Originally published in Mada Masr, republished in openDemocracy

Arabic translation: رؤية مرعبة: عن خطط إعادة بناء منارة الإسكندرية

It’s no easy feat to restore the seventh wonder of the ancient world, but then along came modern-day Egyptian exceptionalism with its mega projects to obscure political and economic ills. The Pharos of Alexandria is now slated for resurrection after its demise in a powerful earthquake more than 600 years ago.

Today, the lighthouse icon adorns everything from the Alexandria Governorate flag, to the crest of Alexandria University, to public service logos, to wall paintings on elementary schools. One might argue its symbolic force arises from its invisibility — Alexandria’s cultural strength lies in the imagination. Reconstructing it might skew that imaginary past. But that’s the least of its problems.

In fact, Alexandria is at risk of being subjected to a commercial and geographical disfigurement by a project with no public accountability — and the silence on the issue is deeply troubling.

The odyssey of an idea

The story starts in 1978, when Alexandria resident and diplomat Omar al-Hadidi suggested rebuilding the lighthouse to then-Governor Fouad Helmy. The idea was not only welcomed, but pushed in the international media, capitalizing on then-President Anwar al-Sadat’s sky-rocking international stature as a result of the Camp David talks. However, a parallel development was underway, with one set of Alexandria’s cultural elites pushing for the resurrection of the ancient library. After 1981, the newly instated President Hosni Mubarak took on the latter with enthusiasm, elevating it to a global project, while work on the lighthouse dragged on in its shadow.

The lighthouse concept was a form of decentralization and a subset of a culture war with Cairo’s elites. The idea started innocuously enough. But the project was transitioning into the neoliberal age, with academics and cultural workers receding into the background and the rise of new money coming in its place.

When Mohamed Mahgoub took over as governor in 1997, he rightfully gawked at the 32 companies competing over the project, some of whom were suggesting to make it into a glass and steel building that would house a shopping mall, with laser beams instead of the traditional lantern at the top. Fortunately, Mahgoub cancelled the entire project for the then-foreseeable future.

But the idea was taken up again in 2005 by the Alexandria and Mediterranean Research Center (AlexMed) as part of a series of projects toward a vision to develop the East Harbor. The vision was proposed in the Alexandria City Development Strategy (CDS) process (2004-2008) “to assist to Alexandria Governorate to complete its City Development Strategic Framework for sustainable development and prepare for its implementation technically and institutionally.”

The East Harbor Development spent the duration of the lead-up to the 2011 revolution seeking funding opportunities. Post-2011 events saw an Alexandria that was in flux, and the project was restored again, now described as “a new definition for the relationship with the waterfront in coastal cities … rebuilding the old lighthouse in the area facing the library of Alexandria, located in Chatby, as well as building a residency hotel for tourists.” Alexandria’s cultural activists were too busy trying to save historic villas from being destroyed by the real estate mafia to worry about a theoretical project that was proposed before they were born.

But a surprise came in May, when Supreme Council of Antiquities Secretary General Mostafa Amin told the privately owned newspaper Youm7 that “members of the Permanent Committee of Egyptian Antiquities have approved an old project, submitted previously by the Alexandria Governorate, aiming to revive the lighthouse. The comprehensive studies and a final plan have been submitted to Alexandria’s governor for final approval.” The unexpected certitude of his statement set off alarm bells.

The project was unusually absent from the Egypt Economic Development Conference (EEDC) that was launched with great fanfare in early March 2015, even though the website of the General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI) — an affiliate of the Ministry of Investment, and the principal government body regulating and facilitating investment in Egypt — briefly describes the “revival of the old Lighthouse of Alexandria (Pharos)” project as “establishing a science museum reflecting the heritage value of the old lighthouse and a hotel, conference center, restaurants, concert hall and a marine club.” To date, the lighthouse project is listed with no budget estimation.

Mohamed Nabeel, the executive manager of Save Alexandria, notes that “all information announced so far was just to propagandize the East Harbor Project under the name of reviving cosmopolitan Alexandria, and hence attract investments. However, no information has been made available for the public about what their government is doing, no public participation that promotes accountability. And, overall, no transparency.”

