northern European banks, privatisation, environmental damage, and debilitating strands of neoliberal modernity. The expression “I no longer recognise my city” became a frequent mantra of a new internal exile in the Mediterranean.

The other form of alienation is governed by the visa regimes and passport tyranny, especially for the southern and eastern shores. As I have written before, “no transnational Mediterranean project can materialize when one side faces insurmountable inequalities in partnerships, safety, movement, and engagements.”[1] While I was specifically referring to the notion of a Mediterranean social contract and projects, the absence of equitable passport and visa arrangements still has the effect of skewing lifestyles in the lands of the global south depriving them of meaningful travel, exposure, and growth in their own neighbourhood. This is not only obvious from south to north; an Italian national can visit the entire countries of North Africa and the Levant with little to no effort in terms of no-visa requirement or a cheap visa on arrival. The Egyptian national does not know this world, travel is possible but it comes at a high probable chance of rejection by the consulate. The postcolonial story is one of insecurity even towards fellow global south countries. The end result is that the Italian is able to acquire a developed acquaintance with the region which add layers to his or her understanding of the Mediterranean lifestyle while the Egyptian is trapped in a provincial dimension of what constitutes his or her idea of that lifestyle. The Mediterranean lifestyle is not just a social or economic question, it is in the end, a political one.

Perhaps the Mediterranean lifestyle needs an accompanying conversation on developing a Mediterranean philosophy, one that correlates and thinks with rising political thought and activities through a shared space beyond markets. Activists and organisations are glaringly aware of the inequalities and are endeavouring to revive some sort of philosophy or social contract grounded in human rights, climate change initiatives, backed by the pandemic-induced shunning of long-haul flights in favour of short trips. Yet as someone who has sat through numerous meetings at the institutional level to discuss subjects related to the Mediterranean, I would sometimes wonder where are we going with all this? Gianluca Solera, who has advocated for a “renaissance” of the Mediterranean, argued that institutions with a Mediterranean mandate suffer from “deleterious development ideas, the same void decision-making mechanisms, the same discriminatory interpretation of citizenship, the same lassitude vis-à-vis its founding values would be produced, in the middle of a crisis, which is, before being economic, a political and cultural one.”[2]

“Return to origin” myth

It is heartening that there has been a growing interest in the Mediterranean that has been driven by organisations, cultural currents, universities, and international bodies and this stems from the fact that the Mediterranean sells itself: it is a metaphysical blueprint and socio-geographical crossroads that furnishes centuries of civilisations, scholarship, trade, religions, philosophies, and marriages. In a sense, there is a “return to origin” myth that enchants even the coldest of cold international bureaucracies that deal with the Mediterranean subject. But the question remains, how to readjust the gaze at the sea that is often one of distortion? Exacerbated by the excessive focus on the securitization and the refugee crisis which does little to address the alienation question. A democratic bottom-up approach is needed to marshal the thousands of initiatives that are taking place, stories told to one another, theorizing through the nights, workshops and training, and solidifying grassroots networks across the basin in what Solera has dared to deem a Mediterranean “Shadow-government.” I was at a meeting in Brussels, at the Friends of Europe summit, in 2019 where there was even talk of a “talent passport,” which still came across as problematic, but at least the question of global south mobility was being recognised and was pushed by activists and cultural workers. Still, there is a long way to go, many conversations to be had, and difficult questions to be addressed.

A depoliticised Mediterranean lifestyle should be respected, but we should also allow its political counterpart to show another way out of the alienation abyss. As it stands, the Mediterranean lifestyle is an indeterminate, fluid, and elastic conception that means different things to different people, yet is bounded by the natural demarcations of an ancient sea that sees an overlap of history, trade, tourism, cultural ties, and social justice within wider shared narratives. Despite the region’s cultural richness, the internal exile is a modern phenomenon of our time. Alienation, in the midst of underutilised cultural bonds, is a peculiar aspect of the modern Mediterranean lifestyle.

Passing by the wave breakers on Alexandria’s shore, I came across an impoverished boy gazing longingly at the sea. I asked him his name, he replied “Shaaban,” I followed it up with what his dream was when he became older, “to be a pilot.” I knew everything was stacked against his dream but I still told him “I hope you become a pilot, Inshallah.” He gave a big smile. These little moments in our Mediterranean world still matter.

[1] Amro Ali, “Re-envisioning Civil Society and Social Movements in the Mediterranean in an Era of Techno-Fundamentalism.” European Institute of the Mediterranean, Issue 25, Barcelona (2020).

https://www.academia.edu/49551586/Re_envisioning_Civil_Society_and_Social_Movements_in_the_Mediterranean_in_an_Era_of_Techno_Fundamentalism

[2] Gianluca Solera: Citizen Activism and Mediterranean Identity. Beyond Eurocentrism, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2017.

Alexandria’s connection to the Maghreb is often overlooked. But the cosmopolitan port city developed through centuries of migration and influence from the western side of the Mediterranean, up until the colonial era and the building of self-centered nation states.

