My larticle on understanding the Egyptian political situation through the works of Hannah Arendt. Published in Politics in Spires

In Egypt, it is clear that constructive results are not going to materialise anytime soon. Increasing state violence, arrests and intimidation have no clear logic beyond an attempt by the security apparatus to regain power and tighten control over the economy. It is an outworn order that risks collapsing.

The insecurity of security

While the regime does have a serious security issue on its hands, namely the Sinai-based terrorism that has now spread to Cairo, the regime is increasingly blurring the lines between terrorism and anyone who opposes the official line. Labelling the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation, outlawing anti-regime protests, cracking down on NGOs and the clampdown against anti-regime activists and journalists are indications that the security state is disintegrating. The regime is carrying out violent measures against Islamists and youth – two major groups that cannot afford to be alienated – signalling the regime’s struggles to control a significant segment of the population via peaceful means.

According to Hesham Sellam, a fellow at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law, “These are the actions of a security apparatus that has lost the capability, coherence, and discipline to contain its challengers through targeted repression, and institutional and legal engineering.” Sallam argues that state increasingly can only justify its existence at the end of the barrel or through the desperate propagation of incoherent, xenophobic and militant nationalism. If this continues, he explains further, the Egyptian state will inevitably fail to establish any semblance of control, which successive governments have tried to impose since the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak.

In the meantime, there is no sign that the regime can deliver the security or stability that is required to attract tourists and investors. Billions in Gulf aid money will not resolve Egypt’s structural tensions. Reducing a bloated bureaucracy, addressing the subsidies burden and solving rampant unemployment remain in the queue. Meanwhile, with half of Egypt’s population under the age of 25, there is a startling lack of opportunity for an emerging generation.

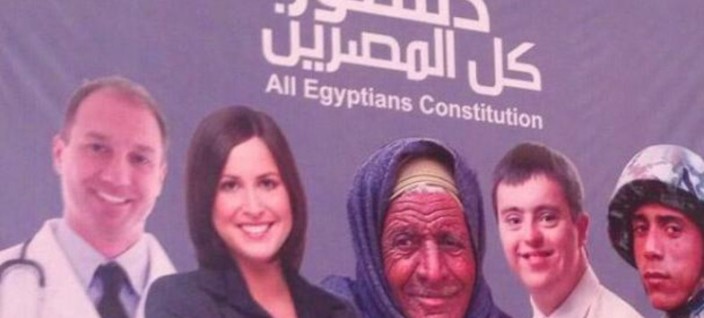

Egypt – politically, economically, and socially – cannot be saved through violent attack on dissenters, there is an urgent need for a broad political consensus to tackle longstanding crises.

Applying Arendt

Hannah Arendt’s understanding of violence can provide fundamental insights into the regime’s behaviour. In her 1972 work Crises of the Republic: Lying in Politics; Civil Disobedience; On Violence; Thoughts on Politics and Revolution, Arendt points out that the rise of state violence is frequently connected to a decrease in substantive power as regimes mistakenly believe they can retain real control through violent measures (CR 184). Real and sustainable power arises when a concert of people get together in a space to exchange views. Thus, power arises through free choice. Violence sits outside the realm of legitimate politics. It is an expression of desperation. It renders speech, discussions and persuasion impossible, making support from the public harder to come by.

Although she argues against violence, Arendt made qualified exceptions. She makes a point in her 1963 book On Revolution that violence may be required in initiating a new beginning such as a revolution in order to secure freedom. Yet this contrasts with the negative role of violence – its suppression of freedom. Contrary to the popular view of a peaceful uprising, the 2011 Egyptian revolution saw violent conduct from many protestors. Police stations were burned to the ground and symbols of the state were attacked. These actions, among many, helped to alter the political dynamics in favour of the street, and as Conor Cruise O’Brien once stated, “Violence is sometimes needed for the voice of moderation to be heard.”

Still, violence, state or otherwise, should not be glorified. State violence makes holding order difficult in the long term. As the bloody crackdown launched by the Egyptian security forces demonstrates, violence makes the situation unpredictable and perilous; it also does not guarantee the intended outcome. Arendt has much to say about this too. She remarks, “The danger of violence, even if it moves consciously within a non-extremist framework of short-term goals, will always be that the means overwhelm the end (OR 177).” The problem is that Egypt has long moved beyond such a framework. The spread of pain and suffering is too widespread to manage or control.

Arendt stresses that violence cannot create power, it can only destroy power (CR 155), meaning that it only takes away the conditions in which power can exist, merely forcing a group to disperse. Yet it does not create power which relies on the number of individuals supporting a certain group. In light of this, violence does not require numbers; it requires implements, the tools of violence that multiplies human strength. Therefore power is “not confronted by men but by men’s artefacts” (CR 106). As such, violence is the poorest foundation for a new government.

Arendt uses the example of a disruption in a university class. If one student successfully disrupts the class by yelling or using violence, while all other students choose to carry on peacefully, this breakdown in the academic process would not be due to the disruptive student’s greater power, but rather due to the entire group of students’ choice not to exercise its power to overpower the student (CR 141). In the context of the Egyptian regime, security sector violence subdues the majority to cause it not to exercise its power.

A search for salvation

To survive, a regime needs a genuine powerbase of believers (CR 149). This powerbase, at the moment, appears to be a large swathe of the Egyptian public cheering on the crackdowns and arrests, and adulating Field Marshal Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi as their messiah. Sisi does not want to become a dictator as much as the people want to make him one. Yet this base rests largely on a quickly hatched informal pact in which the instability-weary public surrenders democratic governance in exchange for security and economic progress. Neither is likely to eventuate, further entrenching the use of violence and consequently exacerbating the instability of the regime.

Arendt warns that violence, like any mode of action, can change the world, but alas, the most probable change is to a more violent world (OR 177). Yet as she notes in The Human Condition(1958), the unpredictability of political action and violence can be countered through promises and forgiveness to help stabilise action and provide healing. Making and keeping promises helps to give signals to the public about the future, ensuring steadfastness. Forgiveness tempers the irreversibility of violence by forgiving past mistakes (HC 241). An alternative to forgiveness is punishment, which involves reparations to rectify the original transgression and bring it to a close. This should not be confused with vengeance that reacts by perpetrating a mirror image of the original wrong.

Distressingly, the Egyptian story of the past three years has been anything but promise, forgiveness and punishment. Instead, it has been one of promises to elites, forgiveness for old regime figures, and punishment for those who criticise the established state chorus.

As elites seek to exhaust every polarising measure before arriving at the obvious station of compromise, Egypt’s road to progressive and inclusive politics is going to be stained red with calamity. In the absence of a visionary leadership, violence will likely continue unabated and further enflame the serious empathy drought in the public discourse.

The spectre of unpredictability, an important Arendtian theme, is another added challenge for the state. The 2011 Revolution brought a new beginning which opened up spaces in which individuals could share with one another their identity and engage in speech and action in which freedom and plurality materialised. It was a Pandora’s Box that unleashed a wave of political change that cannot tolerate the resurrection of Mubarak-style authoritarianism for the very reason that its foundational social contract is no longer feasible. In a paradoxical way, Egypt is a new Egypt even if it still looks like old Egypt.

It may be the case that Egypt’s move towards democracy will eventually happen because they will be left with no other choice as the tools of violence become blunted, but this will not be because the establishment will simply have a change of heart.

“To substitute violence for power can bring victory,” Arendt states, “but the price is very high; for it is not only paid by the vanquished but it is also paid by the victor” (CR 152).

The question now remains how high a price is Egypt’s regime willing to pay, and also how long the classroom will remain apathetic. A state is predictable, a revolution is not.