This raises the question of which company will take on the lighthouse project. The governorate is supposed to open a call for bids within a transparent framework that guarantees integrity and public participation. But Nabeel believes that a top-down approach will probably be taken, and allocation will be given to “one of the state’s institutions or business sectors, such as the Arab Contractors. If the property belongs to the military, then the Military Engineering Authority shall handle the project, or the allocation of subcontractors might be applied.” Western architectural firms, however, have been behind a series of outrageous proposals to mutilate the city.

Alexandria Lighthouse … Why?

Not only do the proposed designs show the lighthouse containing shopping malls and a hotel, but the lighthouse is also part of a larger project to revamp the entire area. The 2007 report exploits the city’s Achilles heel of nostalgia and recognition: “The renovation of the whole Eastern Harbor with special emphasis on conservation, bringing into perspective the unique feature of dialogue of cultures symbolized in Alexandria’s cosmopolitan architecture. Evoking the past is experienced in integrating past and present grids in the new development, the revival of the academia with a new research facility, reviving the ancient Soma axis round the development of Silselah (peninsula stretching out from the library location), recreating the Pharos while highlighting the importance of the underwater archaeology and developing the Fort Museum. The concept emphasizes creating pedestrian experiences and establishing a relationship with the water edge while promoting leisure activities such as bathing, yachting, fishing or visiting the royal yacht Al-Mahrousa.”

It sounds beautiful on paper, and how could one say no to such a development, let alone not be charmed by the visual rending model? That is, until you realize this is about the venerable Alexandria. We have been down this path before — no flowery text and diagrams ever actually factor into the world of Alexandria’s power structures, complex social relations, economic inequity, informal economy, the fate of fishermen, unearthed archeological treasures and so forth. Nabeel raises the concern that the implementation of Phase I & II (2004-2009) of the CDS process has shown that no proper monitoring or evaluation has been carried out, no positive implications and, most crucially, no public participation.

Figure Two shows a 2009 design by the Chicago-based architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP that renders Alexandria in the year 2030. This is the same company that designed the Burj Khalifa, and it notes Egypt’s Culture Ministry as its client (they also report to be leading the planning of Egypt’s new capital city). There is not a single Alexandrian of any persuasion that I have shown these images to who hasn’t given me a look of horror in response.

Egyptian and foreign-based firms have an obsession with slick, futuristic, cutting-edge designs, forgetting that maintenance is not one of Alexandria’s assets. Alexandria could always veil its lack of maintenance and infrastructure behind its rustic, antiquated and historical image. But anything with a futuristic public planning streak would suffer from poor maintenance.

The politics are bigger than the lighthouse

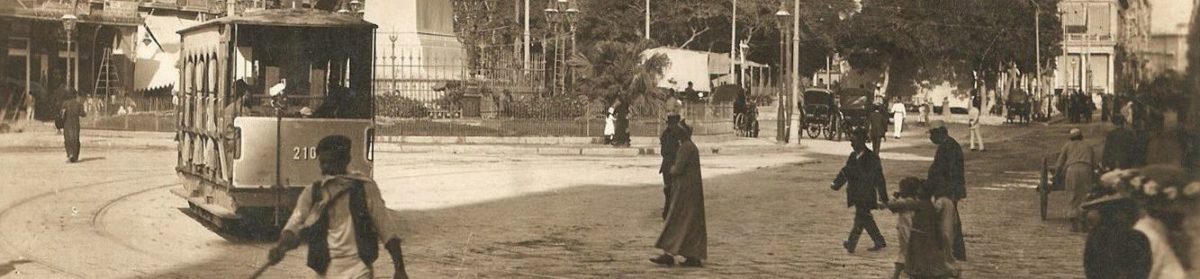

Since the 1990s, Alexandria’s public spaces have been subjected to an ideology of revivalism. This involves resurrecting cosmopolitan-era fixtures like gas-light lamp posts, and placing statues like Alexander the Great and Cleopatra in public space. The crowning achievement of revivalism was the unveiling of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in 2002. While revivalism brought some benefits, it has more to do with political branding, in which the state imposes a narrative from above upon the public. Furthermore, these nostalgic motifs frequently act as a guise for neoliberalism. Historically, Alexandria is treated like the political laboratory for Egypt’s reckless economic experiments.

Had the governorate been sincere about revivalism and preserving the heritage of the city, it would have saved countless monarchical-era villas from destruction. Preserving what we already have counts far more than any lighthouse bells-and-whistles project. But the reality is not about amplifying Alexandria’s rich cultural history as much as it is about what aspects of its history can be vulgarly commercialized at the expense of the public good. There is not even a proposed lighthouse design that will stay faithful to its ancestor of antiquity, which was built out of limestone, granite and white marble. Rather, it will be something resembling a watered-down version of Burj Khalifa.