This essay was originally published in Mashallah Magazine as part of the Mediterranean Routes series

***

“She is a unique pearl of glowing opalescence, and a secluded maiden arrayed in her bridal adornments, glorious in her surpassing beauty, uniting in herself the excellences that are shared out by other cities between themselves through her mediating situation between the East and the West.”

– Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta on Alexandria, 1326 CE.

***

It was always a quiet curiosity to me as a child in Alexandria that I would address my maternal grandfather as baba sidou when every other child around me referred to their own grandfather as gidou – the customary address to an Egyptian grandfather. It was only many years later that I discovered that baba sidou’s father, my great grandfather, was a Moroccan merchant who left northern Morocco circa 1903 to settle and marry in Alexandria, earning a living by importing goods from his homeland to Egypt. The title baba sidou, used to address grandfathers in some parts of northern Morocco, was a linguistic inheritance of an otherwise enigmatic heritage.

The memory of this form of address to my larger-than-life grandfather, Abdelmeged, was enough to spark an interest in attempting to trace the origins of his father. It also led me to widen my understanding of Alexandria in the great historical narrative of movements and peoples and the role of the Maghreb (here used in the classical sense to include northwestern Africa and Islamic Spain or Al-Andalus 711-1492 CE) in this spectrum.

The Maghrebi character of Alexandria is undeniable when you consider architecture, religious currents, philosophy and historical knowledge production.

The Maghrebi character of Alexandria is undeniable when you consider architecture, religious currents, philosophy and historical knowledge production. The city’s most prominent mosques and districts are named after medieval Moroccan and Al-Andulusian Sufi scholars including Sidi Gaber, Sidi Bishr and Shatby. It is, however, the iconic Abu Al-Abbas Al-Mursi mosque by the sea that stands out, housing the tomb of the scholar who gave the mosque its name. Born in Murcia in the south-east of Al-Andalus in 1219 CE, Al-Mursi moved to Tunis, then finally Alexandria, where he remained teaching for 43 years until his death. The white marble floor of the mosque, which was renovated and expanded over the centuries, underpins a cream-coloured structure with four domes that surround the octagonal skylight. The mosque itself was the inspiration for the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi which opened in 2007.

The Middle Ages saw Moroccan colonies emerge in Cairo and Alexandria, with the latter witnessing the construction of a madrasah for Maghrebi students founded by Saladin. By the late nineteenth century, the words jisr (bridge) and juj (pair or two) were frequently heard in the streets of Alexandria, meaning that either Moroccan Darija words had supplanted some Egyptian words in the Alexandrian dialect or it was simply a case of two dialects being spoken.

Why Alexandria?

The late Moroccan philosopher Mohammed Abed Al-Jabri notes a tradition in which the borders of the Maghreb “end where couscous ends, and couscous ends in the east in Alexandria and Upper Egypt.” Of course, Egypt historically has rarely been considered part of the Maghreb, which commonly ends at Libya at most. Yet the obscure tradition is quite interesting as it signals that distant Alexandria must have formed some reference point in the Maghrebi worldview.

The motives to make Alexandria their new home were quite evident. Mohammed El-Razzaz argues that the city was perhaps the furthest one could flee while still linking up to the familiarity of a multicultural harbour city. Alexandria was the last major port before heading to Mecca on the pilgrimage route. It had a vibrant merchant class due to, as the fourteenth century Tangiers-born explorer Ibn Batuta noted, its unique position of a “mediating situation between the East and the West.” In Alexandria, Maghrebi scholars could meet their counterparts from Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad and distant places. It is not difficult to see how couscous ended up as a dish being served in Alexandria.

“The Maghreb ends where couscous ends, and couscous ends in the east in Alexandria and Upper Egypt.”

The relationship between the Maghreb and Alexandria is not only old, it also had a dramatic start fit for a novel or film. In 818 CE Cordoba, an uprising that came to be known as the “Suburb Affair” took place in the southern impoverished district of Al-Rabad, across the Guadalquivir river, and was brutally suppressed by the Al-Andalusian caliph Al-Hakim II. Some 15,000 Cordoba residents fled the tyranny and, because they lived largely off piracy, sailed towards Egypt and seized Alexandria, turning it, in effect, into a city state. This was the first major case of re-immigration back into North Africa from Islamic Spain, including a smaller number that escaped to Fes. While it is possible the Cordobian exiles had local support at first, Muslim and Coptic sources speak of the cruelty that Alexandria endured under their rule. They were expelled a decade later by Caliph Al-Ma’mun when he reasserted his authority over Alexandria. The exiles then left and took over Crete. An indomitable bunch.

