وُلد “علي” في الإسكندرية.. ونشأ في أبعد مدينة على وجه الأرض.. وأدمن الترحال بين برلين والدار البيضاء والقاهرة مؤمنًا بأهمية توصيل الفلسفة إلى عموم الجمهور

The writer Hany Zaied at the Scientific American magazine (Arabic edition) interviewed me through a photo essay on my academic life and how the tyranny of distance (Australia to Egypt) shapes one’s work, the role of bridging academia with the public, readapting sociology and philosophy into local contexts, why humanities and the liberal arts need to be made easily accessible to the public and made compulsory on the university level in the Arab world, and the importance of spaces and platforms such as AGYA, AUC, and FU. As well as why cities like Alexandria, Berlin, and Casablanca inform my activities.

تحكي الأسطورة اليونانية القديمة قصة “إيكاروس”، الذي احتجزه ملك جزيرة “كريت” –ومعه والده- في متاهة لم ينجحا في الهرب منها إلا بعد الاستعانة بأجنحة ثبَّتاها على جسديهما بالشمع، لكن “إيكاروس” –المستمتع بلذة تحدِّي قوانين البشر والطبيعة- رفض نصيحة والده بالابتعاد عن الشمس التي أذابت الشمع وجعلته يسقط صريعًا.

ظن “إيكاروس” نفسه إلهًا، متناسيًا وجود حدود فاصلة لا يمكن تخطِّيها بين البشر والإله! فالشمس التي اقترب منها تمثل الحقيقة والمعرفة، والاقتراب منها يحتاج إلى سؤال النفس عن عواقب الاقتراب من لهيبها، فهل يمكن أن تتحول أسطورة “إيكاروس” إلى مدخل لتبسيط الفلسفة؟ وهل يمكن أن تتحول صورة قديمة لامرأة في المحطة تنتظر القطار إلى مدخل لفهم الفلسفة؟

تلك الأسئلة وغيرها –على بساطتها- اختارها الدكتور عمرو علي -عالِم الاجتماع، وعضو الأكاديمية العربية الألمانية للباحثين الشباب في العلوم والإنسانيات، والزميل الزائر في برنامج “أوروبا في الشرق الأوسط- الشرق الأوسط في أوروبا” في منتدى الدراسات العابرة للأقطار في برلين- مدخلًا لتقديم الفلسفة وعلم الاجتماع للجمهور العربي بطريقة عملية ومفهومة.

يشبه “علي” علم الاجتماع بنظارة شمسية توفر الظل الذي يكشف تدرجات الموضوع الفلسفي وتلاوينه

نال “علي” درجة الدكتوراة من جامعة سيدني الأسترالية، وتناولت أطروحته دور الخيال التاريخي وتبدُّل الفضاءات العامة في الإسكندرية من خلال أعمال “حنة أرندت” و”فاتسلاف هافيل” الفلسفية، وحصل على درجة الماجستير في الآداب في دراسات الشرق الأوسط وآسيا الوسطى، ثم درجة الماجستير في الدبلوماسية من الجامعة الوطنية الأسترالية في عام 2009، وهو باحث في جامعة برلين الحرة التي تُصنف ضمن أفضل 10 جامعات ألمانية بشكل عام، وتتمتع بنقاط قوة خاصة في الفنون والعلوم الإنسانية والاجتماعية على مستوى العالم، ويعكف حاليًّا على إعداد كتابين أحدهما عن الإسكندرية والآخر عن برلين خلال إقامته القصيرة بمدينة الدار البيضاء المغربية.

