Published in openDemocracy and Egypt Monocle

On a conference visit to Rome a few months ago, I was taken aback by what I saw upon my arrival at the main train station, Roma Termini – out on the street was a homeless man, in torn, dishevelled clothes, reading a book. The sight in some ways entranced me. Here was a man who had lost everything in life, but had not lost his dignity to live and re-live through the written word.

I found myself bleakly registering the contrast with Egyptian university graduates who will rarely pick up a book following their formal education. Forget leisure reading, they would no more think of taking out a book in a cafe as taking out a gun. Ask a young Egyptian why don’t you read, and the response is, “I only read if I have to.” In other words, if it is work-related or an obligatory part of some curriculum.

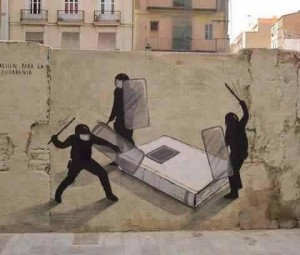

It is in this context of a defanged reading culture that police raided the book sellers on the historical Nabi Daniel Street in Alexandria – the city that spawned one of the wonders of the world, the ancient library of Alexandria. The street – where I could pick up a copy of a 1960s Time magazine or some other yellowing Egyptian periodical – strewing books all over the pavement and sending shockwaves throughout the literary world followed by accusations of Muslim Brotherhood-style censorship. Contrary to what media outlets reported and activists tweeted, this was nothing to do with Brotherhood censorship. It was about cracking down on street vendors who cause street congestion. After all, Islamic books occupied a portion of the desecrated books, countless (non-book related) street vendors were affected by the raids, and fixed book shops were not touched. The evidence is clear.

Nonetheless, this episode is a pointer to a troubling aspect of a widespread mindset – the contempt for books so eloquently anatomised by Khaled Fahmy in his sobering piece, The Tragedy of Books in Egypt.

In fairness, Egyptian society is also battling the cultural wasteland that was left under Hosni Mubarak. Under thirty unimaginative years, the impulse to read declined to such an extent that book stores resorted to selling stationary. The goal of life was merely to survive, not to thrive.

Yet I have reason to be optimistic.

Following my return trip from Rome back to Alexandria, I set off to ask bookstores how sales differed now compared to prior to the revolution. Many reported sales have gone up on political and history books. Interestingly, outside of the Egyptian publication industry, personal development books are greatly increasing. Robert Greene’s “The 33 Strategies of War” has been translated into Arabic, reflecting a growing market demand on the topic of empowerment since the revolution.

One avid reader pointed out that reading has been diversified and someone holding a book in a café may have given way to PCs, e-book readers, smartphones, and electronic gadgets that are replacing traditional books.

The reincarnated ancient library, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina is also shaping attitudes today. The library is trying to compensate for the dysfunctional education system that has produced a generation of rote learners rather than critical thinkers by holding countless seminars, debates, workshops and symposiums on how to move Egypt forward.

The library has become an agent of socialisation. Like mosques and churches, it is being adopted into the social structures where rules and norms are slowly being reinterpreted and reconstituted in young people’s understanding of their place in the new Egypt. The by-product is an increased self-awareness of the value of reading and the cultural arts.

Yet Egypt is much bigger than Alexandria and the recent book raids highlights the issue of law enforcement practices that are reflective of a police generation lacking any trace of sophistication or subtlety, and, like every other hangover from the previous regime, in desperate need of reform.

Nor should the recent incident be a reason to let down one’s guard against any creeping Brotherhood censorship attempts. If anything, it should make one more vigilant.

That homeless person in Rome brought Mark Twain’s words to mind: “The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can’t read them.”