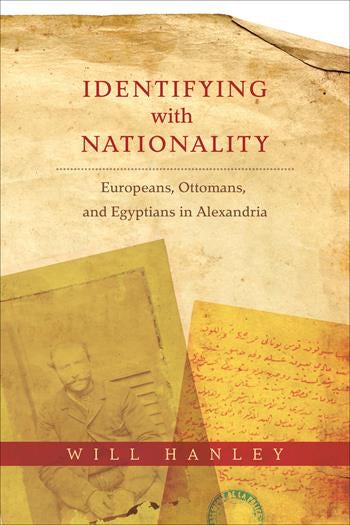

My book review of Will Hanley’s work “Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria” has been published in the Mashriq & Mahjar journal (Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies, North Carolina State University). The PDF article is open access.

REVIEWED BY AMRO ALI, American University in Cairo

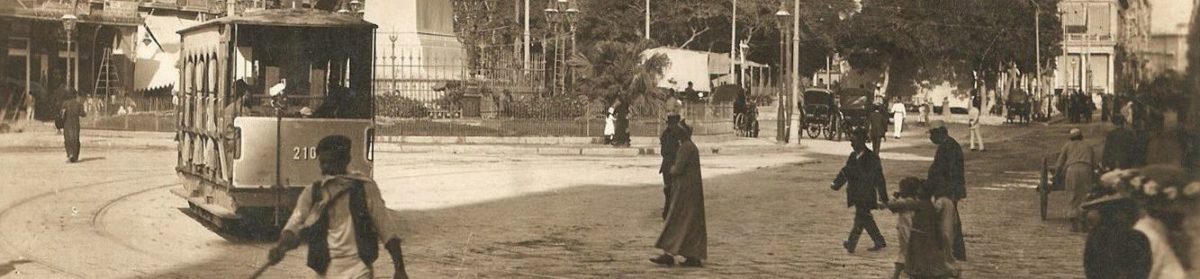

“Who are you?” is an all too familiar question in everyday life, one that is neither bound by time nor place, but can carry extraordinary consequences for the person being asked, and for history itself. It is a question that is central to Will Hanley’s outstanding book, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria, which illuminates Alexandria as a key sociolegal laboratory in the making of our modern world, covering the decades between the early 1880s and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. In this short pivotal span of history, Hanley telescopes into an enriching fusion of people from different countries who crossed each other’s paths on the streets, sidewalks, trams, trains, cafés, restaurants, and theatres. For many, the idea of personal identity revolved around timeless identifiers such as birthplace, religion, and marital status. They also had a nationality label but this, particularly until the 1880s, was usually a dormant, if not meaningless, category. That is, nationality suddenly meant everything when it became both a formal and informal requirement by the authorities or offered social and legal advantages.[1] That realization would bring people, and hence cement their cases on paper, to the police stations, consulates, and courts of Alexandria. The “wrong” nationality, like a Cypriot, could be a burden on the individual, while a privileged nationality, such as French or British, could mean protection from prison and access to wealth.[2] Egyptians, for whom the idea of nationality was yet to gain any social and legal coherence, were disgruntled at the nationality scourge that not only disadvantaged them compared to other nationalities, but the questionable court sentences and dubious acquittals also served to prove that the “outward garment of nationality concealed the domestication of the rule of difference.”[3]

Hanley’s book is divided into three parts, containing twelve chapters, an introduction, and an epilogue. In section one, “Settings,” Hanley illustrates the organizing concept of “vulgar cosmopolitanism” in chapter one. This concept drives the book’s key theme that shifts our familiar notion of Alexandria from a romanticized understanding and elite-centered cosmopolitanism to the mundane everyday life of Alexandria. The latter is where the matrix of passing, ignoring, jostling, and arguing occurs with habitual frequency until it crosses into legal territory, such as breaking the law, often lubricated by liquor and fomented by misunderstanding. Chapter two fleshes out keywords: national, citizen, resident, foreigner, and subject. The chapter aims to map out the book’s conceptual topology and the placement of individuals and their identities in the making of the emerging world at the turn of the twentieth-century.

