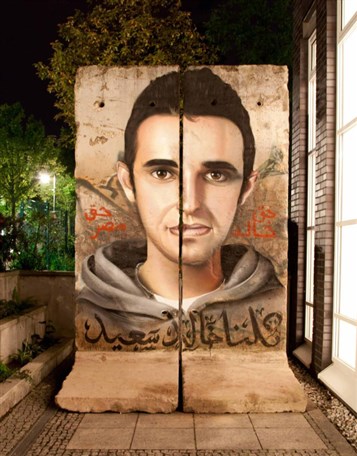

My article on Khaled Saeed at Jadiliyya.

For the Arabic translation: أمثال خالد والثورة: إزالة الأسطورة المحيطة بخالد سعيد

On 6 June 2012, I will join countless others in commemorating the second anniversary of the death of Khaled Saeed, the twenty-eight-year-old Alexandrian who was beaten to death by plain-clothed policemen. The screams of Khaled echoed through Egypt and sparked the rapid countdown to the 2011 Egyptian Revolution.

Khaled was the neighbor down the street to whom I, admittedly, paid little attention. Yet his posthumous transformation from another face in the neighborhood to revolutionary poster child has become a source of both inspiration and concern. Inspiring in that he has given a focus and impetus to Egypt’s revolution, and concern in that his mythologization considerably conceals the real problems that the many “Khaled Saeeds” of Egypt face.

Khaled has been distorted almost beyond recognition. To understand the extent of this, based on interviews from friends, associates, and my familiarity and understanding of the district, I attempt to provide a descriptive account of his life up until that fateful night in June 2010. The facts of his life are contrasted with his mythologization and the polarizing effects of both. His death was not just indicative of the corrupt and brutal police state; Khaled’s life was symptomatic of the widespread despair that continues to plague Egypt’s youth and that manifests in a plethora of symptoms, from drug abuse to the strong desire to emigrate. The reconstruction of Khaled Saeed perpetuates self-defeating myths that, by elevating him into a figure with saint–like qualities, minimizes and simplifies the dynamics of his life that led up to his death.

Khaled’s tragedy was a turning point in my life. I first wrote about Khaled Saeed shortly after his death in an article titled, “Egypt’s Collision Course with History.” On the day Khaled died, I was in Australia reflecting on my late father who had died two years earlier on 6 June 2008, near to where Khaled passed away. When the news of Khaled’s death reached me, it shook my world. It was not just the manner of Khaled’s death that had disturbed me, but the deep reach of President Hosni Mubarak’s repressive police state into a neighborhood where I had grown up and idealized as a beacon of harmony. Up until then, I naively thought that such things happened to other people, in the slums, Islamist strongholds, in prisons, on the news, Alexandria’s rural outskirts, or any “other area.” My area became that “other area.”

Call Me Kaled Wave

Tucked deep away in the catacombs of social media rests the Facebook corpse of one Kaled Wave—the alias of Khaled Saeed. Khaled’s profile photo and Facebook activities would come to a halt like the time-frozen ashes of Pompeii. Ironically, it was the shocking and abrupt interruption of Khaled’s life that would unfreeze Egypt from its morbid state under Mubarak.

The photo speaks volumes of a young man that has been robbed of hope and a future. On his profile, the Alexandria he wishes to live in is not the once-thriving cosmopolitan city of Egypt sixty years ago, but the Alexandria Bay in New York. Instead it was his obsession to emigrate, particularly to the US, after having lived there for a short period of time. The closest form of escapism for Khaled was the Internet. In fact, he lived most his life online, using a pirated Internet connection from the Internet café below his home (not the one he visited on his last night). If his Internet connection went down, he would go down to the Spacenet Internet café (yes, that one) some thirty meters across the street. He would download the latest movies and songs and distribute them to his friends. He had an online relationship with two girls living abroad.

