Published in the Atlantic Council

By the time philosopher Hannah Arendt penned the words in her 1970 work On Violence: “The means used to achieve political goals are more often than not of greater relevance to the future world than the intended goals,” a generation of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood transitioning into the Anwar Sadat era were reeling from the “means” of imprisonment and torture. For sixteen years, under the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the ideological foundations of radical Islamism were largely nurtured in Egypt’s prison system, and exported to the rest of the world. It became painfully clear with time, the Brotherhood and Islamists had to be co-opted into the political process, rather than rewind the clock back to 1954.

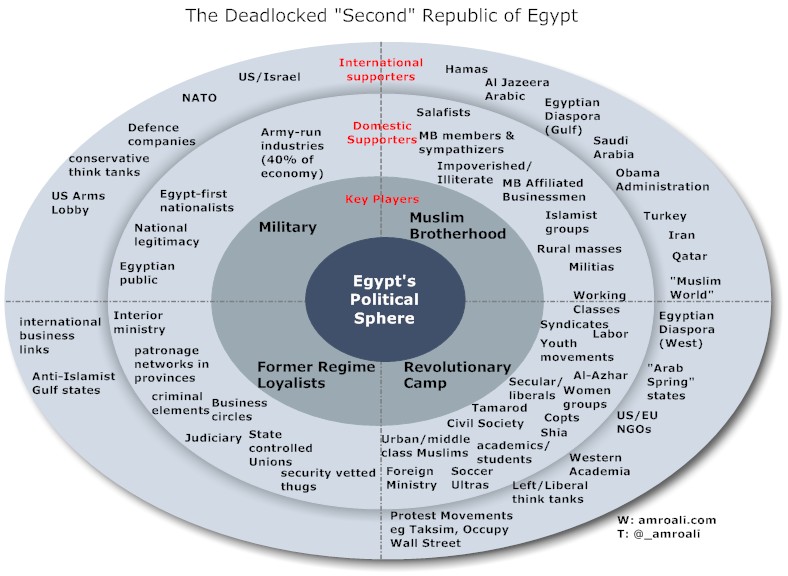

Over the past three months, security services have arrested key Brotherhood figures, in effect decapitating the organization’s first and second tier leadership, shutting down media outlets, seizing its assets, demonizing the group, arresting and killing countless supporters. Now the latest court ruling to ban the eighty-five year old organization is on the table. It is becoming obvious that Egypt’s political and security elites envision an Egyptian future in which the Brotherhood and its support networks are completely destroyed or incapacitated. Such a short-sighted move overlooks the group’s proven survival mechanisms.

In the tightly-controlled public sphere and information space of Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s, Brotherhood inmates, intentionally dispersed across the country’s prisons in order to cripple the apparatus, were largely survived by the (little-known) Muslim Sisterhood. The latter acted as an informal prison support network, carrying ideas and messages from prison to prison to sustain the Brotherhood, and were vital to their rebirth.

Today, there is no need for prison support networks when that network now has a stronger international reach. No longer limited to the Gulf and London, the Brotherhood is opening offices as far flung as Australia. These groups are geared towards revising the Brotherhood strategy and wait for another political opening in Egypt. They are also making efforts to disturb diplomatic relations, skewing the Muslim world view of Egypt, splintering an already splintered diaspora, and pushing a clear-cut anti-coup narrative as opposed to the pro-army’s ill-defined ‘war on terrorism’ battle cry that has come to encompass Sinai’s violent extremism and Pro-Brotherhood protestors throughout Egypt

Recent events have enabled the Brotherhood to take the high moral ground, when addressing both their domestic constituencies and foreign audiences, depicting an Egypt engaged in a secular or religious sacred drama, nicely divided into digestible binaries. To the West, the Brotherhood argues that they are the torchbearers of democracy that are fighting the return of an authoritarian state that overthrew Morsi. To the Muslim world, the Brotherhood has effectively portrayed itself as the defender of Islam, battling godless secularism in the heart of the Sunni intellectual nerve centre.

It does not seem to matter that Morsi and the Brotherhood took a destructive course while in power, that a majority of Egyptians, including Al-Azhar and religious Muslims, have a highly unfavourable view of the Brotherhood or that the organization’s polarizing discourse of incitement and victimhood provides the cover for the killing and destruction of property. A sophisticated and nuanced reading into why Morsi and the Brotherhood collapsed and are largely unpopular is lost in translation.

And why should it not be? The rise in strains of liberal tyranny to rival the strains in religious tyranny gutted the moral clout of anti-Brotherhood arguments, let alone the argument to shut them down. Egypt has been transformed into a bear pit that is locked in an existential battle for survival, with each side going as far as targeting the perceived allied minorities of the other camp: non-Islamists target Syrian and Palestinian refugees, and more violently, the Islamists target Christians and their churches.

Given that the power cards are heavily stacked in favor of the military and security forces, and by extension, the interim government; they need to seriously address the imagination crisis that deal with security issues. It should be noted, no matter how ‘well-intentioned,’ the sight of a military machine carrying out killings in Cairo’s squares for the benefit of ‘your side’ does not score points with the rest of the world. More so when state media is fanning the flames of xenophobia and the arrest of foreign nationals occur in a country in dire need of tourists.

Yet no questions are being asked, how the child who lost his pro-Brotherhood parents in the Raba’a massacre will grow up in a society that largely cheered on the violent dispersals. Or how Islamists will ever trust the democratic process when they are continually being marginalized. Or the Coptic child who lost a father because the security forces did not turn up – some would argue strategically delayed to tarnish the Brotherhood – to protect Christian communities and churches when the threat of an Islamist mob was imminent in the usual rural flashpoints. These are the seeds of bitterness that will matter more to the future Egypt than the current intended myopic goals.

There is little doubt that laws need to be passed to prevent the misuse of mosques for political campaigning and sectarian incitement. The Brotherhood needs to be legally obliged to become transparent with its activities, and importantly, pushed into a state of self-reflection. Banning the organization pushes its members further back into their traditional comfort zone in which they thrive – victimhood and opposition.

As highly problematic as the organization is, the Brotherhood is not the by-product of a foreign plot, rather it is a by-product of Egypt’s social forces and needs to be reintegrated into a system of transitional justice and national reconciliation. Targeting the Brotherhood’s social support networks – healthcare, education, and welfare services – will have a crippling effect on the rural poor. The state is too incompetent to fill the void. Former regime loyalists and revolutionary forces struggle to run an effective political campaign in these areas, let alone service their basic needs.

The late poet Mahmoud Darwish sounded a warning: “Those who spend an era breastfeeding from the milk of cruel despotism can only perceive destruction and evil in freedom.” In this lays the grim inheritance bestowed upon Egypt following decades of authoritarian rule, the public not only perceives destruction and evil in its own freedom, but in the freedom of others and, consequently, any notion of political co-existence. A third route is needed to save it. Instead of crushing the Brotherhood, there needs to be a national inclusive dialogue on the role of religion and politics, a focus on strengthening institutional checks and balances, and the enforcement of rule of law to protect Egypt from political and security violations and excesses, whether by Islamists or otherwise.

Egypt deserves better.