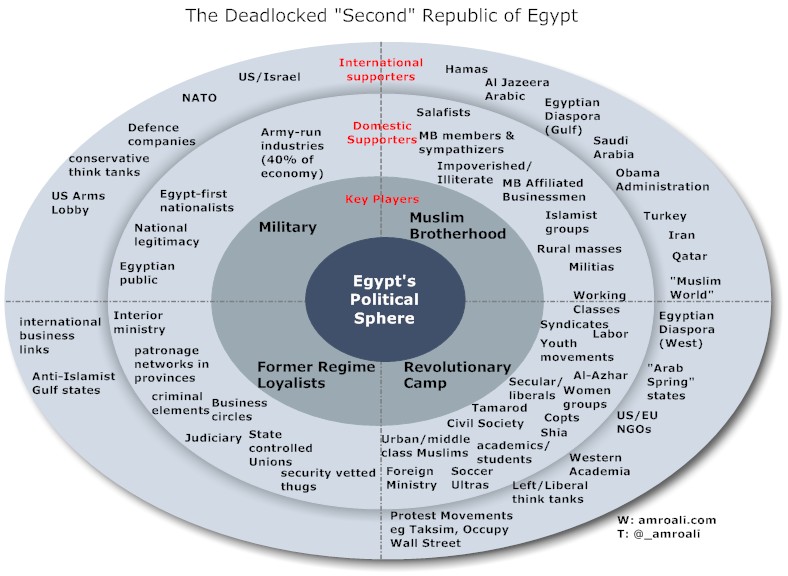

We have come to the current crisis that sees an Egypt that is politically stillborn and has been unable to resurrect the old regime nor can it establish a new one. What I have attempted to do is illustrate this by examining the constellation of actors that are contributing to this deadlock. The plotting of different groups on the map is based on news data, policy statements, interviews, and my experience with Egypt’s urban politics. At this stage it is not intended to be a scientific diagram nor is it an exhaustive list of all players. It is only to illustrate the gravity of the deadlock that has brought us to 30 June.

The former regime, according to Hazem Kandil, rested on a power triangle that consisted of an uneasy partnership between the military, security sector (interior ministry) and the political establishment. The 2011 events disrupted this balance resulting in the enhancement of the military’s role and saw former regime remnants, Islamists and revolutionaries seeking to fill the political vacuum.

1. Military

The military is the dominant actor and backbone of the transition, much of the current political rival suspicions and deadlock can be traced back to the military’s opaque decision making and centralisation of power when it was governing the country in the interim period. While the military is relatively de-politicised, it is nonetheless desperate to preserve its economic privileges and ensure the country does not enter a “dark tunnel” as General Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi puts it. This partly explains why it looked more favourably upon the Brotherhood who were less likely to dismantle the political economy than the revolutionaries were.

el-Sissi may have inadvertently emboldened the revolutionary camp by implicitly warning Morsi’s supporters that the military will step in if people are attacked during the planned protests.

Yet the military is still reeling from having its prestige damaged during its 2011 and 2012 rule, and it is unlikely to see a role for itself in the political scene even after today’s expected coup d’état. The military has never viewed its purpose as a force for change.

Domestic Supporters

The military is the most popular with the Egyptian public, and whatever animosity existing towards the generals, seems to have significantly diminished under one year of Morsi. The Egyptian opposition is gambling that the military will not want to rule Egypt and that it will form a presidential council.

The military draws its legitimacy from being the guardians of the state, as well as founding myths and narratives of the Egyptian republic elevates the military. Also their strength is drawn from the economic leverage they have over the economy, up to an estimated forty per cent.

International Supporters

The military’s international support is well established, and the US relies on it as the principal actor to protect the Camp David treaty with Israel and it is the beneficiary of annual US military aid. Egypt’s military elites draw support from a wide range of state actors, military complexes and conservative bodies.

2. Former Regime Loyalists

Mubarak’s former regime survived in various incarnations, while not seeking to regroup or become a political force in any meaningful way, they have played an obstructionist role during the Morsi presidency; so in a sense, Brotherhood accusations of policy hindering thrown at former loyalists is not entirely unfounded. However, the Brotherhood shoulder a large part of the blame for this. This problem was foreseen two years ago, and the revolutionary camp made demands for Morsi to form a broader political coalition to tackle institutional reforms. The Brotherhood would have none of that.