Khaled Saeed means “eternally happy” in Arabic. He often made people happy, but it was questionable whether he himself was ever happy. When he was called up for military conscription, the harshness of army life made him go AWOL. His voluntary return and some family connections landed him with a light military prison sentence of ten months in 2006/2007. Khaled was often center-stage, amusing the inmates with his antics. People rarely knew him by his full name. In his years at school, his childhood [and my close] friend, Wesam Mohamed, states that Khaled was known by, “Khaled Tayara” (“kite”) for attaching razor blades to his kite to threaten its rivals causing all kite-flying enthusiasts to flee the scene upon sighting the winged predator over Alexandria’s beaches. He later took on the nickname “Kaled Wave.” The name, which he went by until his death, was inspired by his older brother, Ahmed Wave—who was often living in the US—and his love for rap music and DJing (Khaled tended to shun Arabic music). It appears on his Myspace account. You knew Khaled was home if the music was pumping out loud from his second floor apartment. Being the resourceful character he was, he would power up his stereo on the beach from lamp pole wires. Finally, he had the less than flattering name of “Abu Sena” in reference to a crooked tooth.

His mother spent a lot of time in Cairo where her married daughter lived, leaving Khaled alone in the apartment – a rarity in a country where most of the young generation live with their families until marriage. Opportunism came knocking at the door.

Having the apartment to himself, Khaled attracted a new set of “friends” that exploited the privacy of his residency for substance abuse and his autophobic nature. They introduced the impressionable Khaled to the world of cannabis. Khaled’s need to “fit in” could at times reach bizarre lengths; on one occasion a friend swiped a medicine bottle from the bathroom cabinet and dared Khaled to drink it all down and he complied.

Tech-savvy, hospitable, youthful, energetic—everyone unanimously agrees that Khaled was always polite and willing to help anyone in need. His close friend Mohammed Mustafa notes that two months before his death, he had little money, and would sometimes forgo meals just to feed his twelve cats. Khaled tells, in his black alter-ego manner, Mustafa, on one occasion: “I’m sick of attracting bitches, I want somebody decent. I just wish to love and be loved by somebody.” That wish was soon to be fulfilled by an entire nation.

Khaled’s Last Sunset

Supporting evidence lends credence to the view that Khaled walked into a trap, and was not the victim of a random police patrol. There is one figure that stands out from Khaled’s circle of friends, Mohamed Radwan, known by his fitting alias Mohamed Hashish. The street views him as the Judas Iscariot that sold out Khaled, and most of Khaled’s close friends are convinced he was on the police’s payroll. One strong piece of evidence for this is that despite Mohamed Hashish’s addiction to hard drugs, the light charges against him do not seem to match the gravity of his narcotics usage. One week prior to Khaled’s death while at Khaled’s apartment, Mohamed Hashish, to sustain his drug habit, stole a hundred dollar US bill from the money that Khaled’s brother had sent him from the US. When Khaled found out, he ran down to complain to his friends of what happened. His friends kept reminding him that Mohamed Hashish was a dubious character (and after Khaled’s death believe him to be a “morshid,” an informant for the police). Khaled was extremely furious at the breach of trust. Mohamed Hashish later called to apologize and Khaled forgave him despite the money not being returned. He would not see Khaled until the night of 6 June.

The police had picked up Mohamed Hashish a few days before Khaled’s death on bodra (a form of heroin) possession charges. Mohamed Hashish is released (meaning charges were most likely later dropped) and according to Mohamed Mustafa and most of Khaled’s friends, this was allegedly done in exchange that Hashish would participate in a police setup designed to arrest Khaled.