In one sense, the violent affair set the historical tempo of the Maghrebi resonance with Alexandria, which paved the way for a peaceful centuries-long story where merchants, travellers, pilgrims, exiles, scholars, philosophers and mystics left the Maghreb and the collapsing Al-Andalus and headed eastward to Alexandria and, at times, to the rest of Egypt. The Fatimid empire that sprung from Tunisia and ruled Egypt (969-1171 CE) facilitated one of the largest population migrations from Sicily (which was part of the Maghreb), Algeria, Morocco, Libya and, especially, Tunisia to Alexandria. The Valencia born Al-Andalusian geographer and poet Ibn Jubayr noted upon his arrival in Alexandria in 1183 CE the multitudes of Maghrebis arriving, and was mesmerised by the city: “We have never seen a town with broader streets, or higher structures, or one more ancient and beautiful … We observed many marble columns and slabs of height, amplitude, and splendour such as cannot be imagined … Another of the remarkable features of this city is that people are as active in their affairs at night as they are by day.”

Piecing fragments

On my first visit to Morocco in January 2018, I was trekking along the mountains of Chefchaouen when I met a farmer named Abdullah who narrated interesting local fables that dealt with Egypt, including one in which Pharaoh Ramses II gave Morocco its name, even while “he preferred to die in Egypt.” The Egyptian pharaoh holds an impressive grip over the Moroccan imagination as the epitome of all evil (I have discussed this in a 2018 photo essay). Fables go both ways. In Alexandria, an aging resident in 2012 told me a local legend of the ghost of Sidi Gaber, named after sheikh Jaber Al-Ansari, a scholar and shepherd who grew up in Al-Andalus shortly after the Islamic conquest of the Iberian peninsula and settled in Alexandria. In June 1940, his ghost saw the Axis warplanes approach as they were about to bomb the British military installations in the Sidi Gaber area. So as to protect his name-bearing Sidi Gaber Mosque, he waved the planes away and consequently – so the story goes – all bombs fell on the nearby Cleopatra Hamamat district in the first week of the campaign.

The oversupply of information and digital asphyxia has de-narrativised the Mediterranean.

These tales are frozen in time, as the routes that enabled them no longer emerge in today’s era of mass media and predictable tourism patterns. The oversupply of information and digital asphyxia has de-narrativised the Mediterranean as it no longer permits for the emergence of fables and an air of mystery to this world.

Land and sea hajj routes that for centuries were essential to the flourishing Maghrebi self-understanding have long since been replaced by air travel, bypassing the symbolically rich ports along the way, Alexandria no less. As Abderrahmane El-Moudden puts it succinctly:

“For many centuries, the pilgrimage caravan was the most important, if not the only, means of travel to the Holy Lands. On their way, Moroccan pilgrims were forced to cross the majority of Arab Muslim lands. This fact alone gives the Moroccan travels a complexity that is reflected in the texts and colours the perception of sacred space and time.”

The author hints at the slow lingering process and toil that came with travelling that carried a high risk of death but enabled the surviving returnees to retell their stories that were chiselled from, perhaps, the longest journey they have ever embarked upon. The idea of such deep and prolonged transcontinental experiences today collapses under the parochial weight of Egyptian and Moroccan nationalist narratives and their desire to demarcate borders, categorise populations, and restrict movements in a region once characterised by fluid boundaries and transnational migration.

The idea of such deep and prolonged transcontinental experiences collapses under the parochial weight of Egyptian and Moroccan nationalist narratives

Scratch the surface of many Egyptians and Maghrebis and you will find foreign links in their family tree. Nationalist constructs can get quite ludicrous if you really think it through. For example, for an Egyptian to claim descent from pharaonic Egypt is to make the impossible claim that the chain of one’s lineage was never “disrupted” in over 2000 years. It would also deny the history that saw movements of peoples including Arabs, Maghrebis, Al-Andalusians, Berbers, Ottomans, Jews and so forth that married into Egyptian Muslim families, or the innumerable Greek, Syrian and Ethiopian Christians that married into Coptic communities. This is not the same as making a cultural claim. One can certainly associate with and draw lessons from a country’s long history and rich traditions. But culture is often too lightweight a contender to the disturbing “races and blood” discourse even if these terms are not specifically used, but implied.

How it ends

It is probably worthwhile to capture a snapshot of the current dynamics between Egypt and Morocco. At the political elite level, tensions surface from time to time, given that Egypt faces a balancing act to placate Morocco and Algeria who have long standing hostilities with one another. In the media, attacks have taken place with a misogynistic stab.

In 2014, Egyptian presenter Amany Al-Khayat – spited by the Palestinian leadership’s appeal to distant Morocco, rather than neighbouring Egypt, for help during the war on Gaza – deried Morocco as a country with a “HIV prevalence rate” and an “economy of prostitution.”

This ignited a wave of anger from Morocco and sparked a diplomatic crisis; Al-Khayat later apologised. In 2020, Moroccan singer Ibtissam Moumni was outraged that Egypt cancelled a concert by fellow Moroccan artist Saad Lamjarred because of rape charges that he was facing: “You think that Saad Lamjarred will hold a concert and harass your daughters, who are like men.” This caused a fury on Egyptian social media and she later apologised on Instagram.