Domestic Supporters

The Interior ministry is the lynchpin of Egypt’s problematic transition that is seeing security forces behave at times as mercenaries as they strike and break deals with Egypt’s political actors, and strategically delay their arrival at flashpoints. Moreover, as I noted in my April article for the Atlantic Council “The buck dies here: why Egypt’s Interior Ministry refuses to be tamed,” an identity crisis has developed in the interior ministry in which it is “caught between a hatred for the revolutionary camp, a lackluster love for the Brotherhood-run government, a public that mistrusts them and a military they perceive as having abandoned them or their patron in the form of Mubarak.”

The revolutionary camp is cozying up to former regime loyalists in what could be a marriage of convenience to confront the Islamists.

International Supporters

It is understood that former regime loyalists have overseas bank accounts, and supporting evidence indicates a trail from political but mainly criminal activities in Egypt’s cities that can be traced to bank accounts in Dubai and other parts of the world. (This is an under-investigated topic and I urge my colleagues to take it up if they can)

3. Muslim Brotherhood

The 85 year old group excel in organisation and mobilisation but has greatly suffered a credibility deficit over the past year. It holds onto power by a mandate, but the ‘ballotocracy’ has seen its political arm and its president Morsi engage in reckless political behaviour that has brought Egypt to its stalemate.

Domestic supporters

Its domestic support base has rapidly been shrinking, in March, it lost the elections at universities as well as Pharmacists, Doctors, journalists syndicates.

The Brotherhood’s support base tends to be less diverse. The Salafis while have shown tendency to oppose the Brotherhood lately, it is not clear whether this will translate as a vote for non-Islamist candidates. At the very least, Salafists have demonstrated a more pragmatic streak, and if anything their placement in the diagram is to indicate support for the Islamist project under whoever will carry the mantle.

International Supporters

The international support is various and I’ll explain only two. The Obama administration takes a more pragmatic approach of supporting the Brotherhood as a partner, given the opposition have not shown themselves to be an organised and credible political alternative.

The Muslim World is a problematic one and not an easy one to define, but it is reflective of how Egypt is viewed. Morsi appears vastly different internationally than he does domestically. This is partly due to the romanticised view that Egypt holds as the head of intellectual Sunni Islamic world.

4. Revolutionary Camp

Larger, diverse but disorganised, the revolutionary camp dominates the gravity centers, particularly the Cairo-Alexandria axis. The latest events sees them stretching out into rural Egypt, but not because of any organisational clout on their part, but due to the miscalculations of the Brotherhood.

Domestic Supporters

Importantly, they have the support of Al-Azhar, this is interpreted based on opposing statements to the Islamist camp. Having the 1200 year old institution on side is quite critical as it undercuts the legitimacy of the Brotherhood’s attempted monopoly over the Islamic faith.

Placing the foreign ministry in the this group may seem strange, but the ministry often stood out as the most professional and left-wing during the Mubarak era. They have also openly opposed the Morsi presidency, and many refused to hold the constitutional referendums in their embassies abroad. One could even go further and say that other key ministries such as information, culture and education (not indicated on the diagram) hover between former regime loyalists and the revolutionary camp. If anything, they are not in the Brotherhood’s camp despite ministers from their organisation leading it.

International Supporters

The international cheerleaders are often the ones aiding in positive coverage of the revolutionary camp and the ones that indirectly cause tension between respective Egyptians and the regime.

Final thoughts

This is currently a working draft that will soon appear in Jadaliyya and I will further refine the diagram as the weeks go by, but the purpose is to highlight that such a deadlock with ministries, strewn in one camp or the other, cannot produce a cohesive political will or form a new political establishment. An interior ministry that cannot be reformed will contribute to the environment of insecurity.

What in part brought us to this is not just the Islamists failure of policies, but the rapid erosion of Morsi and the Brotherhood’s legitimacy in public discourse. Their gamble at abandoning key players and the urban gravity centers of Cairo and Alexandria meant they will remain an organized but fractured political actor. In order to achieve tactical objectives (such as elections), Islamists were forced to become more beholden to the Brotherhood’s meddling Guidance Bureau, seek the services of the Brotherhood militias (like at the presidential palace early in December), appeal to Salafist allies, fan the flames of sectarianism, and play the identity politics card. Whereas tactical objective may be achievable, the trajectory employing the above inevitably destroys their strategic longevity as a credible political player. Morsi and the Brotherhood could have earlier on chosen to form broader coalitions to build up political capital in order to heal a polarised nation and reform the stubborn institutions, instead they chose a course of action that put them past the point of no return. The rebellion campaign of 30 June is to force a readdressing of the overall deadlock. Today is the anticipated coup d’état, Egypt enters a new and unknown phase.