The popular view is that Khaled had a video of police officers sharing the spoils of drugs, and therefore the police wanted to catch Khaled. I am highly skeptical of the whole video claim, which does not square up with Khaled’s persona or activities and a number of Khaled’s friends are divided over this matter.1 It comes across to me as a saving grace to shift attention from Khaled’s drug use to something more heroic. Wesam is in the camp of doubters: “I don’t buy the video, even when you watch the video, it’s open to different interpretations.” It is not that the police were concerned about Khaled’s welfare [that they were not], but the opportunity to catch someone in possession of drugs could mean anything from a promotion and fulfilling a quota, to holding something against Khaled in future in exchange for bribery or police cooperation. Mustafa notes the irony: “[Mohamed] Hashish is known to do the heroin and gets released, but it’s Khaled who gets killed for bango (a form of cannabis).”

Compelling circumstantial confirmations reinforce the lack of randomness and high likely involvement of Mohamed Hashish in that fateful ordeal. Islam Al-Messery, the owner of the Internet café just below Khaled’s building, notes that he has never seen before those two police officers on their street. Mustafa adds, “They were sighted in the late afternoon doing one big walking lap as if something was being cooked up.”

Wesam also points out; “Khaled was under-dressed in a way that indicated he was not leaving his street, just going to pick something up” (Khaled was wearing white long shorts and a black shirt the night of his death).

Mohamed Hashish has a notorious reputation that goes back to his conscription years. One source stated several years ago, Hashish went around the local area promising job offers to work at Alexandria’s esteemed petroleum company. The applicant had to pay 150 Egyptian pounds for the offer. Nothing came of it, and there was anger at Hashish as a result. In light of Mohamed Hashish’s dubious background and sycophantic reputation, he may not have been coerced but rather was opportunistic given his fixation with building connections. Yet Mohamed Hashish’s extreme despairing behavior on the night of Khaled’s death also indicates he was not expecting Khaled to die.

On the fateful humid summer Sunday night, Mohamed Hashish contacted Khaled and informed him that a drug seller would meet with them on the corner of their street facing the coast. After the sun had set over the Mediterranean just after 7 PM, Khaled walked with Hashish and bought his bango (There is a black out straight after this of two hours that I’m still investigating). Mustafa reports according to second-hand testimony that Khaled suggested that they both go to his place. Hashish replied “Just come with me to the cyber [Spacenet Café] as I have to see something.” They continued walking towards Spacenet Café. As Hashish was speaking on his mobile through an earpiece (most likely to a friend), he is sighted doing a hand wave and slowly walked away from Khaled (but close enough for a conversational distance). A nearby mobile phone store run by a Salafi notes “It was way after Isha (the Muslim night prayer, around 8.30 PM) when all the commotion began.” It was after 10 PM.

Two police officers follow Khaled into the Internet café as Mohamed Hashish parts. One reliable anonymous source states: “At this point, Hashish walks (some say ran) on foot towards the Sidi Gaber police station and drives the police van back to the scene himself.” This claim transforms Mohamed Hashish from snitch to a barefaced accomplice. It would be incredulous if it were not for sightings of Mohamed Hashish with twomokhbereen (“detectives”) for his protection in the period following Khaled’s death. Back to the Spacenet Café scene, one police officer asks Khaled what he has on him and then inserts his hand into Khaled’s pocket. Khaled shoved one of the officers back making some references to the law and his dignity. The spited officers grabbed Khaled from his long hair and the beating began, first in the Internet café and continued into the doorway of the adjacent building. The details are on record. Khaled screamed, “I’m dying”, the police replied “I’m not leaving you until you are dead” (possibly not meant literally). The chilling aspect of the entire beating is that the gathered crowds did not get involved. One friend remarked: “We just did not think he would die, and this was the police we are talking about, who could stop them?” It is hard to believe it was only two years ago that Egyptians were that terrified of the police, even when they were brutalizing a young citizen.

