I wrote a brief essay for the Forum Transregionale Studien on the techniques I undertook to teach sociology and philosophy to the Egyptian public and to elevate the agency of the audience members.

تجد/ين هنا النسخة العربية لهذا النص.

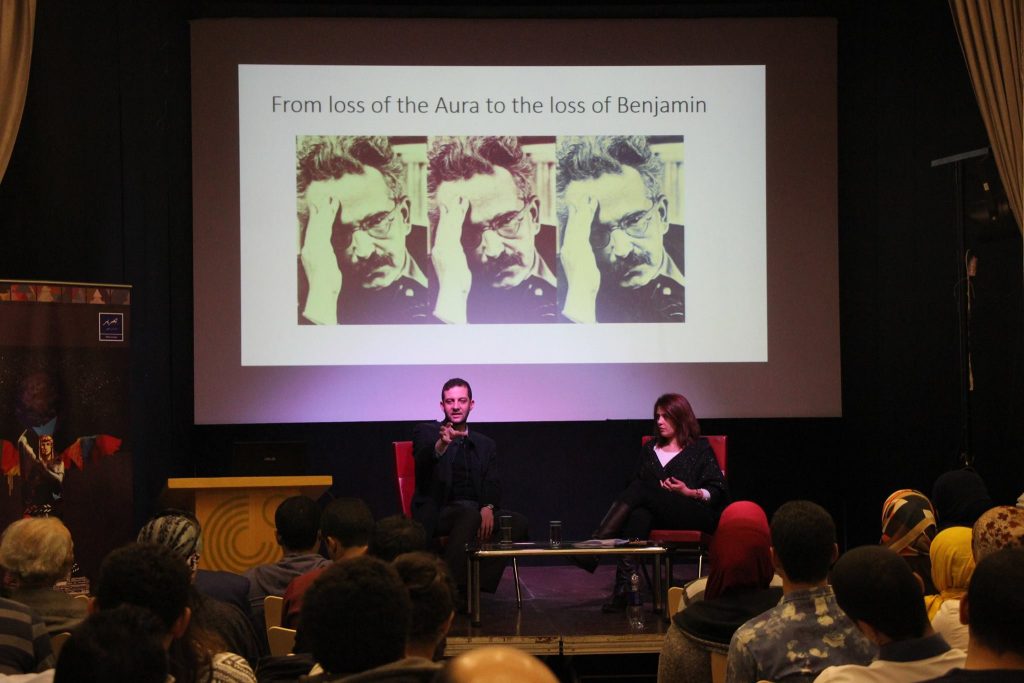

An enthusiastic Egyptian youth exited the closing of a lecture event in late November 2017 and rushed to a coffeehouse near Tahrir Square to meet up with his friends. He told them about this woman thinker called ‘Hannah Arendt’ who he just learned about and her peculiar idea of ‘new beginnings.’ Several nearby curious patrons overheard the chatter and enquired about the philosopher. The social circle widened, and the youth continued discussing the lecture that he had just attended. It would see some of the patrons coming to the next lecture session on Walter Benjamin’s loss of aura concept.