Yet policymakers, media pundits and celebrity bickering usually operate in a world away from coffeehouses, mosques and campuses. Interestingly, Al-Khayat and Moumni’s conciliatory approaches saw them appeal to both countries’ civilisations, rich heritage and intellectual traditions. This, incidentally, is how the countries’ publics view the other. When the former grand mufti of Egypt, Ali Gomaa, labelled the fourteenth century Granada-born Maghrebi scholar Imam Abu Ishaq Al-Shatibi (who is buried in Alexandria and has a major district named after him) as a mere “journalist,” Moroccan scholars were angered and launched a heated rebuttal at Gomaa. At least the once thriving medieval relationship still matters in some sense.

The current passport apartheid system have restricted meaningful mobility, preventing Moroccans and Egyptians from visiting each other freely.

But the above mentioned incidents pale in comparison to the greater tragedy of the North African story. The historical symbiotic relationship between Egypt and Morocco is not as flourishing as it once was. The francophone and anglophone colonial trajectories divided the Maghreb and Mashreq further. The current passport apartheid system, and visa regimes that prioritise EU nationals over someone else from the global south, have restricted meaningful mobility, preventing Moroccans and Egyptians from visiting each other freely.

Moroccans rarely meet Egyptians, which creates a vacuum that is filled with personalities and places like the pharaohs, Um Kalthoum, Abdul Basit Abdus Samad (a famous Quran reciter, 1927-1988), Al-Azhar, the pyramids and, undoubtedly, Mohamed Salah. Perhaps also comedian Adel Imam, who gets a disproportionate amount of attention and has skewed the image of Egypt like everywhere else. The decline of Egyptian soft power through film means that the Egyptian dialect is now understood mainly by the older generation of Moroccans. For Egyptians, the mention of Morocco evokes beauty, enchantment, religious heritage and kinship, with a sprinkle of celebrities or the talk of a recent football game.

For Egyptians, the mention of Morocco evokes beauty, enchantment, religious heritage and kinship.

However, regrettably, Egypt joins the rest of the Arab world chorus in never failing to note sehr (black magic) when the topic of Morocco arises. The idea is that Moroccan women are prone to employing witchcraft to cause some sort of harm to others. This can indicate why Egypt’s opposition media outlets were able to effectively spread the rumour – relying on dubious documents – that the current Egyptian president’s mother was a Moroccan Jew. Not only was there no factual basis to the antisemitic nature of this claim, it also says a lot about the function of Morocco as a distant and mysterious enough place to give the rumour an air of plausibility. The viral claim moved the Moroccan state to officially declare the documents to be a forgery.

On dying and rebirth

Towards the end of the conversation, Abdullah, the farmer in Chefchaouen, mentioned something that grabbed my attention. “A big part of our community migrated to the city of Alexandria over the centuries,” he said. I beamed with a smile.

Soon after, I came to realise that my great grandfather had dropped his Moroccan surname, making it difficult to trace his origins, and picked up an Egyptian name instead, Al-Fayoum, after the oasis town in Middle Egypt. Why he chose that name in particular I could only speculate. Given that it was part of a trade route, I would suspect that he had visited the town. One family tale says that he had fled a conflict taking place in Morocco, most likely the rebellion against the French and Spanish carving out colonial zones of influence in Morocco in the early 1900s. The name change may have been a way to evade the transcolonial collaboration across North Africa to arrest dissidents in distant lands. Additionally, the rising sense of Egyptianness at the turn of the century could have been an invitation for him to become part of the emerging national narrative. This was symbolically realised when he married an Egyptian woman named Baheya El-Sherif.

He knew I loved to go to the top and see my city from there, as if I was a low gliding bird.

My usual routine as a five-year-old in the 1980s was to go to see baba sidou after school. He would take me to the downtown area of Mahatet el-Raml and buy me popcorn or a sweet of sorts. On other occasions, he would wait specifically for the double decker blue tram as he knew I loved to go to the top and see my city from there, as if I was a low gliding bird. I would take out chalk from my pocket that I had snatched from the blackboard at school and start writing on the floor of the tram, both in Arabic and English, to the delight of the curious onlookers. One passenger told my grandfather that, “he will be something great in the future someday.” We would disembark in Azarita where he grew up, attend his favourite mosque for the asr (mid-afternoon) prayer, then he would go to the coffeehouse to meet friends and smoke sheesha while I played in the street in front of him.

This routine also included a visit with baba sidou to see his mother Baheya in the same area. Although her husband Al-Fayoum had died long before I was born, I was able to glimpse the last two years of her life, as a bedridden 95-year-old widow with her browned caramel skin drooping down gracefully. She had a certificate that qualified her as a midwife – I cannot remember if she hung it on the wall but she was extremely proud of the achievement – having received it at a time when education and qualifications for Egyptian women were hard to come by. A once outspoken wealthy woman who rose from the working classes, she ran coffeehouses and had her own horse-drawn carriage, but due to dwindling fortunes now lived in a tiny apartment. She died soon thereafter.