[The entrance of the Spacenet internet café where the police confronted Khaled and began beating

him (You can see the stairs and marble shelf where Khaled’s head was hit). Photo by Amro Ali]

After the beating, the two police officers board the police van with Khaled’s dying body and drive back. Barely ten minutes later, the van returns and dumps Khaled’s dead body out in front of the building where he was beaten. Sitting in the police van past midnight, Hashish was in tears repeating, “I told Khaled not to carry drugs” to Wesam, Hashish disappeared from the social scene for many months fearing retribution (Although he had protection). In court he gave a watered down version that pinned the blame more on Khaled than the police. Mustafa remarked, “What is he fearing? We’ve just had a revolution!” Until this day, friends report that Mohamed Hashish has not been forthcoming with all the details of Khaled’s exact movements and conversations in the lead-up to his death.

[Entrance of the building adjacent to the internet café and the site where

Khaled was dragged and beaten to death. Photo by Amro Ali]

The question is still an open one as to whether Khaled swallowed the bango packet or if it was forcibly shoved down by the police. Interestingly, Wesam states “I came when they were lifting Khaled’s body into the ambulance, and his face looked morbid but it did not look like the horrific disfigured cut-up face you see in the photo, that photo could only have been taken after an autopsy.” In any case, the police behaviour and actions created the conditions that facilitated Khaled’s death. Khaled never made it past midnight, Egyptian history was altered, and the Khaled Saeed myth was born.

[Protest following Khaled Saeed’s death. Photo Tarek Fawzy/AP]

[Protest following Khaled Saeed’s death. Photo Tarek Fawzy/AP]

The Road to Mythologization

The name Khaled Saeed quickly grew to Rosa Parks’ proportions. His image from his photograph has become the enduring hallmark in Egypt’s revolutionary movement. Cleopatra square, adjacent to the crime scene, has become the “pilgrimage” site and way station that protesters march through and chant variations of “We are all Khaled Saeed.” As if by design, Cleopatra Square is positioned at the spearhead to the Northern Military Command headquarters in Alexandria where marching protesters end up creating a backlog.

The Poet David Lawrence noted that a “myth is an attempt to narrate a whole human experience, of which the purpose is too deep, going too deep in the blood and soul, for mental explanation or description.” Yet an attempt needs to be made if we are to understand the meteoric rise of Khaled Saeed and the national discourse he has shaped, and in turn has shaped how Egyptians perceive Khaled Saeed.

[Aftermath of Khaled Saeed’s death in Cleopatra Hamamat. Image from Almasry Alyoum]

[Aftermath of Khaled Saeed’s death in Cleopatra Hamamat. Image from Almasry Alyoum]

Khaled’s myth is not surprising given that it was born out of an area that bears witness to the sparring forces of myth and history. Khaled lived and died on Medhat Seif El Yazal Khalifa Street in the middleclass suburb ofCleopatra Hamamat (“Cleopatra’s Baths”) – a possible namesake legacy of Queen Zenobia’s conquest of Egypt in 270 CE. Zenobia established the cult of Cleopatra and styled herself as Cleopatra the New.2 The suburb last made headlines in World War II, when, according to local legend, the ghost of Sidi Gaber (a Moroccan Sufi who settled in Alexandria several centuries ago) saw the Axis warplanes approach as they were about to bomb the British military installations in the Sidi Gaber suburb. As to protect his adjacent mosque, which bears his name, waved the planes away and hence, the story goes, all the bombs fell on nearby Cleopatra Hamamat in the first week of the campaign.3 That was June 1940. Fast-forward seventy years to June 2010 and another ghost was to be offered up and that would eventually wave Mubarak away.

The case of Khaled became infamous, it is argued, because his death took place in brazen public and the grainy photo of his mangled face in the morgue haunted the nation. There is little dispute in that, but it does not take into account the factors that made Khaled a unique case in a country where victims of police brutality are not uncommon and have been caught on film in the past, though not with the same degree of gruesomeness.