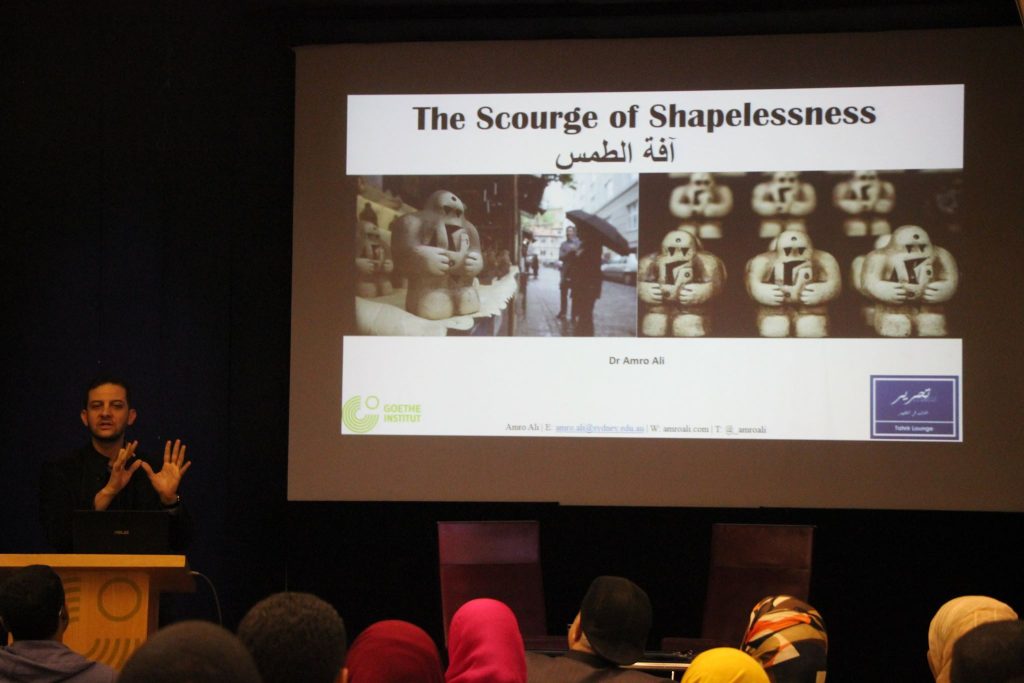

The youth had attended the first event in a long series of lectures and workshops (2017–2018) that I co-ran with Mona Shahien, the director of Tahrir Lounge Goethe, in Cairo, Alexandria and Minya, mostly in Arabic and some in English, that aimed to introduce philosophy and sociology to the Egyptian public in a comprehensible and practical way. I want to focus on the audience participant as an agent and I will outline, albeit not exhaustively, how the public teaching of sociology and philosophy can be merged with a certain structure, approach and content that elevates the agency of audiences. The project consisted of ten lectures; a workshop on Benjamin’s storytelling and aura, Arendt’s Vita Activa and Vita Contemplativa, and a theater play. I will focus mainly on the lectures as they were the primary thrust of the project and hold promise for academics, intellectuals and practitioners who seek to convey the ideas of the academy to the public.

The Theatre of Thought (not a theater as such but lectures) manifesto could be summed up as:

the public should be recognised, and elevated, as the primary ideal, and the individual’s present difficulties in experiencing or attaining pluralism and civic responsibility is tied to the city’s loss of meaning and the citizen’s alienation from one another. The development of philosophical thinking can help address this malaise.[1]

The project explored the notion of restoring the individual’s dignity and agency by ‘recalibrating’ them both to relate to the city. It raised the following questions: How can historical imaginaries, ideas, persons, sensibilities and aesthetics work their way into renegotiating the citizen’s relationship to the city? How can a crippling nostalgia be appropriated for a forward-looking civic vision? How do philosophical themes make one understand the familiar spaces, such as neighborhoods and coffeehouses, better? How can individuals and groups endow their urban terrain with a clearer identity and a relatively better coherent narrative? Does self-expression disguise a different set of established rules and practices in which nonconformity begins to look quite similar? How do we reconcile the digital order with the terrestrial order? What are the implications of perceiving the other, in terms of trustworthiness and reliability, when they are dissolved in a digital swarm?

It has been my long-running interest to merge the field of sociology and the ideas of philosophy to produce a particular type of discussion for Egyptian and Arab contexts. One way to do this was to approach an underdeveloped subdiscipline: Sociological philosophy. The American sociologist Randal Collins describes and validates this area as such: “[N]ormative self-reflection is a fundamental aspect of sociology’s scientific tasks because key sociological questions are, in the last instance, also philosophical ones” and “[i]f knowledge (or discourse in general) is social, then sociology should be in the most important position to reflect on the nature of philosophy as a form of knowledge or discourse.”[2] To put it another way, philosophy on its own is akin to the blazing sun, while sociology lends the shades that slightly obscure but reveal hues, tints, tones, tinges and contours of the philosophical subject. Philosophy in its ‘purest’ essence can be at high risk of handicapping itself from conveying ideas, making dense texts inaccessible and driving away readers and listeners.

Engaging Agency

Why would a university student in Assuit take the five-hour train journey specifically for an event in Cairo and return the same night? How do we end up with a peculiar scene of an Azhari scholar seated next to a worker from a jeans factory? The why question is critical to make sense of agency and what motivates people to come to an event mostly out of their domain of studies or usual interests. The answers to these questions were helped by the post-lecture conversations and the efficient feedback mechanism instituted by the Tahir Lounge Goethe. Part of the reason why the events could attract audiences was due to Shahien strongly believing in the project’s endeavor, prioritizing it, and putting resources into organization, promotion, and translation. In Cairo’s case, it was also helped by the venue, the Goethe Institute, being central and easy to reach by metro. Moreover, like all cultural spaces, there is often a significant number of returning audience members. However, there were overlapping and distinct factors that need further explanation.

The motives included many attendees seeking, to an extent, to compensate for a dysfunctional education system. For a number of young women from conservative families, the evening events were a way to justify their absence from home to gain extracurricular educational value. It was often some sort of dissatisfaction with the status quo as a sufficient underlying motive for going to these types of events. A number of audience faces at the start of the session revealed a weary gloom as if they had stepped out of the trenches of the suffocated public sphere. They did. The facial expressions are what one would expect after a two-hour long-winded session. Ironically, in many instances, it was the reverse in these events. Where frowns can also eventually turn to smiles. These places have become, in some sense, the last spaces of refuge from a public sphere that is increasingly criminalizing independent thought and non-officially sanctioned culture.