One investor proposed “relocating” the iconic Citadel of Qaitbay to build the lighthouse in its place. The thoughtless idea was quickly quashed. But it shows what the city is up against.

“Capitalism talks here,” says Islam Asem, director of the Tourist Guide Syndicate. “If these investors could destroy the pyramids and build something profitable in its place, they would not hesitate for a moment.” It is largely faceless investors that are sitting on boards making decisions, Asem laments, not academics, cultural workers and UNESCO.

Asem states that the proposed lighthouse location would further weaken the grounds holding up the fragile citadel, and destroy the Greco-Roman ruins under the seabed. This is not to mention the aesthetic disruption of the Alexandria skyline by having a modern building next to the citadel. Asem says it’s better for the project to be constructed far away, in Montazah or Aboukir.

Nabeel also supports this view.

“A metropolitan city cannot be reduced to its city center,” he says, warning that under this kind of development plan, Alexandria “will see more urban segregation and, hence, urban rebellion.”

That urban rebellion was a familiar trait of the city through the sporadic, pre-revolution upheavals of the 2000s that were spurred on by the privatization drive. This can only worsen if the city’s soul is further compromised.

The inability to develop a strategic vision for the city is reflective of the city’s high politics. Any new governor is usually initially met by Alexandria’s civil society with hesitation by default, due to a lack of an electoral mandate. This was the case when President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi appointed Hany al-Messiry governor in February 2015, especially because left-wing activists were concerned with his free-market economics philosophy. However, a number of them allowed him breathing room for a few reasons. He was from Alexandria, which fulfils the basic providential nationalism criteria. He was a civilian, and not from the military. He was perceived as refined, due to being educated abroad and international exposure. Most importantly, he took a favorable approach to working with civil society.

But such strengths were exploited by different groups and power factions. The media started attacking Messiry for bringing his wife with him to meetings. Then hyper-nationalists took issue with him because he was not from the military. Security entities were calling up civil society workers to “discourage” them from meeting with the governor.

This all came to a head when an anti-governor protest was held in late May to protest Messiry’s dual nationality (he holds American and Egyptian citizenship). Demonstrators chanted, “Go out Messiry, Alexandria is free” while burning the American flag. One source told me the protestors were hired by private contractors after the governor refused to issue new building contracts. It’s notable that the Protest Law was not implemented for this demonstration, and no one was arrested, raising questions of security complicity.

Marianne Sedhom, who co-runs Iskanderya mabatshee Mareya — an environmental initiative that roughly translates as “Alexandria is no longer pretty” — highlights the obstacles to governor faces. For example, when Messiry issues a decree to halt work on, or to destroy, an illegally constructed building, corrupt elements within a district board will issue building permits to allow more illegal buildings to go up, she claims.

Such is the toxic climate out of which the lighthouse, or any development for that matter, will emerge. This is not to write off the lighthouse as a bad idea. The lighthouse has the potential to be a powerful uniting public icon bridging the cultural imaginary between the past and the present, solidifying civic identity, attracting tourists, and more. But this is only if it is done appropriately, with transparency and broader public discussion on the matter. No lighthouse is better than a badly planned lighthouse that violates aesthetics and social, heritage, communal and environmental factors.

The historical magnitude of rebuilding the lighthouse requires it to be the result of a clear vision and coherent civic narrative. It should not be built to resolve or eclipse existing divisions. If modern Alexandrian history is any indicator, it will become not the symbol of a communal spirit, but the symbol of excess and a visible target of rage.

There is a lesson to be learned from the unveiling of the ancient lighthouse in 247 BC. After 12 years of construction, the architect Sostratus was under no illusion that he had to dedicate the new monument to Ptolemy and his wife — but he would not allow history to forget his hard work and the people it was intended to serve. So he engraved his words in the stone, then he placed a plaster plaque etched with a dedication to the Ptolemies over it. With time, wind and sea salt ate away at the plaster. Long after the monarch and the architect passed away, the plaster decayed and fell apart, revealing his words: “Sostratus, son of Dexiphanes the Cnidian, dedicated this to the Savior Gods, on behalf of all those who sail the seas.”

With time, the narrative that emerges out of this project might not be the one that the state had intended.