[The ghost of Khaled Saeed seizing Mubarak during the 25 January revolution. Cartoon by Carlos Latuff]

Arguably, one of the factors that aided Khaled’s ascendency to the pinnacle of celebrity martyrdom is that he came from a middleclass background. This is critical as society is often more reflexive to individuals who enjoy such a profile than they would be to those of lower socio-economic or impoverished backgrounds. Another factor is that Khaled had no known connection to religious or political movements, and, therefore the absence of any obvious ideological bent in his background enabled many to claim ownership of Khaled as “their” everyday Egyptian. The fact that Khaled died in Alexandria tilted the scales. Reinforced by the popular arts, Egyptians are culturally predisposed to associate the coastal city with romance, escapism and various positive connotations. Had Khaled died in Sohag or Aswan, he might have gone unnoticed. Alexandria is Egypt’s epicenter of vanguard gravity, especially in relation to the country’s socio-political dynamics.

The street politics of Cairo matter most here. The absence of notable fact-checking human rights organizations in Alexandria, unlike Cairo, permitted a distorted view to come out. This was further aggravated due to Cairo-based activist circles’ reporting and “gratuitous” usage of embellished circumstances surrounding Khaled’s death. The fact that his tragic death crossed over into Cairo’s hub of movers and shakers further entrenched his national legitimacy and hastened his mythologization.4

Khaled also provided the missing link to the social media savvy generation – he was martyred at an Internet café while allegedly about to upload a video to YouTube of crooked cops sharing the spoils of drug money. However, irrespective of corroboration on this matter, the initial YouTube video claim fomented a rapid cognition to which people reacted intensely. One wonders if Tunisians would have reacted as vehemently if Mohammed Bouazazi were labeled a fellah fruit vendor rather than an unemployed middle class university graduate, as erroneously reported in initial accounts. The horrific image of Khaled’s mangled face went viral through the social media and the creation of the “We are all Khaled Saeed” Facebook page by Abdelrahman Mansour and Google executive Wael Ghonim transformed and sustained Khaled as a focal point for the nation to rally behind. Khaled became the human face of Egypt’s tragedy, but also its digital youth.

It is tempting to ask as to why did Cleopatra Hamamat’s residents not speak out to verify the character and fate of Khaled from the start? It is a case of the Al Capone syndrome. The Chicago gangster who despite running a vast criminal enterprise and murdering numerous rivals, is dethroned and imprisoned on mere tax evasion. For all intents and purposes, Khaled Saeed’s tragedy was not the worst the Mubarak regime had done, but once the incident exposed an Achilles Heel in the regime, Khaled then became the answer to redress all the lives taken away and injustices suffered in the past. It was more pertinent to stay quite if the myth served the purpose of the Mubarak regime unraveling itself. In any case, the national outrage was deafening that it was difficult to put any contrary view. One example was straight after the Egyptian revolution when I made one bare reference to drugs and Khaled Saeed on an Australian program; I received irritated calls the next day from Egyptian diplomats and other community figures.

This is not to discount the political context of the Mubarak era that had reached the end of its tether. The Egyptian public’s frenzied reaction at the return of Nobel Peace Laureate Mohammed ElBaradei in February 2010 more than hinted at the unquenched thirst for a “Messiah.” The stage was set, the script was written, and it now awaited the “appropriate” actors to show up and play out their assigned roles. Khaled was to be the chief martyr.

[Painting of Khaled Saeed in San Stefano, Alexandria, now painted over. Photo by Amro Ali]

[Painting of Khaled Saeed in San Stefano, Alexandria, now painted over. Photo by Amro Ali]

So the question arises, what is problematic about Khaled’s mythologization? The very factors that play a part in constructing the Khaled Saeed we know today are the same factors that mask Egypt’s dysfunctional social system. The concentration of human rights advocacy work in Cairo at the expense of the rest of Egypt is an example. When a human rights worker in Cairo spoke to me in a self-congratulatory tone about what they did in Khaled’s case (as if to say Alexandria does not need its own representation), I responded that human rights depends on local knowledge of a city, extensive networks of contacts, lawyers, and importantly, for the police to know that they are being watched. This may explain why policing behavior is often much more brutal outside Cairo.

