Article published in:

Ahram Online, openDemocracy

In the nascent days of World War II, French Premier Paul Reynaud remarked to General Pilippe Pétain: “You take Hitler for another Wilhelm I, the old man who seized Alsace-Lorraine from us and that was all. But Hitler is Genghis Khan.” Reynaud’s subtext was clear: if you wish to use the ‘history repeating itself’ line, use the right history.

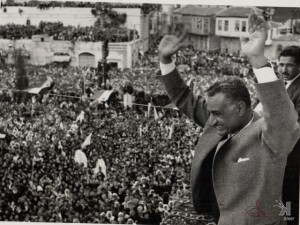

Using history as a guide, no matter how well intentioned, is often fraught with high risks: outcomes can vastly diverge from the history lesson sought initially. For example, the lesson of Munich (1938) ‘not to appease dictators’ set the tone for the 1956 Anglo-French confrontation with Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser in the Suez War. It turned out disastrous for the protagonists and left the young Egyptian leader with all the claims he might need to a political and moral victory.

Using history as a guide, no matter how well intentioned, is often fraught with high risks: outcomes can vastly diverge from the history lesson sought initially. For example, the lesson of Munich (1938) ‘not to appease dictators’ set the tone for the 1956 Anglo-French confrontation with Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser in the Suez War. It turned out disastrous for the protagonists and left the young Egyptian leader with all the claims he might need to a political and moral victory.

Egypt today has a semi-emasculated Islamist president, a reinstated but uncertain parliament, the strong presence of the Muslim Brotherhood, an overbearing military council, a restless public, all mixed up with an economic crisis. Questions are being asked, is Egypt going to become like 1979 Iran, 1991 Algeria, Old model Turkey, 1999 Pakistan, or even 1954 Egypt?

Isn’t it possible that 2012 Egypt may be just that, 2012 Egypt – with all its idiosyncrasies, rotation of actors, socio-economic uncertainties, Pan-Arabism from below, digital youth; in an era of globalisation and changing geo-strategic realities, all the while taking into consideration the unique historical forces that shape these factors?

It is one thing to discern trends in history and attempt to learn from the past in order not to repeat similar mistakes. Yet another is to carpet-bomb Egypt with the ghosts of “history repeats itself” templates.

David Hacket Fischer in his 1971 book Historians’ Fallacies notes the “Didactic Fallacy”; the extraction of specific lessons from one historical event and their literal application to contemporary problems without regard to differences in time, space, and circumstances. The Didactic Fallacy is ripe through the comparisons to Egypt we hear of lately.

The theocratic Iran analogy is far-fetched despite the rise of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and the Morsi presidency. Egypt’s military establishment were old enough to remember the Shah’s military playing a minimal role in the 1979 uprising as various Iranian factions battled each other out for control of the revolution. For all its faults and counter-revolutionary streak, the Egyptian military has been the backbone of the transition and acts as a check on the rise of a singular radical force.

Economic considerations will drive political imperatives. There are vast differences between Iran’s oil exporting economy and Egypt’s service-driven economy. Iran does not require the goodwill of the international community as customers are in plenty supply who will buy Iranian oil. This does not work for Egypt as self-sufficiency is in rare supply and not an option the new Egyptian government can fall back on. Hence Egypt’s strengths in tourism requires a positive image and the shunning of ultra-conservative laws if tourists are to even set foot in Egypt. Moreover, the dependency on tourism, Suez Canal revenue, cotton exports, investments, aid, Egyptian expatriate remittances and so forth, places Egypt as a crucial node in the globe’s economic and social inter-connectedness.

Algeria is the favoured analogy as of late, the country that was plunged into a bloody civil war in the 1990s following cancelled elections by the military to prevent an Islamist victory. This is despite countless differences between the two countries: Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and Algeria’s Islamic Salvation Front, military establishments, sources of legitimacy, socio-economic realities, international stakeholders and very different contexts. Interestingly, it seems difficult for the doomsday commentators to contemplate the optimistic version of the ‘history repeating itself’ line. Egypt, for all its past repressive authoritarian regimes, has not experienced civil wars and one would be hard pressed to find, let alone hear of, a mass grave. Yet Algeria’s tragic loss of over 100,000 lives is supposedly the outcome awaiting Egypt.

Nor is it 1954 Egypt, when the military torpedoed any prospects of democracy, and clamped down on the Muslim Brotherhood and other opposition forces. Ahmad Shokr provides a compelling refutation in Jadaliyya of this comparison that preoccupies many people in Egypt. Shokr notes that unlike 1954 Egypt and the Free Officers, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) is not as politicised (although desperate to preserve their privileges), does not see itself as a force for change, lacks mass public support, all in a post-colonial context where attitudes towards representative democracy are favoured and political mobilisation is broader.

Finally, the problem of the history repeating itself fallacy is that it is the silent nightrider of fear that feeds into a vicious cycle that rattles stock markets, bulges emigration queues, foments societal suspicions, reinforces orientalist perceptions, and sustains the Arab world’s ‘healthy’ conspiracy industry – often before any reason for fear presents itself.

What the past year and a half illustrates is that in the absence of a decisive success by a singular force that could author a hegemonic order, Egypt will continue to see the persistence of street battles, protests, sit-ins, and compromises between SCAF, the Morsi presidency, former regime remnants, emerging political players and the popular masses who continue to rival the establishment in setting the pace of the transition and widen the parameters of the debate. This seems to be the script of the extended revolution. If so, Mark Twain’s words might be more applicable here: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”