يؤكد “علي” ضرورة الارتقاء بالعلوم الاجتماعية والإنسانية والفنون في المجتمعات العربية

شمس الفلسفة

يشاكس “علي” عقول مستمعيه وقلوبهم في ندواته وورشه بأسئلة مثل: كيف للخيالات والأفكار والأشخاص والجماليات التاريخية أن تعيد التفاوض بشأن علاقة المواطن بالمدينة؟ وكيف يمكن للموضوعات الفلسفية الارتقاء بفهم المرء للفضاءات المألوفة مثل الأحياء والمقاهي؟

يؤمن “علي” بأهمية العلاقة بين الفلسفة وعلم الاجتماع، مضيفًا في تصريحات لـ”للعلم”: الفلسفة تشبه الشمس المستعرة، في حين يشبه علم الاجتماع “النظارة الشمسية” التي توفر الظل الذي يحجب تلك الشمس قليلًا، ويكشف تدرجات الموضوع الفلسفي وتلاوينه ونبراته ونغماته وحدوده بما يساعد على نقل الأفكار إلى الآخرين، ربما بدا الأمر صعبًا، لكن حين يتحول عبوس الحاضرين في النهاية إلى ابتسام هنا تكون المكافأة.

اعتاد “علي” المشاركة في مشروع التحرير لاونج جوته بمصاحبة مؤسِّسة المشروع ومديرته “منى شاهين” في الفترة منذ 2017 وحتى 2018، تم تنفيذ المشروع في محافظات القاهرة والإسكندرية والمنيا، واستهدف تقديم الفلسفة وعلم الاجتماع للجمهور المصري بطريقة عملية ومفهومة.

إحدى ندوات “علي” ضمن مشروع التحرير لاونج جوته بمصاحبة مؤسِّسة المشروع منى شاهين

تُعرِّف منظمة “اليونسكو” الفلسفة -والتي تعني “حب الحكمة”- بأنها “ممارسة يومية من شأنها أن تُحدِث تحولًا في المجتمعات، وأن تحث على إقامة حوار الثقافات واستكشاف تنوع التيارات الفكرية، وبناء مجتمعات قائمة على التسامح والاحترام وإعمال الفكر ومناقشة الآراء بعقلانية، وخلق ظروف فكرية لتحقيق التغيير والتنمية المستدامة وإحلال السلام”.

الفلسفة والحياة

ربما دفعت تلك الهالة “علي” باتجاه دراسة الفلسفة والسعي إلى تبسيطها، مضيفًا: تَولَّد لديَّ اهتمام بالفلسفة في وقت مبكر من حياتي، وفي عام 2013 زاد اهتمامي بدراسة الفلسفة، قبل ذلك كنت أهتم أكثر بالعلاقات الدولية والسياسة وعلم الاجتماع، في ذلك التوقيت حدثت تغيرات كثيرة في مصر والشرق الأوسط، وهي تغيرات احتاجت إلى دراسة أكثر عمقًا لقراءة المشهد، ووجدت أن الفلسفة يمكنها تقديم صورة أكثر عمقًا ووضوحًا مما يبدو على السطح، في ذلك الوقت تعرفت على “حمزة يوسف”، الذي ينظم محاضرات دينية لا تخلو من الفلسفة في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية، علمني “يوسف” أن الفلسفة يمكنها أن تساعد في تقديم صورة أوضح للقضايا الدينية.

يقول “علي”: لطالما كنت مهتمًّا بالدمج بين حقل علم الاجتماع وأفكار الفلسفة للخروج بنمط معين لمناقشة الفلسفة وفق السياقات المصرية والعربية، أحببت الفلسفة لأنها تقوم على طرح الأسئلة دون فرض حلول، ومحاولة فهم تطورات الأمور، وهذا كان مهمًّا جدًّا بالنسبة لي، أقول دائمًا في محاضراتي إنك “لو لم تُفلسف، سيكون هناك شخص آخر يُفلسف لك”، الفلسفة مرتبطة بالحياة، لو جلست في مقهى، وشاهدت أشخاصًا يشاهدون مباراةً لكرة القدم وهم يصيحون، بينما يطالبهم شخصٌ آخر بالهدوء، فإنهم يردون عليه بأنهم يريدون مشاهدة المباراة، هذه هي “الفلسفة النفعية“، وإذا أخبرك شخصٌ بأنه سيذهب إلى الساحل الشمالي للاستمتاع بوقته، فإن هذا التصرف يدخل في نطاق “فلسفة المتعة”، الفلسفة مرتبطة بكل شيء نفعله حتى لو بدا هذا الشيء غير مرتبط بالفلسفة.