Other questions need to be raised from the subtext of the Khaled Saeed construct: What about the rights of those of lower socio-economic backgrounds? Does it matter that a rural youth may not have had access to the Internet? Would a dark-skinned Nubian victim garner as much attention? Can the term ‘martyr’ be applied to a Copt? To what extent would it have been her “fault” if it were a woman in Khaled’s exact same situation? Is there even a concept of Bedouin youth in Sinai? When you add it all up, there are many “Khaled Saeeds” out there on standby who we may never, and we don’t, hear about. Instead of utilizing Khaled Saeed as a signpost for the country’s current disparity and looming socio-economic problems, we use him as the template of what a good martyr should be and look like.

[Balcony of Khaled’s apartment, with his name written in Arabic. Photo by Amro Ali]

The Polarizing Saeed Effect

One of the spin-off effects of the Khaled myth is that it blames the victim, both implicitly and explicitly. Khaled Saeed’s myth is inescapable almost everywhere in Egypt except, not surprisingly, in our neighborhood where there is a degree of backlash with accompanied rolling eyes when the name Khaled Saeed is brought up – not helped by the world’s media inundation. I end up having to bite my tongue, if not argue, with my barber or neighbors following statements like: “Khaled used to harass girls” or “Khaled was not a good boy, he did drugs.” The implication of their remarks was that Khaled somehow deserved what came to him. This is not to mention my surprise at a comment by a mutual friend of Khaled’s straight after his death: “Khaled should not have run from the police!” (in any case, he did not). So Khaled is to blame for the police killing him or at the very least, the police behavior and conditions that led to his death?

Khaled Saeed (posthumously) gets off lucky, given that the social illness of victim blaming is all-pervasive. The Tahrir girl is a case in point – the young physician activist whose brutal beating at the hands of the military exposed her flesh and blue bra to the rest of the world last December. Well not many were blaming the military, according to popular opinion on the Egyptian street she “provoked them,” “was not wearing the hijab properly,” “the military does not wear running shoes,” “the image is Photoshop-ed” and insert your ‘denial is a river in Egypt’ reasoning here.

Decades of Emergency Law and Mubarak’s thug rule have torpedoed notions of arrest warrants, due process, and rule of law. This is why a Mubarak-era figure like Ahmed Shafiq with a questionable record can have the audacity to run for president and garner enough votes to make it to the run-offs. The promise of stability, it seems, is mutually exclusive with the rule of law.

The revolution’s unchecked adulators of Khaled Saeed indirectly contribute to blaming the victim syndrome – the very social injustice they seek to fight. In absolving Khaled of drug abuse and any other social-perceived misconduct leaves open the interpretation that someone who does otherwise is fair game to a police lynching. Raising Khaled to cosmic levels of heroism diminishes the real challenges that Khaled, and hence Egyptian youth, face daily. Khaled was not from another planet; he was the product of contemporary Egyptian society and its troubled young generation. Subjecting Khaled to sanitization, an airbrushed passport photo, an activist profile makeover, and parroting the questionable possession of an anti-police video does no justice to real day-to-day problems faced by youth and ends up censoring the questions of what pushes them to drugs, depression, religious extremism and so forth. What others and myself say will not change much the popular view of Khaled – a myth is more powerful than history.

