When Henry Kissinger once queried the Chinese Premier Zhou En Lai in 1971 for his views on the consequences of the French Revolution, Zhou famously respond, “It is too early to tell”. In other words, 180 years notwithstanding, Zhou’s point was that the consequences of social revolutions do not crystallise until much later.

Academics who specialise in revolutions and Middle East studies are often fond of quoting the Zhou lesson yet are quick to omit social media from the discourse explaining the recent revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt. Since January, I have attended countless academic seminars discussing the uprisings where specialists are downplaying social media to such an extent as to make it inconsequential. You know you are in for the long haul when a speaker remarks smugly that Facebook did as much for Egypt as the fax machine did for the fall of the Berlin wall.

The line goes something like this: “The revolutions of the French, the Russians, the Iranians, are proof that you do not need social media”. This argument has been repeated to me ad nauseum. Moreover, the critics are engaged in the logical fallacy they often warn against: argumentum ad antiquitatem, “appeal to tradition”, that is to say, because it happened in this manner in the past, it has to be correct. Continue reading “The War of Academia on Social Media”

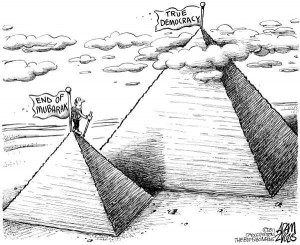

It was Lenin who once said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”. After decades of stagnation under Mubarak, there could not have been a more fitting description for the events in Egypt of early 2011.

It was Lenin who once said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”. After decades of stagnation under Mubarak, there could not have been a more fitting description for the events in Egypt of early 2011. In a bustling area of the 2,300 year-old Alexandria, Egypt, lies the middle class suburb of Cleopatra

In a bustling area of the 2,300 year-old Alexandria, Egypt, lies the middle class suburb of Cleopatra