In the second section, “Means,” Hanley scrutinizes the mediums of identification in the daily lives of society through the chapters of —“Papers,” “Census,” “Money,” and “Marriage” — which taught the population to identify with new labeling practices and familiarize themselves with a new vocabulary. The chapter “Papers” explores how passports and identification documents became the portable and impersonal means for the authorities to manage the mobility of individuals. While the chapter “Census” looks at the product of the state’s appetite to amplify its state-building project, negotiate disputes with diplomatic authorities over nationalities, and centralize the certification of identity. [4] The chapter on money fleshes out how currency became symbols for the emerging political and economic order and, hence, it required that tokens be honored. In light of this, counterfeiting was seen as an egregious crime, as it challenged the official order and the state’s power to circulate and monopolize symbols of value. The standardization of currency and material advantages sharpened the ability for nationalities to gain access to benefits and favorable rulings from judicial institutions that were predisposed towards wealthy national communities. [5] Finally, the last chapter of the section, “Marriage,” was a site of administrative anxiety given that nationality was largely a gendered practice by how easy it was for women to switch to their husband’s nationality or retain their father’s nationality through marriage, remarriage, separation, or divorce. But their transition depended upon the usefulness of the nationality in question, thus making marriage the “driving wheel of nationality litigation and legislation.” [6]

Hanley’s third section, “Other Nationalities,” spans six chapters: “Europeans,” “Foreigners,” “Protégés,” “Bad subjects,” “Ottomans,” and “Locals,” which takes up the larger essence of the book, as it seeks to map out the triumph of the nationality category, even with its precarities, over other markers of identification. Yet, Hanley takes us into a more complicated field beyond “powerful” Europeans and “weak” natives, as colonial privilege could not be easily deployed as distinctions were rarely obvious. For example, outside the small circles of European notables whom clearly had brazen privilege, poorer Europeans found themselves constrained by class, race, or gender.[7] Similarly, non-European foreigners like Tunisians and Maltese, who were imperial subjects, could exercise benefits in Egypt that were not possible back in their home country.

The case against Alexandrian cosmopolitanism that privileges elites and pioneers is certainly not new and has been fashionable in academic circles for many years. The author, however, gives the subject matter justice as he makes a strong case for shifting from the elites and small literary circles that intended to leave a legacy of written accounts, to the ordinary Alexandrians who did not. Thus, the book’s outcome is a one-by-one pointillist tapestry that draws you into a different Alexandria. Hanley argues against the proponents of triumphalist histories, writing, “We are not obliged to grant the nation the epic imaginary proportions,” and in making the case for the everyday ordinary, ironically, gives his work a distinguished epic of its own.[8] All accounts ended up in court and consulate documents, much like the recorded banal exchange between two Maltese friends, reading, “Today is Saturday, let us go and have a walk,” and ends with one friend fatally stabbing the other. [9] The dizzying number of accounts reads like miniature dramas with an endless cast of actors straddling the turn of the century, dazzling the city, and animating the era in fascinating ways. Taking the stage is the Cypriot realizing his Ottoman-ruled origins offered no protection from torture in a police station; the Egyptian woman who fell in love with an Italian man causing a scandal; the British consular official rushing to stop a marriage between a British Christian woman and an Egyptian Muslim man; an Irishman pretending to be an irrigation inspector to get a tasty meal and “borrow” ten francs from a priest; a French winemaker surprised that he would be imprisoned after he overestimated his foreign privilege by beating up an Egyptian tram conductor; And, eyewitness testimonies by Austrian barmaids pronouncing Islamic oaths. What Hanley’s book does is it upends what may have been thought to be established and predictable about nationality.