حواجز الخوف

يقول “ابن رشد”: يؤدي الجهل إلى الخوف، ويؤدي الخوف إلى الكراهية، وتؤدي الكراهية إلى العنف، وهذه هي المعادلة.

ربما صنعت مقولة “ابن رشد” أحلام “علي” ودفعته إلى كسر حواجز الجهل والخوف والكراهية والعنف عن طريق تبسيط قوانين الفلسفسة، مضيفًا: يجب توصيل الفلسفة للعرب والمصريين بأمثلة تتفق مع ثقافتهم، وحتى داخل الوطن الواحد يجب أن ننوع الأمثلة، بحيث نختار أمثلةً تتفق مع الطبيعة الأسوانية إذا كنا نتحدث إلى أشخاص من أسوان، وأن ننتقي أمثلةً سكندرية إذا كنا نخاطب أناسًا من الإسكندرية.

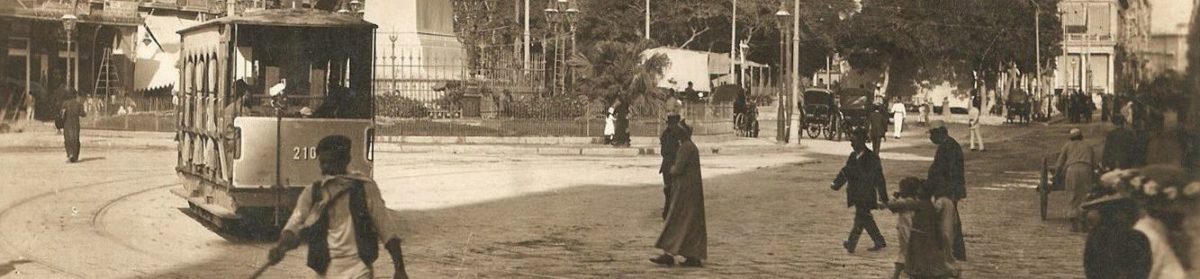

حنين إلى الإسكندرية

يؤكد “علي” أن الأسرة أدت دورًا كبيرًا في دفعه باتجاه الاهتمام بالعلوم في وقتٍ مبكر من حياته، مضيفًا: وُلدت في الإسكندرية، لكنني نشأت في أستراليا، لم يكن والدي معتادًا على القراءة، لكنه أراد تعويض ذلك من خلالي، كان والدي يشتري كتبًا باللغة الإنجليزية من أجل تشجيعي على القراءة، أحببت النظر إلى الخرائط، كنت أنظر إلى الخريطة وأبحث عن مصر وأتعجب من المسافة الكبيرة بين مصر وأستراليا، كنت أعيش في مدينة “بيرث” في غرب أستراليا، وهي مدينةٌ تُعرف بأنها “أبعد مدينة في العالم”، كنت أحلم بالعودة إلى مصر، من هنا بدأت أنظر إلى التعليم باعتباره وسيلةً للسفر ورؤية العالم.

يؤمن “علي” بأن الإسكندرية تمثل حلمًا وخيالًا لكل شخص بدايةً من مؤسسها الإسكندر الأكبر

ويضيف: لم أنسَ لحظةً أنني وُلدت في الإسكندرية، كنت أحرص على قراءة –ولو أشياء بسيطة- عنها، آمنت بأن الإسكندرية هي منبع الثقافة، يكفي أنها كانت مكانًا لمكتبة الإسكندرية القديمة التي احترقت في عام 48 قبل الميلاد، ميلادي في الإسكندرية خلق لديَّ شغفًا بالعلوم والتعليم، أؤمن بأن الإسكندرية تمثل حلمًا وخيالًا لكل شخص بدايةً من مؤسسها الإسكندر الأكبر ومرورًا بـ”ابن بطوطة” وغيره من الرحالة العرب الذين مروا عليها، هناك إحساس في مخيلة هؤلاء جميعًا بأن الإسكندرية تمثل المدينة الفاضلة، لا أحد يتحدث عن الإسكندرية بواقعية، ولكنهم يتحدثون دائمًا عنها بقدرٍ من الخيال.

