By Amro Ali:

It was Lenin who once said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”. After decades of stagnation under Mubarak, there could not have been a more fitting description for the events in Egypt of early 2011.

It was Lenin who once said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”. After decades of stagnation under Mubarak, there could not have been a more fitting description for the events in Egypt of early 2011.

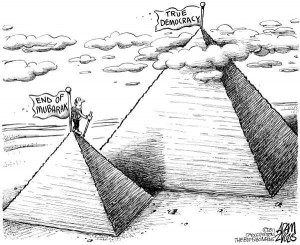

In 18 days, the Middle East experienced a geo-political earthquake. President Hosni Mubarak was successfully overthrown after 30 years in power. Yet what made the events spell-binding was the relative non-violent nature of the protestors, the all-inclusiveness, Muslim-Christian unity, and the communal spirit – an inspiration to the world. After the Pyramids, Tahrir Square became one of the most famous Cairo landmarks and was elevated to the hall of famous squares alongside Tiananmen Square.

After the January overthrow of Tunisia’s leader Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Middle East experts were appearing and proclaiming that the Mubarak regime would not follow the Tunisian path. Yet what so-called experts and intelligence services could not measure or foresee was the indomitable spirit of a downtrodden people. Once unleashed, people power kept gathering momentum at a formidable pace.

So, where to from here? Can Egypt handle its own version of democracy and put to rest the fears that have done the rounds on the news circuit? While the road ahead will be difficult, it is an absolute essential that a transition to democracy takes place and is supported by the international community.

It is not 1979

Egypt will not befall the same fate as Iran. The constant historical comparisons to 1979 Iran are dubious at best.

The Egyptian military establishment, many in the High Council of the Armed Forces who are old enough to still remember, learnt a valuable lesson from the 1979 Iranian Revolution when senior officers in the Shah’s military played a minimal role in the uprising as various Iranian factions battled each other out for control of the revolution. The secular Egyptian military establishment from the early days of the Egyptian uprising intervened, much to the delight of the protesters, and upon the ousting of Mubarak, have taken up the mantle of transition and stability until a civilian government is elected.

Economic considerations often underpin political considerations. The Iranian analogy does not take into account the vast differences between oil exporting economies and service-driven economies. Iran does not depend on the goodwill of the international community as there will always be customers to buy their oil. Egypt does not have this luxury, and maybe for good reason too, as the tourism industry is Egypt’s lifeblood – the country’s image is paramount in order to attract tourists, thus self-sufficiency is not an option to fall back on for the Islamists if they ever thought of implementing ultra-conservative laws. A national income that depends on tourism, Suez Canal revenue, cotton exports and so forth propels Egypt into the world’s inter-connectedness of economic and social networks.

Moreover, it was Facebook and Twitter that played a large part in facilitating the revolution and bringing Egyptians from all walks of life onto Tahrir Square and beyond. An optimistic sign as no political party or ideology could claim credit.

To group the Muslim Brotherhood with other Islamist movements such as Hamas, is to group Europe’s Christian Democrats with the US Evangelical Right. The organisation had denounced violence long ago, and has stuck to it. A diversity of members, especially the younger guard, cooperates with Egypt’s Coptic Christian community and women’s groups.

The only solution to address fears of an Islamist takeover, real or imagined, is to open up the political space to the Brotherhood in a pluralistic process. Mubarak’s regime inflated the fear in order to offer the West himself as the only viable alternative. Democracy will be the great leveller, and a vibrancy of newer political parties will enable Egyptians to choose those with the most promising policies. If the party makes a mess of things, then they are voted out. If recent events are any clue, Egyptians have lost their fear to address corruption and mismanagement head-on.

The Peace Process

A democratic Egypt would put back muscle into the peace process. While no Egyptian, civilian or solider, wants war with Israel – did you hear otherwise from the voices in Tahrir? – they also do not want their government to give the Israelis a carte blanche for hawkish policies in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

The 1979 peace treaty enabled Israel to withdraw its soldiers from Sinai in 1982, with recovery in the defence budget, it consequently made it possible for the Likud party to send the Israeli Defence Forces on a bloody invasion of Lebanon soon after. Moreover, peace with Egypt also enabled the intensification of settlement activity in the West Bank.

Israeli officials found that Arab leaders were easier to negotiate with, as the Arab autocrat was not predisposed to concerns about constituencies or looming elections. As such, Mubarak’s complicity in the Gaza War was the logical outcome.

For far too long, successive Israeli governments exploited Mubarak’s obsession with stability and his reliance on the US. Stability is not mutually exclusive with a more assertive peace-making stance on Egypt’s behalf.

Soft Power

Egyptians are eager to reassert their soft power over the Arab world; a power that was severely undermined by Mubarak over the years, and received a death-knell following Mubarak’s indirect involvement in the Gaza war.

If Egypt is transformed into a democratic state, the implications for the Arab world would be great. When Egypt sneezes, the Arab world catches a cold.

The domino theory of democracy promotion was justifiably discredited under President George W. Bush. Yet there can be some applicability to the democratisation in the Arab world when the locus of activity is viewed as indigenous.

Tunisia sparked off the uprisings in the Arab world, yet Egypt stole the show with its dramatic strength of people power, and has given impetus to other uprisings in the region, with pre-emptive government responses that range from Jordan’s sacking of the cabinet to Kuwait’s offering of free food.

One can hark back to the 1950s and see a raw example of Egypt’s influence on display, with the then Egyptian president Gamal Abdel-Nasser policies arousing Arab citizens against Arab monarchies and Pro-Western regimes, with some successful outcomes. This should not have to be some neo-Pan Arab nationalist resurgence, but an acknowledgement of the fact that Egypt’s image is channelled through the mediums of social, religious, cultural and the popular arts. This can be seen from Arab world developments taking their cues from their counterparts in Egypt down to Lebanese pop singers adopting Egyptian accents.

Just like Brazil’s soft power over Latin America, and India over South Asia, it would be in the international community’s interest for Egypt to be seen as a pluralistic multi-party state to its Arab neighbours who might follow the path of democratisation. Obama’s choice of Cairo for his 2009 speech to the Muslim World was no accident.

It has just begun

While the roadmap to democracy is still being fought over, it would be in the international community’s interests to remove the hesitancy that paralysed Western policy for decades. The Egyptians are not burning any flags. They rose as a nation to take ownership of a revolution, with the discovery of a new self-empowerment that each one of their voices can count.

Peter Hallward, from the Guardian, noted that “Egypt’s mobilisation will remain a revolution of world-historical significance because its actors have repeatedly demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to defy the bounds of political possibility, and to do this on the basis of their own enthusiasm and commitment.”

Only time will tell if the young actors can still defy the bounds of political possibility and achieve a democratic Egypt.

An Egyptian joke from the 1990s went like this: “Impressed with Mubarak winning elections each time with 90 percent of the vote, Bill Clinton asked to borrow his advisors to help with his second term elections. Mubarak’s men went to Washington and supervised the elections. When the votes results came out, the advisors announced: Mubarak had won with 90 percent of the vote.”

Let us hope the next punch line will be a free and transparent electoral system for Egypt.

This article first appeared in Online Opinion