The audience participant’s voice and disclosure of identity was essential to their agency; the lecture often allowed a rolling conversation as the presentation unfolded. It was important to create sufficient breaks and meetings after the session, actively introduce members of the audience to each other and ask for their names. What may seem as banal or routine in any lecture event was often a profound experience for many of them. Some had never been in a situation at university in which their ideas were solicited or allowed to challenge the instructor. This was not unique to the project, but it did emphasize the importance of building a small community out of the sessions. The other approach to agency involved throwing down a challenge. Instead of me simply giving book recommendations, I asked them to head to the used book markets in Cairo’s Azbakeya or Alexandria’s Nabi Daniel street to engage with the books that seize their interest. Many did so. For some, reading a book after graduating from university was unheard of unless it was for work purposes.

The event always started with a powerful relatable metaphor. It would be the spearhead that set the tone for the lecture. Metaphors included, for example, the legend of Icarus, the Flying Dutchman and a vintage photo of a woman at the station waiting for the train. The metaphor when employed compellingly enabled the audience to project themselves onto the unfolding narrative of the night and add depth to the dizziness of their alienation, review their perception of social problems and kindle a reconstruction of imagination capacities needed for thinking through social and moral quagmires. It also helps to focus on the philosopher’s topic rather than the philosopher to avoid the problem of mini cults growing around the respective philosopher. This is why the philosopher’s name was not included in the lecture titles.

One of the hurdles can, at times, be dispelling the myth that philosophy is opposed to religion. This often needed to be discussed from the outset, and it helped by pointing out that Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali and Augustine of Hippo, among many others, were philosophers. A Muslim woman in a hijab in Minya said to me during the lecture break, “I had always feared philosophy as I felt it was atheist-driven, but I came to it through Kierkegaard because he was Christian.” This was interesting although not unusual. The religiosity of the philosopher or books that show a substantial overlap with faith made audiences highly engaged. Starting off with Arendt’s idea of forgiveness and briefly referencing Islamic and Christian texts on forgiveness, for example, helped to give the philosophical conversation a holistic formation and relatable intimacy without losing sight of the ongoing discussion.

Conclusion

This paper briefly examined the conditions and method of bringing sociological-philosophy to the Egyptian public, as well as the role of agency that engages audiences. I hope in future to expand comprehensively on the concept and look at class, social strata, generations, audience dynamics, content delivery, translation and the project’s successes and setbacks, among other factors.

Following the closing of the “Creative Public” session in 2017, a boy scout leader from the audience approached Shahien and said he wished he brought a 19-year-old boy scout he knew to these events. Shahien replied that he can bring him to the next session. The elder replied this was no longer possible as he had recently met the youth at a Cairo coffeehouse to discuss his future that would see him enter the college of engineering. During the chat, the waiter serving the coffee overheard them and stated that he himself had recently graduated from engineering. The prospective student was struck with horror that this could also be his future – serving coffee after completing some four hard years of engineering studies. Two days later, he committed suicide.

This tragic incident would shape successive events. Animating Spaces of Meaning sought responses to the rise of mediocrity and fragmentation of meaning that have become a familiar part of everyday urban life. It also elucidated that all study disciplines, professions and workplaces of all stripes can have their dignity, respect and even charm. Engineering and medicine should not be the only attainable routes to powered social mobility; the social sciences, arts and humanities, and any other stigmatized disciplines, for that matter, need to be elevated into highly respected areas of study. Conveying the sociological-philosophy lessons also means keeping a pulse on the lives and stories that the public brings to the sessions and then responding and shaping the following session accordingly. In some respects, it echoes Hannah Arendt’s personal axiom that “thought itself arises out of incidents of living experience and must remain bound to them as the only guideposts by which to take its bearings.”[3]

[1] Amro Ali, “When the Debris of Paradise Calls,” Amro Ali, 15 December 2017, https://amroali.com/2017/12/debris-paradise-calls-philosophical-concept-play/ [accessed 15 February 2021].

[2] Collins, Randall, “For a Sociological Philosophy,” Theory and Society 17/5, 1988, 669-702, 671. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00162615.

[3] Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977, 14.

This project is part of the activities of the Arab-German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanities (AGYA). The introduction to this blog series by Nuha Alshaar, Beate La Sala, Jenny Oesterle and Barbara Winckler can be found here.

Citation: Amro Ali, Bringing Philosophy and Sociology to the Egyptian Public, in: TRAFO – Blog for Transregional Research, 15.04.2021, http://trafo.hypotheses.org/28053