With his death, along with that of my great grandmother, came the end of one era as I knew it in Alexandria.

A few months later, her beloved son, the 69-year-old Abdelmeged – baba sidou to me – entered his beloved mosque in Azarita and, while in the kneeling position, passed away. The stoic worshippers shifted him so that he would lean against the wall, still kneeling, and then prayed over his body. With his death, along with that of my great grandmother, came the end of one era as I knew it in Alexandria. The time of seamless movement of personalities and their lives across the southern Mediterranean had dried up in the shadow of the mighty nation state and the hardening of borders.

My great grandfather, Al-Fayoum, who I know little about, became a sort of vector point. He left no photographs or written evidence – or I have yet to locate them – and thus I have relied on fragmented oral testimonies. My fickle memory of my dying great grandmother, a formidable Egyptian woman who married a stranger from the other side of the southern Mediterranean and edge of the Arab world, still lingers in my mind. Two simple words, baba sidou, encapsulates my own Egyptianness and sheds a new light of complexity on my Egyptian parents; one that is accomodating of complicated histories and sits well with my multifaceted Muslim, Arab, Egyptian, North African, Mediterranean, Alexandrian, and Australian identities.

Towards a reverse journey

In the summer of 2018, while in Alexandria, I made an error in my booking of a flight to Spain to attend a conference in Seville. I ended up having two tickets to Madrid that were non-refundable, but I could reschedule one of the flights. After the conference, I made my way to Cordoba and then to Granada. There was a restlessness to my presence in these two glorious cities. Cordoba is a place where you either find love or bring someone you love. In Granada, I stood before the gates of the Alhambra but could not bring myself to enter it. It is so majestic that entering it alone would have felt like selfishness.

The stopover in Casablanca had fate written all over it, as I had a chance encounter with a Moroccan doctoral researcher.

At the back of my mind throughout the trip was the costly accidental ticket. The rescheduled flight was for March 2019, a very inconvenient date during the teaching semester at the American University in Cairo. Since the airline would not allow me any later date, and because I was not quite yet in a holiday mood, I decided to pepper the trip with academic engagements.

The stopover in Casablanca had fate written all over it, as I had a chance encounter with a Moroccan doctoral researcher. After a week in Madrid, I booked my return flight with a three-day layover in Casablanca just to get to know this person better.

As we walked along the Casablanca shore one day, she narrated her life and showed me a black and white picture of her grandfather, a merchant riding a horse at the pyramids. She talked about her paternal ancestors, who were expelled from southern Spain in the closing curtain of the long Spanish Reconquista era, settled in the Moroccan port city of Tetouan in the fifteenth century and remained there until her great grandparents’ time. After that, the descendants migrated south. For a moment, I joked and wondered, what if Al-Fayoum had ever crossed paths with her great grandparents.

I told her that the hardest question I could ever be asked is “where is home?”

It was as if I was on the reverse journey of my great grandfather, or that of the Andalusian shepherd boy Santiago in Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist (in my defence, I was young when I read the book), who has recurring dreams of a hidden treasure at the pyramids of Giza. His journey across North Africa passes through the town of Al-Fayoum where he meets the alchemist and falls in love with a woman named Fatima.

The inquisitive researcher and I talked about the world and how I never knew a proper sense of home, having lived in several places. I told her that the hardest question I could ever be asked is “where is home?” She gave an evocative response that broke the long silence of my universe, “I will be your home.” Her name is Kenza, meaning “hidden treasure” in Arabic.

After a long series of obstacles, including a pandemic that is not kind to movement, we eventually married last summer. Hopefully someday, we can make it to Cordoba and, maybe, eventually cross the gates of Alhambra in Granada. Inshallah. For the time being, we will head to Alexandria, and do the ritual walk along the corniche until we arrive at the wave breakers along the Sidi Gaber shore, only to sit down, facing the sea, eating couscousy bel sukkar, sweet couscous cooked the Egyptian way with shredded coconut, butter, nuts, sultanas, cinnamon and hot milk.

***

References

Eickelman, Dale F (eds.) Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination Comparative Studies On Muslim Societies (1990).

Norman Rosh, A. M. R. (1994). Jews, Visigoths, and Muslims in Medieval Spain: Cooperation and Conflict. Leiden, E.J. Brill.

Razzaz, M. E. (2013) In the Footsteps of Mystics and Intellectuals: The Andalusi Legacy in Egypt Rawi Magazine.

Von Grunebaum, G. E. (1970). Classical Islam: A History, 600 A.D. to 1258 A.D. New York, Taylor & Francis.

Woidich, P. B. a. M. (2018). The Formation of the Egyptian Arabic Dialect Area. Arabic Historical dialectology: Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Approaches. C. Holes. Oxford, Oxford University Press: xix, 422 pages.