[Khaled Saeed’s passport which includes the widely circulated

personal photo. Source: “We Are All Khaled Saeed” Facebook page]

Finally, mythologization has underpinned the politicization of Khaled Saeed. One’s view of Khaled depends on one’s politics. On the one extreme, the 6 April Youth Movement has put Khaled on a pedestal – the wholesome and unadulterated Khaled. On the other, the Felul, Mubarak’s regime remnants, have pushed the “drug user Khaled” line (or ‘Marijuana Martyr’ as they once tactlessly called him) not because of a newfound respect for accuracy, but to vindicate the Mubarak regime. The Egyptian media circuit and nationalist commentators weighed in by inflating Khaled in order to eclipse the significance of Bouazizi and his act of self-immolation – it was an unforgivable crime that “lightweight” Tunisia should upstage the “mother of the world” by striking a blow to Egypt’s ego when it kicked off the Arab uprisings. The list of Khaled lovers and haters for their ends are, to say, endless. Not to mention a relative of Khaled’s whose unsuccessful bid for parliamentary elections last November had a less than subtle tagline: “Uncle of Khaled Saeed.”

The Road Ahead

Khaled’s tragedy is Egypt’s tragedy. We should not commemorate him because he was either a saint or sinner, but simply because he was a human being who was robbed of his rights and dignity once he breathed his last. We stand not only in commemoration of Khaled Saeed but also the countless nameless and faceless lives taken away before and since. Khaled’s mother, Layla Marzouk, is a remarkable woman who works tirelessly to bring attention to the mothers who have lost their children to the regime. Such a fraternity does not need any more heartbroken and distraught members.

[Khaled Saeed’s grave, 27 January 1982 — 6 June 2010. Source: “We Are All Khaled Saeed” Facebook page]

[Khaled Saeed’s grave, 27 January 1982 — 6 June 2010. Source: “We Are All Khaled Saeed” Facebook page]

Khaled had started to turn his life around for the better in his final months. Only for all that to be cut short—very much the feeling many Egyptians have about the revolution. The theatrics of the recent Mubarak verdict that resulted in his light sentencing, along with former Interior Minister Habib Al-Adly, and the acquittal of Mubarak’s sons and the security henchmen, has once again reignited the revolutionary fervour across Egypt. As counter-revolutionaries and the felul, with the blessing of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), dig their heels in, Egypt’s revolutionary forces are overcome with a premonition they are going to experience more anguish as they seek to write Egypt’s Magna Carta with their blood, sweat and tears.

Khaled Saeed is a myth, but a necessary one. The extended Egyptian revolution is also a war of ideas whose story will prevail. The fate of Khaled Saeed is a reminder and an encapsulation of why Egypt rose up and keeps pushing the revolution painstakingly forward. Khaled Saeed enabled Egyptians to personalize and humanize complex issues that could otherwise have drifted into murky abstractions.

[youtube]https://youtu.be/neTpwMSvHUk[/youtube]

[Protest in Cleopatra Square chanting Khaled Saeed’s name on 30 May 2011. Video by Amro Ali]

[youtube]https://youtu.be/FTWWxyEStwg[/youtube]

[Aerial view of protest marching through Cleopatra Square

shouting Khaled Saeed’s name on 13 April 2012. Video by Amro Ali]

As Egyptians commemorate Khaled Saeed this year and in years to come, they also need to make peace with Kaled Wave so as to tune in to the war cry of a swindled generation whose political exclusion for so long has left them with the dilemma of drug abuse or religious extremism—the social equivalent of the current Ahmed Shafiq-Mohamed Morsy dilemma. A third way out is still pressing. Egypt does not need more Khaled Saeeds, it needs inclusive progress that can bear a torch to the youth and show them some semblance of what it is to be “eternally happy.”

[The youth have unofficially renamed the street where Khaled lived and died after him. Image: Amro Ali]

[The youth have unofficially renamed the street where Khaled lived and died after him. Image: Amro Ali]

—————————————-

[1] Wael Ghonim dismisses the video claim in his book Revolution 2.0.

[2] Okasha El-Daly, Egyptology: The Missing Millennium: Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings (London, UCL Press, 2005) 137.

[3] Interview with Magdy Hewedy, aging resident in Cleopatra Hamamat.

[4] Amro Ali, “E-gypt: The Convergence of Politics, Demographics, and a Wired Society,” Transcript of presentation given at Columbia University (29 September 2011).