The label of nationality—the ever-recurring term that leads you through the book’s thematic kaleidoscope—creeps its way into the realm of individual identity, which was traditionally reserved for one’s name, occupation, place of origin, sect, and physical description. These attributes had to compete with “colonialism’s will to categorize populations and its pervasive expressions of power through small mechanisms and technologies and its modernity,” all of which were recognizable through nationality (though not the same as citizenship, which is a concept that would later become a key aim in decolonization movements).[10] This can be seen in Alexandria’s Maghribis up until the early 1880s, who were considered by local Egyptians as different, but not foreign. This invention of a nationality category, however, not only now made them foreign, but their status from a French colony also gave them further layers of protection (still short of the full legal protections that French nationals received) that unnerved locals, especially when nationality departed from the ordinary practice of the social into an exercise of its legality.

Identifying with Nationality is part of a trend that slowly crystallized in the mid-2000s and accelerated following the 2011 Egyptian revolution, which saw scholarship on Alexandria breaking the historical imperial-nationalist dichotomy that left little room for nuances. This shift took place amid a form of culture war between generations of Alexandrians, political positioning, and struggles to reconcile with the contradicting elements of the past. Perhaps beyond the book’s scope, it would have been worthwhile to give a brief analysis on modern Alexandria in the epilogue given the city was the ground zero and laboratory for the invented nationality category. Particularly because Hanley notes: “Alexandria was thus a bellwether for nationality changes that would spread worldwide in the twentieth century.” [11] As a resident of Alexandria myself, I wonder if modern Alexandria is a bellwether or troubling parable for the dysfunctions of nationality, as one sees the book’s longue durée projected into the present day as residents dwell on the debris left by nationality, nationalism, and an enduring colonial logic, which still scars Alexandria.

Hanley offers readers poignant lessons for our times, particularly given the triumph of nationality after World War I, which canonized smaller subsets of nationalities that we grapple with today, such as the “stateless, refugee, colonial subject, foreigner, and minority.”[12] Egypt’s Muslim-Christian relations, for example, were not without strain before the nationality category, but they were at least resolvable at the local level because differences were clearly known, understood, and mediated through a familiar pattern to the respective population center. Nationality, ironically, exacerbated religious tensions as it papered over differences and paved the way for state intrusion into local community matters. Even “Egyptian” did not hold much meaning for many Egyptians prior to the 1880s. The category only became important for bureaucratic reasons, not for membership of the watan (nation) or for paying homage to some pharaonic ancestry.[13] Rather, it was Egyptian elites who adopted the mantle of nationalism in order to wield “the resources of the state in their own interest” and saw to it that “nationalism expanded along the stolid avenue of self-interest.”[14] For the rest of the non-elite Egyptians, it would take decades to adopt the nationality label in any legal and nationalist sense. This reluctance can be explained, as Hanley puts it, because “the benefits of local status were often more obscure than its costs,” especially in terms of the burden of taxes and ruthless conscription, from which foreign nationals were free from.[15]

In traversing over four thousand cases, with over ten thousand individuals, and drawn from archives in five different languages from six different countries, Hanley delivers a superb piece of work in historical research, rethinking social history, and reevaluating national taxonomies, rather than assuming them. This book makes a significant and original contribution to the fields of transnationalism, citizenship, cosmopolitanism, comparative colonial studies, international law, Egyptian history, Alexandria’s urban history, and Mediterranean migration. It would appeal to both graduate students and scholars, but also to the informed public interested in these topics, as Identifying with Nationality, to its credit, does not intimidate the reader unfamiliar with legal jargon. The author has been merciful in making legal terms clearly legible, as well as subsuming them into captivating miniature narratives and vignettes that animate the sociolegal story of a bygone Alexandria. Therefore, it is not only a book that comprehensively adds to scholarship, but is ripe with countless gems to inspire future plays, poems, and stories.

NOTES

[1] Will Hanley, Identifying with Nationality: Europeans, Ottomans, and Egyptians in Alexandria (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 287.

[4] Ibid., 119.

[5] Ibid., 136.

[6] Ibid., 138.

[7] Ibid., 157.

[8] Ibid., 3.

[9] Ibid., 43.

[10] Ibid., 7.

[11] Ibid., 21.

[12] Ibid., 281.

[13] Ibid., 296.

[14] Ibid., 288.

[15] Ibid., 289.