***

All illustrations for the Mediterranean Routes series were produced by Atelier Glibett in Tunis.

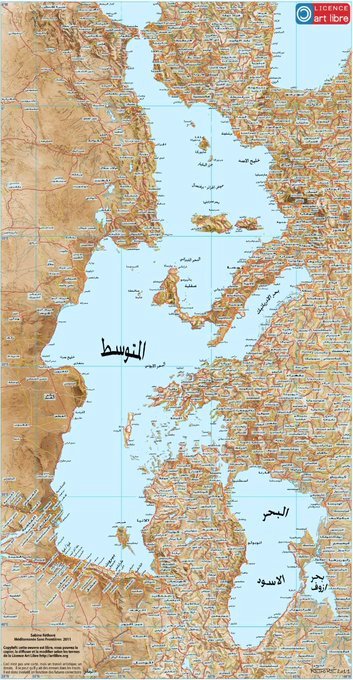

The “Mediterranean Without Borders” map was produced, in the political euphoria of 2011, by Paris-based artist Sabine Réthoré. Its profound simple 90-degree rotation not only underwrites an artistic streak, but can also largely impact one’s perspective. The end result is that the question is no longer about north-south as much as it is about parity and closeness. In the context of Mediterranean geopolitics, refugees crossing and drowning, fortress Europe, colonial history, skewed markets, condescending north to south (top to bottom) attitudes, post-colonial stagnation and so forth, means the simple rotation of the map is a big political statement with humanizing tendencies that make transnational ties look more intimate. That is an artistic statement in itself. This does not mean it will work for all maps, but it does so with the Mediterranean basin given the weight of its contemporary politics and long rich history.

The map was shown at an event in Brussels in November 2019, where I was invited to speak to EU and MENA youth, the opening was made by Marseille-based writer Mary Fitzgerald who presented this curious map of the Mediterranean rotated 90 degrees to the right. Fitzgerald provoked a lively discussion and the audience related more to the alternative map than its standard appearance. When I shared the image with others, it elicited various responses from it looking like a fantasy map to the humorous old woman trying to avoid stepping into the mud. Intimacy was a key response to the map. When I posted it to Twitter, geographer Joshua S. Campbell responded “Amazing how rotating a map changes your perspective. Maps tend to ossify spatial relationships in your mind…tweak the map, break the pattern. Also why spatial thinkers are useful, they possess the ability to rotate spatial relationships in their mind.”

What Réthoré’s artwork also does is furnish a metaphysical canopy to Gianluca Solera’s idea of transnational Mediterranean citizenship and breathes life into the dying political imagination. Solera argues

“the Mediterranean could become again a cradle of a new Renaissance if conditions were put in place for a project of transnational citizenship. A shared political initiative, putting together the various experiences of resistance, protest and popular alternatives, and building a Mediterranean platform for a new social contract, so urgent in times of profound crisis both in Europe and in the Mediterranean” (Solera, 2017).

Indeed, it may appear that we are a long way from this, but the grim reality of securitization, refugee crisis, and a pandemic overturning the world as we know it, can eclipse the years that saw thousands of initiatives taking place, stories, theorizing, training, in what Solera has deemed a Mediterranean “Shadow government.” Moreover, the region is moving towards a thinking in which the social contract will require rewriting as it faces the pressures of epidemiological threats, climate change, alarm at the dominance of big tech, to the receding of the long-haul flight in favor of local and regional travel, a travel bubble in some cases.

This is crucial if civil society, social movements, and transnational Mediterranean responsibility is to take on meaningful qualities towards how the digital order and terrestrial order are to be negotiated. Italian sociologist Franco Cassano noted:

“Unbridled technology does not signify the abandonment of earthy grittiness, but its perfecting it through the will to power. Mediterranean man, instead, lives always between land and sea; he restrains one through the other; and, in his technological delay, in his vices, there is also a moderation that others have lost. The unbridled development of technology is not tied to the crossing of land and sea, but to the oceanic lack of moderation, the chasing of the sunset by the sun, the absolutization of the West.” (Cassano, 2011).

In other words, the Mediterranean world is a philosophical gateway to deconstruct fundamentalisms as it has the “capacity to transform our limitations in a common benefit, a tragic memory in the fight against all forms of fundamentalism” (Cassano, 2011). Be it techno-fundamentalism or else.

The above is a short modified extract from my paper, “Re-envisioning Civil Society and Social Movements in the Mediterranean in an Era of Techno-Fundamentalism,” published in the European Institute of the Mediterranean (Barcelona). The journal article is open access.

My book review of Will Hanley’s work “Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria” has been published in the Mashriq & Mahjar journal (Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies, North Carolina State University). The PDF article is open access.

