Published in the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy

“Would you allow your unmarried daughters to live alone in their own apartments in Cairo?” This was the question asked by American journalist Milton Viorst to the late Naguib Mahfouz in the 1990s. The legendary Arab novelist replied that such a circumstance would not be acceptable, as it simply would not look right.

Mahfouz did not invoke a financial, safety, or even religious motive to underpin his reasoning—in effect, he made the “what would people say?” argument, which permeates Egyptian society and holds hostage any and all statements and actions to the court of public opinion, consequently warping people’s reasoning.

In light of the increasing harassment of bearded men in Egypt, I called a relative of mine out of concern for his safety. His first response to my inquiries was, “Can you imagine what the Americans and British are saying about us now?” He found this conjecture to be a more pressing issue than his personal safety and the safety of others. Indeed, every relative with whom I speak cannot help but ask, “What is the West saying about us? Make sure you tell them the truth!”—as if I had a monopoly on the information coming out of Egypt (and the rest of the world had no access to the Internet).

A sort of obsessive-compulsive public-image disorder is sufficiently widespread that it crosses social and class lines in Egypt. At the heart of everyday decision making lies the anxiety of what society may think rather than any consideration of the merits involved. This hyper-sensitivity to public opinion is present on multiple levels, ranging from how society will judge the individual to how the international community will judge Egypt. For the latter, this sensitivity is in no way a constructive one that encourages appropriate responses, such as tackling sexual harassment and human rights abuses. Instead, it combines with an entrenched political and social schizophrenia, leading to a pattern of denials, conspiracy accusations, and selective historical reminders whenever sensitive topics are discussed –“Did you not know that Egypt loaned money to Great Britain during World War Two? Or that Egypt used to provide the Kiswah (covering cloth) for the Kaaba in Mecca?” There is an accordingly disoriented sense of priorities for the state and individual.

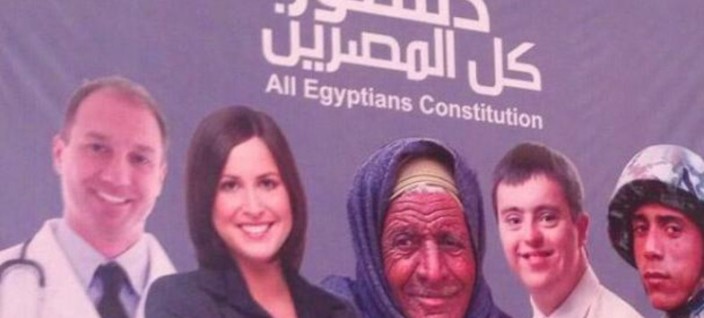

You would think that the deaths of protestors would lead to the prosecution, if not at least the resignation, of the responsible public officials. To the regime, however, such deaths are not as serious asDecember’s banner fiasco, which marred the promotion of Egypt’s new constitution by featuring foreign, stock-image faces and an Arabic spelling mistake. This public relations embarrassment before the world saw State Information Service head Amgad Abdel-Ghaffar resigning and the designer of the banner being “penalized.” Yet, the Interior Minister is still in his position. Banners, clearly, make Egypt look bad—arrests and killings do not.

Such a climate transforms Egypt’s political sphere into a theatre of the absurd, enabling the recent, extraordinary scandal of the military “invention” that allegedly cures Hepatitis C and AIDS. This worrying development is a reflection of the authorities shifting into desperation mode, trying to improve their image by demonstrating any sort of unprovable achievement. This is so even though it comes at the expense of damaging the reputation of Egyptian doctors and scientists and, worst of all, giving false hope to millions of impoverished patients across the country who are unlikely to see through the political smokescreen.

What about the world?

One of the most common tactics to justify the public image disorder is to employ the logical fallacy of tu quoque, Latin for “you, too,” which has become increasingly rife in everyday language. Criticism, constructive or not, when levelled at Egyptian policies or social ills, is rejected solely on the basis of the critic’s perceived inconsistency, not the argument or position itself. While many critics of Egyptian matters may indeed be hypocritical and inconsistent, this form of ad hominem attack still does not invalidate their arguments.

Following the horrific 1997 Luxor massacre, which saw 62 people, primarily tourists, killed, an Egyptian official came out before the international press, grinding his teeth and insisting that this happens everywhere else in the world. Such is the function of the time-honored deflection of responsibility that we still hear daily—“It happens around the world, not just in Egypt!”

Sexual harassment rampant in Egypt? That is fine, it happens in India too. Buildings and bridges collapsing in Alexandria and Cairo? Not to worry, Bangladesh has it worse. Pollution choking Egypt’s capital? Have you even seen Beijing? Foreign journalists illegally incarcerated in Tora prison? What about Guantanamo? Was that a massacre of a couple of hundred demonstrators in Rabaa? Well, it’s our war on terrorism, just like yours.

Egypt might be burning, but the only response it seems to have is to deflect attention away from the flames. Tu quoque or not, it is clear by now that reason and logical arguments have been pushed to the margins of political discourse in an Egypt where a stork and muppet can be investigated for conspiracy, terrorism and espionage.

The politics of visual piety

The public image disorder can also be seen in the way that religion plays a powerful role in Egyptian society and the value attached to being seen to adhere to religious norms reflects the society’s abiding concern for what others may say.

Once, while attending the Friday sermon at a Cairo mosque, I heard the imam express disappointment that youth were not attending the fajr (dawn) prayer. After a number of conversations with the devout who were not in attendance, it did not take me long to figure out that, apart from the stay-up-and-sleep-in behavior common to the Egyptian lifestyle, the societal incentive to be seen attending the fajr prayer is significantly less than that which is attached to the weekly, congregational Friday prayer, an event that not even a bank robber would miss.

