Published in GQ Magazine

In 1993, Ahmed Khaled Tawfik began a series of sci-fi horror books that would change the lives of millions in the Middle East. Now translated into a new Netflix series, Paranormal is set to bring Egyptian storytelling to the world

Ahmed Khaled Tawfik knew that it would happen after his death. The big fame, that is, the fame that translated from 15 million copies shifted of 81 best-selling novels in a genre that was quite frankly non-existent in the Middle East up until he and his work arrived. Now, as Netflix prepares to drop Paranormal (you’ll likely know it better as Ma Waraa al-Tabeea), a series based on his revolutionary sci-fi horror novels, you get the impression that he might just have been right.

It may seem ironic that a region with more than its fair share of real-world horror is so lacking in the storytelling genre, but that’s not because the stories would be hard-pressed to keep up with the news. Chalk it up instead to misunderstanding. Analysts would often ask the late Egyptian novelist why Arab youth resorted to reading his gothic horror stories if their own lives were already steeped in pain, anxiety and uncertainty? Exactly what type of escapism could books like these possibly provide? Tawfik knew only too well.

“The idea of reading horror is that you approach death without dying.”

“Horror provides a nominal escape from your problems because, no matter how bad your life is, the horror story can show us that it could be much worse,” he once said. “The idea of reading horror is that you approach death without dying.”

Tawfik’s enormous readership and success with the pocket novel series featuring the cynical, dark-humoured Dr Refaat Ismail was proof positive that it was exactly what the region was looking for. And the character’s resurrection via Netflix is set to be nothing short of groundbreaking – in more ways than one.

The production has attracted award-winning heavyweights. Paranormal is directed and produced by Amr Salama (Sheikh Jackson, Excuse My French, Asmaa), and co-produced by Mohamed Hefzy (Clash, Yomeddine, You Will Die at Twenty). It’s the third Arabic and the first Egyptian Netflix Original production and, as Ahmed Amin, who plays Dr Ismail, rightly exclaims, “The series will hopefully open a window to the world and exclaim that there is an original and influential horror genre happening in Egypt.”

For those who have never touched the books: Ismail is an aging haematologist who encounters a world where logic and scientific reason are replaced with local mythology and global folk tales. Ismail takes on a “journey of doubt” – battling numerous health problems with a ready supply of medicines rattling in his pockets as he goes. He is an anti-hero so ordinary and frail that he came to be loved. Unlike previous heroes in Arabic literature, Ismail mirrored the torrent of failings and contradictions in Arab societies. Regional publication ArabLit painted him as a breakaway from “the squeaky clean image of the hero in Arabic writing”. Arabic folklore has usually favoured “knights on horseback” and moral absolutisms. Ismail was plain, yet imaginative enough to draw the reader into his animated world. This meant something to the young people in Mubarak’s Egypt, where you could argue imagination was overshadowed by a prevailing zeitgeist of mediocrity.

The show’s director and executive producer, Amr Salama, has waited years to realise his vision

It pays to be clear. Perhaps no Arab author has been as underrated as Tawfik. Born in the Egyptian city of Tanta in 1962, he became a physician and professor of tropical medicines at Tanta University, eventually diverting a slice of his attention to fiction writing. “My English was not yet good enough to read horror literature, so I started writing it myself,” he once said. Cut-off from the literary influences of the English-dominated fiction book market – and with Arabic horror novels non-existent – he began to construct his own world based around the turbulent experiences of Egyptian life. “If I had read Howard Phillips Lovecraft, Stephen King, [and Mary Shelley], I would never have written,” he said. “I would have just been satisfied with what I was reading.” But there was influence there. Only rather than Anglo-fiction, it ended up being the works of Anton Chekhov, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy that would silently mentor him.

If you would really like to see a measure of what young people in Egypt thought of Tawfik, you need only to look at his death in 2018. Attracting thousands of young mourners to his funeral, the footage sent shockwaves through the Cairo establishment, bewildered at how a dead novelist who they had barely registered as a legitimate cultural influence could so effortlessly draw more Egyptian youth than an election.

