Published in openDemocracy and Egypt Monocle

Once when a Saudi diplomat whom I knew greeted me as Ostaz (Mr) and I replied in kind with Ostaz, he shouted “Doctor!” I was taken aback at the response. Did I miss something here? The Arab world’s social fixation with ‘doctor’ titles can really be burdensome if at times comical.

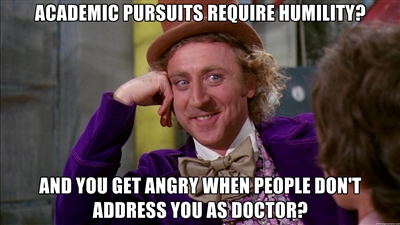

When Egypt’s TV satirist Bassam Yousef opened the floor for questions following his opening peroration, a number of Egyptian audience members started off with, “I’m doctor so and so”. Yousef remarked, “we seem to have a lot of doctors in the house today” to the laughter of the audience. At a Cairo conference on the Arab uprisings earlier this year, a female Egyptian academic pleaded with the audience during question time in what was only a semi-joking manner: “I worked so hard for my PhD, so the least I can ask of people is to call me doctor.” This was cringe-worthy, given the number of overseas academics in the session who could not care less if you addressed them as doctor.Yes I can hear the cries already, “This happens all around the world, not just the Middle East!” Sure, the old guard of scholarly circles in Italy and Germany get irked if you fail to address them as such, but it is on the wane. I’m no blind egalitarian that believes titles should be done away with. There is a time and place for titles, such as first meetings, formal ceremonies, application forms and business cards. I’ll use it more out of respect for an elder than anything else.

But we are talking about the abuse of the title ‘doctor’ to the extent that it even makes it into people’s signature, caller ID’s. Merely registered PhD candidates get called doctor, and the expectation that the title confers upon someone is an all-knowing command of any subject. You hear statements like, “I have a PhD in veterinary science, but I do know a bit about the changing Middle East socio-political landscape”.

One particularly galling afternoon, an Arab professional continually addressed his own wife as doctor at a barbeque. I did not know what the Arabic equivalent of “Get a room” was; the other less than safe alternative was to examine the possible multiple uses of those rotating skewers. A baffling scene unfolded when in a room of a dozen Saudi, Egyptian, Palestinian and Jordanian doctors, everyone referring to each other as doctor made it difficult to keep track of who was referring to whom.

Randa Abou-Bakr, a professor at the Department of English Literature at Cairo University, claims the need to keep titles to establish cordial teacher-student relations but adds, “I just feel it’s awkward when my colleagues or some casual acquaintance address me so [as doctor or professor]. I find it ridiculously formal. In Egypt, or at least at Cairo University, there are some departments with more ‘liberal’ traditions than others. In our department…the relationship between colleagues is rather casual.” However, take a stroll through the grounds of the hard sciences in the Arab world, and you hear the title doctor thrown around so much you would think it was an emergency ward with injured patients seeking the nearest help possible.

People who overemphasise their titles set off alarm bells for me.

One Kuwaiti delegate informed me of his wish to undertake doctoral studies. When I enquired into his research interests, he could not convey any compelling motivation and the only thing I understood was the “prestige” it entailed and the “promotion” he would receive just to be called “Doctor.” From having counselled hundreds of Gulf students studying in Australia in the past, this was a tell-tale sign that a student might be at high risk of plagiarism and ghost-writing when they commence their programme. The Saudi “DOCTOR” diplomat was the end-result: he received his PhD from a UK university but could hardly write a coherent English sentence.

In fairness, they are responding to the social structures of their societies that puts the love of research in the back seat so that wasta (connections),symbolism, and stature take first precedent. I’m pinning my hopes on the younger generation who don’t seem to exhibit the same rigid and formalistic expectations as their older peers. An overarching shift in the mindset is needed to return scholarly pursuits to the humility and curiosity that characterised the Arab spirit of enquiry for centuries.

Titles were certainly the norm, but there was also modesty. Unlike one engineering professor at an Egyptian university who told my friend’s class: “There is God in the heavens, and there is me on Earth.” Makes you almost want to insult him, by, wait for it, calling him by his first name.

And if you think this is confined to academia, spare a thought for gym-goers. At an Alexandrian gym, the instructor was peeved that I did not address him as “captain”, turned his back and walked away.