Published in Mada Masr

Published in Mada Masr

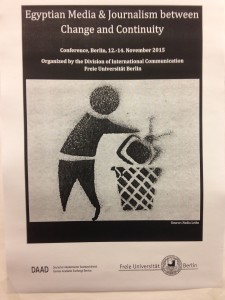

“In Egypt, there is freedom of speech, but no freedom after speech” – went the running joke at a recent conference in Berlin that brought a number of prominent Egyptian media figures and scholars together. The aim was to discuss the deplorable state of the country’s lack of freedom of the press, amid a wide-scale assault on professional journalism. With minimal risk of security forces storming the event Cairo-style (or cancelling it), the space was wide open for a conversation on how journalists deal with the challenges of operating in a state of repression, and for crafting a way forward.

The event took place as journalists are being arrested and harassed in Egypt – a country which ranks 158 out in 180 countries in the 2015 World Press Freedom Index. Ismail Alexandrani is among the latest journalists to be detained (as a result of a tip-off from the Egyptian embassy in Berlin).

Figures and reports cannot, however, capture the human anxiety, courage and endurance that characterises the lives of Egyptian journalists when they decide to step out of line with the regime.

In her opening speech, Reem Maguid, a popular media anchor hounded by the regime, harkened back to an old Egyptian proverb, “Is there shame in [asking] a question?” This basic journalistic exercise of asking a question, Maguid added, often outrages authorities, which makes it clear that it is not the question that is the problem, but the mere act of asking and thinking.

The answer to Maguid’s question could perhaps be partly found in the ordeal of Hossam Bahgat’s incarceration. Bahgat, a journalist with Mada Masr, was taken into military detention for writing an article on the military. Bahgat was asked one question through the hours in detention by everyone, even those who were not involved in his prosecution case: “Why did you write about the military?” Incessantly repeated, it eventually dawned on Bahgat that the question was in fact genuine. The conflict between Egypt’s professional journalists and the regime, Bahgat noted, does not happen at the level of discourse or policies, but is more fundamental; it is a question of opposing worldviews; “Anything that deviates from the official line is seen as a weird phenomenon,” he explained.

Many independent-minded journalists are determined to hold onto the relative media freedoms they enjoyed in 2011–2012 following the uprising that toppled former President Hosni Mubarak. Nevertheless, researcher Mostafa Shaat points out how freedoms in that period were simply “political bargains forced on the political regime by the waves of mass protests.” Now the state, Shaat emphasizes, has returned to rewarding its loyal journalists with legal immunity from prosecution, while deliberately targeting independent journalists.

There is an overall feeling of arbitrariness in how decisions are made in today’s peculiar form of despotism. Different security agencies were apparently unaware that Bahgat had been summoned. This state of arbitrariness and unpredictability makes the situation even more frightening. “Never underestimate the stupidity of dictators,” Bahgat added. “These are not rational people; you should not look for a reason.”

Hitting a similar note, maverick media anchor Yosri Fouda pleaded for common sense to come back into high politics. “It’s important we move in the right direction. Don’t tell me the train is going to Aswan when it’s heading to Alexandria!” Fouda exclaimed.

The question of courage was naturally a topic journalists often grappled with. Maguid gave a moving account: “Being brave is great, but being professional is greater [long silence]. But we are weak. The price paid is getting higher. At some point, I was ready to be jailed or killed. But I’m not ready for harm to come to my family. I’m not ready for them to pay the price for me.”

For those walking the line of investigative journalism, Bahgat gave this warning: “There is a difference between being a brave journalist and a reckless one. Martyrdom does not feel good when you are locked up. Don’t try to be a martyr without at least calculating the consequences.”

Yet what drives journalism is a quest for the truth. “I am incapable of telling half the truth,” said Maguid. Bahgat noted that there is a “crisis when security forces kill people in an apartment and say it was an exchange of fire – that there can be no other narrative to this.”

Regarding his controversial article, Bahgat addressed the need to break boundaries and set precedents. “I feel insulted at the silent imaginary gag order in which journalists are not allowed to report that a trial even happened. What is worse and more dangerous than censorship, physical danger, or losing your job – is failing to report the story. I wanted to show you can run the story, that it can be done.”

But he warns that “it took many weeks before I decided the story was ready. Have all the evidence, introduce editorial concessions, make the story possible to defend… minimise the damage that can be done.”

However, he conceded that Mada Masr had underestimated the military’s attention to online media. “What’s depressing is that even when you follow journalistic ethics, you are [still] not safe,” he said.

These word echoed those of Abeer Saady, from Egypt’s journalism syndicate, who underscored self-responsibility among journalists: “If you don’t regulate yourself as a journalist. Then someone else will.”

Fouda reminded the audience what their profession is supposed to entail: “Our job as journalists is not to facilitate an easy life for the authorities.”

While the question of how to advance Egypt’s journalism saw a difference of opinions, what was certainly easier to acknowledge was the inability to return to the pre-2011 status quo. Conference organiser and scholar, Hanan Badr, aptly repeated Fouda’s memorable words in 2011: “Freedom is like death. You cannot experience death and return, and you cannot experience freedom and return.”

Fouda, among the more optimistic of the speakers, stressed how we should not lose sight of the goal that unfolded during the revolution’s 18 days. He reminded the audience how state-owned television channels were broadcasting a vivid scene of the Nile River – pristine and calm – while a few blocks away, Tahrir Square was rising up in its revolutionary glory. The contrasting scenes signified to him that the events of 2011 marked the fall of what the authoritarian state media had inherited from the 1950s and 1960s.

Fouda finally paraphrased John F. Kennedy’s words, “If you make professional journalism impossible, then you [the regime] deserve all the rubbish that is happening to you.” Here is the paradox of the regime’s repression: they realise their own media is losing credibility, and thus undermining the official narrative.

The journalists’ tireless efforts, coupled with the emerging cracks in the regime’s unsustainable endeavour, enables them to continue with their hazardous work, testing the boundaries, and, at times, breaking them. The future of Egyptian media freedom and professional journalism looked quite bright by the end of the discussion – but hopefully not only in Germany.