In the early 1990s, a young Amr Salama went hunting for a book that came from Egypt – any book – at the one store he frequented while growing up in Saudi Arabia. He stumbled upon a section titled “Egyptian Pocketbook Novels” and it filled him with excitement, addressing the void in a boy longing for his home in Cairo. His purchase was from the Paranormal series – the first books he would ever read outside of his school curriculum – and they would stay with him for life. Years later in 2006, while still a budding director, Salama contacted Tawfik with an idea to turn Paranormal into a TV series. They struck a warm, long friendship. “He was like a father to me,” Salama would later say.

Bit by bit, the pair made plans both precise and ambitious, building a vision that would not be compromised. One of the agreements: they would not straitjacket the novels to fit the 30-day Ramadan series schedule – a time when television in the Arab world is sacred. “Not doing the 30 Ramadan episodes allowed for a certain slowness and quality,” says Majid Al Ansari, the second block director for the series. And that liberation is quite telling. The first scripts appeared in 2006 and have been reviewed word-by-word on a regular basis ever since. Filming was undertaken in sections to foster synchroneity and flow, and authenticity was demanded in everything. Salama did not want to rely on tropes imported from abroad. “We want to give an Egyptian voice and sound it to the world,” he says.

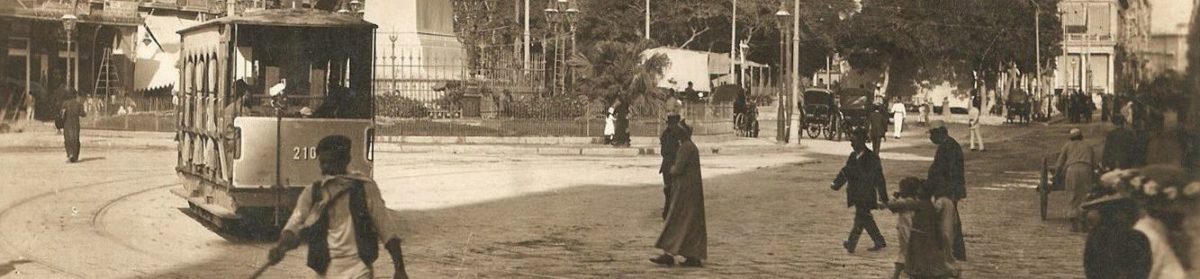

Nothing was spared when it came to remaining true to the story. Even though the Abu Rehab palace, located in Cairo’s El Manial district, was constructed in the 1940s, production designer Ali Hossam felt that they needed to bring it in tune with the villa in the novels that was built in 1880. And that included efforts to give it a rural grassy surrounding to mimic the belle époque villas and mansions that once stood in Nile Delta cities like Mansoura in the colonial era.

Walking through the house early in the production, it’s clear that the set designs were thoroughly considered to meet the exacting standards of not only Netflix, but Salama – and indeed, the late Tawfik – too. After all, this is meant to be a haunted house, so there’s an abundance of dust, chandeliers with broken strings of crystals, peeling wallpaper, torn curtains, old portraits, gloomy staircases, and a wealth of cobwebs all over. It dawns on me that most Egyptian homes, if left unattended for a few years, actually look somewhat like this. Elsewhere, the special effects and makeup team, Donia Sedky and Eslam Alex, explain the steps of transforming a child actor into a hideous demonic character (apparently the children have more patience and stamina for this laborious process than adults).

Amin says that he is confident that audiences will come to see a series that was made with “sincerity, detailed attention, and responsibility” – and that Tawfik’s world of Cairo in 1969 is captured in piercing detail. It reflects the mood of a public that had long outgrown political rallies and anti-colonial exhilaration and now walked despondently in the shadow of Nasser’s Egypt. Reeling from defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War, there was an ambivalence with the quasi-socialist experiment and a shattering of pan-Arabist dreams, only to perhaps find comfort in the inordinate amount of trees lining the streets. This is a long-forgotten version of Egypt that operated in a poetically slow mode: from the Cadillacs to the iconic black and white Fiat taxis roaming in second or third gear. High pressure capitalism was yet to make its mark in Cairo and life was set at a much more gradual pace.