جذبت “علي” أعمال “حنة أرندت” بعدما لفت انتباهه إليها المشرف على رسالته للدكتوراة، وتحديدًا كتابها “الحالة الإنسانية” (The Human Condition)، الذي أدى دورًا بارزًا في رحلة تطوره الفكري، مثلما أثرت فيه بشدة كتابات الدكتور إدوارد سعيد، أستاذ الأدب المقارن في جامعة كولومبيا الأمريكية.

الفلسفة والدين

يؤمن “علي” بأن الفلسفة ليست ضد الدين، مضيفًا في تصريحاته لـ”للعلم”: ترتبط الفلسفة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالدين والرياضيات والعلوم الطبيعية والتعليم والسياسة، وهي أم العلوم، ولا تعارُض بين أفكار الفيلسوف وتأملاته العقلية وعقيدته الدينية، لطالما سعيت إلى تبديد أسطورة أن الفلسفة تعارض الدين، وساعدني في ذلك الإشارة إلى أن شخصيات مسلمة مثل “الفارابي” و”ابن رشد” و”ابن سينا” كانوا فلاسفة، وحتى أبو حامد الغزالي، الذي يرى البعض أنه كان ضد الفلسفة، أتعامل معه باعتباره فيلسوفًا وأنه كان ضد جزء من الفلسفة كان موجودًا في عصره، وهناك أيضًا القديس أوغسطينوس، هناك -بطبيعة الحال- فلاسفة ملحدون، لكن هناك أيضًا فلاسفة متدينين على اختلاف دياناتهم السماوية.

الارتقاء بالعلوم الاجتماعية

يقول “علي”: نحتاج إلى الارتقاء بالعلوم الاجتماعية والإنسانية والفنون في المجتمعات العربية، لو كنت تجلس على مقهى في مصر وسألك أحد عن مهنتك، وقلت له إنك طبيب أو مهندس فسيتعامل معك باحترام، لكن لو أخبرته بأنك متخصص في الفلسفة أو علم الاجتماع أو التاريخ أو الفنون الجميلة، فسيتعامل معك باستغراب، وربما سألك عن سر اختيارك لتلك التخصصات التي لن تساعدك على تأسيس حياتك، تلك القاعدة تحتاج إلى تغيير، من الصعب أن تكون كلية الحقوق في أستراليا والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية كلية قمة بينما يحدث العكس تمامًا في مصر بالرغم من أن زعماء الحركة التاريخية المهتمين بمستقبل مصر -مثل مصطفى كامل ومحمد فريد وسعد زغلول- كانوا من خريجي الحقوق، أعرف أن الحقوق ليست من الآداب، لكن يجب تدريس العلوم الاجتماعية إجباريًّا في كل الجامعات كما هو الحال في العديد من الجامعات الغربية.

يوضح “علي” أن الفلسفة يمكنها تقديم صورة أكثر عمقًا ووضوحًا مما يبدو على السطح

ويضيف: تأثرت جدًّا بقصة قائد كشافة حضر إحدى ورش “مشروع التحرير لاونج– جوته”، التي كانت تُعقد تحت عنوان “مسرح الفكر”، قال هذا الكشاف إنه تمنَّى لو أحضر معه شابًّا في التاسعة عشرة من عمره لحضور هذه الفعاليات، وردت “منى شاهين” بأنه يمكنه إحضاره في الجلسة التالية، فأجاب قائد الكشافة بأن هذا لم يعد ممكنًا؛ لأنه كان يجلس مع هذا الشاب، الذي كان يستعد للالتحاق بكلية الهندسة، في مقهى بالقاهرة، وفي أثناء حديثهما، سمعهما النادل الذي يقدم القهوة وقال إنه خريج كلية الهندسة، أُصيب الشاب بالرعب من أن مستقبله قد ينتهي بتقديم القهوة بعد إنهاء دراسته الهندسية، وبعد يومين انتحر الشاب، يجب أن نتعلم أن كل مهنة لها كرامة.