REVIEWED BY AMRO ALI, American University in Cairo

“Who are you?” is an all too familiar question in everyday life, one that is neither bound by time nor place, but can carry extraordinary consequences for the person being asked, and for history itself. It is a question that is central to Will Hanley’s outstanding book, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria, which illuminates Alexandria as a key sociolegal laboratory in the making of our modern world, covering the decades between the early 1880s and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. In this short pivotal span of history, Hanley telescopes into an enriching fusion of people from different countries who crossed each other’s paths on the streets, sidewalks, trams, trains, cafés, restaurants, and theatres. For many, the idea of personal identity revolved around timeless identifiers such as birthplace, religion, and marital status. They also had a nationality label but this, particularly until the 1880s, was usually a dormant, if not meaningless, category. That is, nationality suddenly meant everything when it became both a formal and informal requirement by the authorities or offered social and legal advantages.[1] That realization would bring people, and hence cement their cases on paper, to the police stations, consulates, and courts of Alexandria. The “wrong” nationality, like a Cypriot, could be a burden on the individual, while a privileged nationality, such as French or British, could mean protection from prison and access to wealth.[2] Egyptians, for whom the idea of nationality was yet to gain any social and legal coherence, were disgruntled at the nationality scourge that not only disadvantaged them compared to other nationalities, but the questionable court sentences and dubious acquittals also served to prove that the “outward garment of nationality concealed the domestication of the rule of difference.”[3]

Hanley’s book is divided into three parts, containing twelve chapters, an introduction, and an epilogue. In section one, “Settings,” Hanley illustrates the organizing concept of “vulgar cosmopolitanism” in chapter one. This concept drives the book’s key theme that shifts our familiar notion of Alexandria from a romanticized understanding and elite-centered cosmopolitanism to the mundane everyday life of Alexandria. The latter is where the matrix of passing, ignoring, jostling, and arguing occurs with habitual frequency until it crosses into legal territory, such as breaking the law, often lubricated by liquor and fomented by misunderstanding. Chapter two fleshes out keywords: national, citizen, resident, foreigner, and subject. The chapter aims to map out the book’s conceptual topology and the placement of individuals and their identities in the making of the emerging world at the turn of the twentieth-century.

In the second section, “Means,” Hanley scrutinizes the mediums of identification in the daily lives of society through the chapters of —“Papers,” “Census,” “Money,” and “Marriage” — which taught the population to identify with new labeling practices and familiarize themselves with a new vocabulary. The chapter “Papers” explores how passports and identification documents became the portable and impersonal means for the authorities to manage the mobility of individuals. While the chapter “Census” looks at the product of the state’s appetite to amplify its state-building project, negotiate disputes with diplomatic authorities over nationalities, and centralize the certification of identity. [4] The chapter on money fleshes out how currency became symbols for the emerging political and economic order and, hence, it required that tokens be honored. In light of this, counterfeiting was seen as an egregious crime, as it challenged the official order and the state’s power to circulate and monopolize symbols of value. The standardization of currency and material advantages sharpened the ability for nationalities to gain access to benefits and favorable rulings from judicial institutions that were predisposed towards wealthy national communities. [5] Finally, the last chapter of the section, “Marriage,” was a site of administrative anxiety given that nationality was largely a gendered practice by how easy it was for women to switch to their husband’s nationality or retain their father’s nationality through marriage, remarriage, separation, or divorce. But their transition depended upon the usefulness of the nationality in question, thus making marriage the “driving wheel of nationality litigation and legislation.” [6]

Hanley’s third section, “Other Nationalities,” spans six chapters: “Europeans,” “Foreigners,” “Protégés,” “Bad subjects,” “Ottomans,” and “Locals,” which takes up the larger essence of the book, as it seeks to map out the triumph of the nationality category, even with its precarities, over other markers of identification. Yet, Hanley takes us into a more complicated field beyond “powerful” Europeans and “weak” natives, as colonial privilege could not be easily deployed as distinctions were rarely obvious. For example, outside the small circles of European notables whom clearly had brazen privilege, poorer Europeans found themselves constrained by class, race, or gender.[7] Similarly, non-European foreigners like Tunisians and Maltese, who were imperial subjects, could exercise benefits in Egypt that were not possible back in their home country.

The case against Alexandrian cosmopolitanism that privileges elites and pioneers is certainly not new and has been fashionable in academic circles for many years. The author, however, gives the subject matter justice as he makes a strong case for shifting from the elites and small literary circles that intended to leave a legacy of written accounts, to the ordinary Alexandrians who did not. Thus, the book’s outcome is a one-by-one pointillist tapestry that draws you into a different Alexandria. Hanley argues against the proponents of triumphalist histories, writing, “We are not obliged to grant the nation the epic imaginary proportions,” and in making the case for the everyday ordinary, ironically, gives his work a distinguished epic of its own.[8] All accounts ended up in court and consulate documents, much like the recorded banal exchange between two Maltese friends, reading, “Today is Saturday, let us go and have a walk,” and ends with one friend fatally stabbing the other. [9] The dizzying number of accounts reads like miniature dramas with an endless cast of actors straddling the turn of the century, dazzling the city, and animating the era in fascinating ways. Taking the stage is the Cypriot realizing his Ottoman-ruled origins offered no protection from torture in a police station; the Egyptian woman who fell in love with an Italian man causing a scandal; the British consular official rushing to stop a marriage between a British Christian woman and an Egyptian Muslim man; an Irishman pretending to be an irrigation inspector to get a tasty meal and “borrow” ten francs from a priest; a French winemaker surprised that he would be imprisoned after he overestimated his foreign privilege by beating up an Egyptian tram conductor; And, eyewitness testimonies by Austrian barmaids pronouncing Islamic oaths. What Hanley’s book does is it upends what may have been thought to be established and predictable about nationality.