Lebanese-British actress Razane Jammal – whose previous projects are as varied as Djinn and Kanye West’s Cruel Summer – plays scientist Maggie McKillop

Salama admits that capturing the true essence of the book’s various time periods was a sizeable challenge. “The more you went back in time, the more difficult it was to portray the details.” While 1969 might have been relatively easy to establish costume, casting, and setting, 1941 was much more difficult, and 1910 even more so.

There was also initial controversy surrounding the casting of Amin in the starring role as Ismail, largely due to the actor’s longstanding association with comedy. Just how could the man that made his name in 30-second viral videos on Facebook play the austere and introspective Ismail? Thankfully, it turns out that Amin had long been a fan of the series, and is well-read on Tawfik’s other works too. As a result, he was able to create a multi-dimensional, compelling character that even the most ardent of Tawfik’s fans will likely appreciate. And while Salama naturally took some creative licence in adapting Paranormal to the screen, it was done with Tawfik’s blessing and is largely faithful to the spirit of the novel.

The series raises broader questions, too, about just how this project can resonate in the current climate of entertainment saturation. While lockdown has amplified our reliance on streaming services, it’s a trend that has been gaining momentum for years. Popular culture that was once drip fed to us over weeks is now drilled straight into our veins. “Before the pandemic I would watch a season per month,” admits Salama. “Now I watch a season per day, and if you asked me what I watched yesterday I wouldn’t even remember. The side effect now could be that one show gets talked about for two days instead of a month.”

“If we achieve this, it will be a breakthrough for Egypt and the Arab world. It will raise the standard of what we can provide for the world.”

Amin’s casting has raised eyebrows, but he’s long been a fan of the series

Amin’s casting has raised eyebrows, but he’s long been a fan of the series

But Paranormal is highly unlikely to suffer a fate of irrelevance, given it can count on a large fan base that has steadily grown since the early ’90s. It has influenced multiple generations of readers, producing a readymade demographic built on a love of literary quality and the essence of a sublime, horrifying story. The team stress that this is what they are taking to the Netflix table. “Human values are quite consistent when it comes to the idea of a good story,” says Amin. “People love a good storyteller, and in a beautiful tale there are meanings connected to the human being in every place – irrespective of geography and language.” As a result, they hope the project will be a watershed moment for the region, offering mass exposure to Middle Eastern storytelling in much the same way that Money Heist shone a light on talent from Spain. “If we achieve this, it will be a breakthrough for Egypt and the Arab world,” says Salama. “It will raise the standard of what we can provide for the world.” Aya Samaha, who plays Ismail’s embittered fiancée Huwaida, argues that the screen version has a longevity and even stronger effect than the book, enabling it to provide a holistic picture. “We are in a win-win situation, as the novels are already a success, and the fans are everywhere. But now they will see it as a clearer picture. If we give it depth and detail it will complement the longevity of the novels themselves.”

On a TV programme in 2014, viewers were invited to call in and ask questions of that episode’s guest, Ahmed Khaled Tawfik. One of the callers was Salama, who delivered a touching message to his friend. “I want you to know that as long as I live, I promise I will fight until Paranormal comes to light in the best shape and best quality to be competitive on the global stage,” he said. Later conversations between the pair would see Tawfik explain his regret that he may never see the day Salama’s promise came true.

But success for Paranormal is about more than mere posthumous fame. While only one of Tawfik’s books has so far been translated into another language (Utopia, 2008), Salama believes that this great eulogy via Netflix could be the moment that changes everything. The moment that Middle Eastern stories are told to the world, and the moment that Dr Refaat Ismail once more comes to life. Tawfik, you know, would have heartily approved.

Paranormal releases on Netflix on November 5.