This is neither to dismiss genuine convictions nor to deny the fact that Friday prayers—in the congregational manner—are considered obligatory in Islam. Rather, it is to show that the social element attached to public displays of devotion is so overwhelming that it skews the degree of religiosity in Egypt, widening the gap between beliefs, statements, and actions.

The rule of former President Hosni Mubarak gutted the official political-administrative sphere, and the religious sphere grew in scale as a form of societal empowerment and opposition. Women increasingly donned the veil, the zabiba (a mark on a Muslim man’s forehead from frequent prostration) mysteriously proliferated, and the crucifix became more prominent on Copts. This phenomenon at least partly explains why the Muslim Brotherhood confused Islam with Islamism and believed that their form of identity politics could just be rammed through the public sphere without any semblance of negotiation

Women, religious or not, receive the harshest judgements regarding personal dress, whereabouts, and life decisions in general. Every deviation from the behavior associated with that of a mohtarama, or a “respectable woman,” is discouraged by families concerned by the social impact of what people may say about her.

Since the revolution, there has been a growing trend of Muslim women removing their veils. Those with whom I have spoken largely argue that they have neither become any less religious nor comprised their principles, and they stress the freedom element involved in the decision to wear the veil. Strangely enough, these women are not admonished with “God will disapprove” statements; they instead encounter responses focused on society. One young woman who had recently removed the veil remarked, “I lost so many friends who felt that I was letting them down, that I was no longer the person they thought I was. The public was unforgiving; they had certain expectations of me that were defeated.” Equally, it is not unusual for women who wear the veil to receive compliments and criticisms that revolve around fickle public opinion, not divine ordainments.

The state’s extreme makeover

However, there is a deeper and more sinister side to this disorder. Inevitably, as national image becomes conflated with national security, this disproportionate concern with perception over reality helps to pave the way for public policy to effortlessly make inroads into the private social sphere. Taking advantage of a public already well-practiced in focusing on social perceptions, the state sets the tone of this self-image affliction by accusing its “opponents” of nonsensical crimes such as “spreading false news,” “damaging Egypt’s image abroad,” “insulting the judiciary,” and “breaching national trust.” Looking at the names of these “crimes,” it is almost as if the Egyptian state has feelings that are easily hurt.

Egyptian’s private spheres are continually violated rather than protected, particularly with regard to bodily integrity such as an individual’s safety, privacy, religious freedom, liberty, and protection from arbitrary arrest and detention. This is a key factor behind the establishment of Hossam Bahgat’s Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, human rights in Egypt have largely focused on the public sphere, not the personal sphere (and even in the former, they are struggling against a rising tide of state authority). The private sphere is where one experiences everything from silent violations, like one’s religion being placed on national ID cards, to the more menacing trend of neighbors ratting out neighbors to the authorities—your business is everyone’s business when your actions are seen to reflect on the state.

As with many problems, one may need return to childhood for an answer. Here, the 1971 collection “The Black Prince and other Egyptian Folk Tales,” by Ahmed and Zane Zagloul, may have the answer.

In one of the stories, a father decided to teach his son a valuable lesson due to the son’s frequent response of “what would people say?” in regards to his father’s disciplining him. The father mounted a donkey and told his son to follow along on foot in the market place. The crowds immediately responded: “Do you have a rock instead of a heart, you merciless man? How do you have the shamelessness to ride while that poor boy of yours runs along behind?”

So they switched places, with the father now following the boy and donkey on foot. An old man yelled out: “I do declare! If that ain’t the way to bring up an ingrate. Yes sir-ree, if you want no respect from your boy, that’s the way to get it…What are fathers made of these days, I’d like to know?” Finally, they both mount the donkey only to be jeered at by more onlookers who are never happy with whatever the father and son do. The ending sees two police officers taking the father and son first to the police station, then to the madhouse. “This, my son,” the father says, “is the result of troubling yourself over what other people would say.”

Egypt’s own written traditions scream against the excessive “what would people say?” syndrome, as it compromises one’s integrity and leads to actions that are not reflective of an individual’s true self. It shuts down debate, separates one from exposure to new ideas to improve the human condition, renders self-expression perilous, and makes hypocrisy and double-standards into accepted norms. The end result is a society that is living a lie as the world moves on, with or without Egypt.

Now vs. Then

Dr. Nawal el-Messeri Nadim did her dissertation on Mahfouz’s Sugar Street. She makes the case that, in Egypt’s culture of the alleys, what people think of you trumps your individual achievements. That is to say, an alley-dweller is not just a person; he or she is part of a social network that is final arbiter of his or her value.

Yet, one of the Egyptian revolution’s secondary goals has been to break this kind of social network, particularly its harmful elements. Despite the revolution’s apparent regression, it has had remarkable success in the cultural arena, which has witnessed a massive expansion in the space that is open for creativity, from new forms of street art to the wide popularity of satirist Bassem Youssef. Such openings reflect a force against which the state will have to reckon.

It will be some time before the public space renegotiates the question from “what would people say?” to “what would the future say?” Historians studying the current period in Egyptian history will undoubtedly find its events beyond description and understanding.

One only hopes that the obsessive-compulsive image disorder, along with the many other disorders that are a part of this increasingly fascist-leaning environment that is pushing people into the folktale’s madhouse, burns out before it burns the rest of the country with it.