The label of nationality—the ever-recurring term that leads you through the book’s thematic kaleidoscope—creeps its way into the realm of individual identity, which was traditionally reserved for one’s name, occupation, place of origin, sect, and physical description. These attributes had to compete with “colonialism’s will to categorize populations and its pervasive expressions of power through small mechanisms and technologies and its modernity,” all of which were recognizable through nationality (though not the same as citizenship, which is a concept that would later become a key aim in decolonization movements).[10] This can be seen in Alexandria’s Maghribis up until the early 1880s, who were considered by local Egyptians as different, but not foreign. This invention of a nationality category, however, not only now made them foreign, but their status from a French colony also gave them further layers of protection (still short of the full legal protections that French nationals received) that unnerved locals, especially when nationality departed from the ordinary practice of the social into an exercise of its legality.

Identifying with Nationality is part of a trend that slowly crystallized in the mid-2000s and accelerated following the 2011 Egyptian revolution, which saw scholarship on Alexandria breaking the historical imperial-nationalist dichotomy that left little room for nuances. This shift took place amid a form of culture war between generations of Alexandrians, political positioning, and struggles to reconcile with the contradicting elements of the past. Perhaps beyond the book’s scope, it would have been worthwhile to give a brief analysis on modern Alexandria in the epilogue given the city was the ground zero and laboratory for the invented nationality category. Particularly because Hanley notes: “Alexandria was thus a bellwether for nationality changes that would spread worldwide in the twentieth century.” [11] As a resident of Alexandria myself, I wonder if modern Alexandria is a bellwether or troubling parable for the dysfunctions of nationality, as one sees the book’s longue durée projected into the present day as residents dwell on the debris left by nationality, nationalism, and an enduring colonial logic, which still scars Alexandria.

Hanley offers readers poignant lessons for our times, particularly given the triumph of nationality after World War I, which canonized smaller subsets of nationalities that we grapple with today, such as the “stateless, refugee, colonial subject, foreigner, and minority.”[12] Egypt’s Muslim-Christian relations, for example, were not without strain before the nationality category, but they were at least resolvable at the local level because differences were clearly known, understood, and mediated through a familiar pattern to the respective population center. Nationality, ironically, exacerbated religious tensions as it papered over differences and paved the way for state intrusion into local community matters. Even “Egyptian” did not hold much meaning for many Egyptians prior to the 1880s. The category only became important for bureaucratic reasons, not for membership of the watan (nation) or for paying homage to some pharaonic ancestry.[13] Rather, it was Egyptian elites who adopted the mantle of nationalism in order to wield “the resources of the state in their own interest” and saw to it that “nationalism expanded along the stolid avenue of self-interest.”[14] For the rest of the non-elite Egyptians, it would take decades to adopt the nationality label in any legal and nationalist sense. This reluctance can be explained, as Hanley puts it, because “the benefits of local status were often more obscure than its costs,” especially in terms of the burden of taxes and ruthless conscription, from which foreign nationals were free from.[15]

In traversing over four thousand cases, with over ten thousand individuals, and drawn from archives in five different languages from six different countries, Hanley delivers a superb piece of work in historical research, rethinking social history, and reevaluating national taxonomies, rather than assuming them. This book makes a significant and original contribution to the fields of transnationalism, citizenship, cosmopolitanism, comparative colonial studies, international law, Egyptian history, Alexandria’s urban history, and Mediterranean migration. It would appeal to both graduate students and scholars, but also to the informed public interested in these topics, as Identifying with Nationality, to its credit, does not intimidate the reader unfamiliar with legal jargon. The author has been merciful in making legal terms clearly legible, as well as subsuming them into captivating miniature narratives and vignettes that animate the sociolegal story of a bygone Alexandria. Therefore, it is not only a book that comprehensively adds to scholarship, but is ripe with countless gems to inspire future plays, poems, and stories.

NOTES

[1] Will Hanley, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 287.

[4] Ibid., 119.

[5] Ibid., 136.

[6] Ibid., 138.

[7] Ibid., 157.

[8] Ibid., 3.

[9] Ibid., 43.

[10] Ibid., 7.

[11] Ibid., 21.

[12] Ibid., 281.

[13] Ibid., 296.

[14] Ibid., 288.

[15] Ibid., 289.