Published in Mada Masr

For the Arabic translation, see انقذوا الأسكندرية.. وأفرجوا عن شريف فرج

Sherif Farag is “one of the greatest persons you can meet” tweeted prominent Alexandrian activist Mahienour al-Masry. Sherif is a Master’s student and assistant lecturer at Alexandria University’s Faculty of Fine Arts. He is also one of the most underrated activists you will ever meet in the coastal city. Following his vocal opposition to the protest law, his life took a turn for the worse when the infamous late-night police raid occurred.

At 2.30 am on Sunday, November 24, a large security force of over 20 heavily armed men entered Sherif’s family apartment in Sidi Bishr, Alexandria. Masked security forces occupied the staircase of the building. Security convoys blocked the street. And all this deployment was to arrest a rising academic and advocate for the rights of teaching assistants, for architectural standards and heritage preservation.

The travesty did not end there, however. Taken to the security directorate in Smouha, in the presence of his lawyers, the charges leveled at Sherif were “joining a banned group” — presumably the Muslim Brotherhood, which Sherif is not a member of, nor affiliated with in any way.

Realizing that such a charge could prove difficult to stick on Sherif, still more trumped-up charges were thrown at him. At 10 pm that same night he was charged with campaigning to promote chaos, mobilizing crowds, and using violence.

The next day he was charged with planning and killing peaceful demonstrators, breaking cars and — just to make sure that the ludicrousness of the whole case was sealed — robbing a bank.

Since November 28, Sherif has been in Hadara Prison pending investigations. On December 8 his incarceration was renewed for another 15 days, despite the fact that there is no evidence or witnesses to incriminate him. Throughout this period, there have been daily protests and petitions demanding his release.

Sherif’s academic activism was in many ways a success story of the January 25 revolution. As his friend Ahmed Hassan noted: “Sherif’s positive attitude, motivation and inspirational effect on people guaranteed him a fixed place in the emerging academic and cultural groups in Alexandria. His campaigning for the rights of teaching assistants was integral to the collective effort that helped champion the cause of teaching assistants throughout Egyptian universities. This was also followed by his rise to sit on the advisory committee of the Ministry of Higher Education in order to deliver our demands to the decision makers.”

But it was Sherif’s presence on the street that made him familiar to the public, and Alexandrians in particular. He led peaceful demonstrations to protest against Alexandria’s real-estate mafia and its destruction of the city’s heritage. He spoke against the dangerous proliferation of tens of thousands of buildings that violate basic safety standards and consequently lead to the frequent tragedy of the city’s collapsing buildings.

Sherif was part of a growing swathe of Alexandrian activists who increasingly shared the view that Cairo’s centralized decision-making was the main source of Alexandria’s problems — a situation that must be rectified.

It was tacitly understood among Alexandria’s civil society scene that heritage and building issues were critical concerns shared by all groups. Facebook groups and pages such as Alexandria Scholars, Alex Agenda and Radio Tram united behind the Save Alexandria initiative. This initiative, co-founded by Sherif, was primarily aimed at the preservation of the city’s architectural heritage. But it has become a political platform for activism in Alexandria.

The initiative presents itself as a pressure group that works at ensuring Alexandrians’ “right to their city” — often through organizing protests. “Save Alexandria’s” Facebook page has been used to publicize protests and mobilize people to take part. Naturally, the prominence of this initiative, along with Sherif’s university activism, put him on state security’s radar.

Sherif took a sophisticated and multi-faceted approach to his activism that ranged from protest vigils, media interviews, to sitting down with officials to try to work out a solution to the city’s problems.

When Sherif spoke of the city’s problems, it was articulated with such eloquence and succinctness that it was bound to disturb those in power. I recall one scene last year in which Sherif, myself, and his friend Ahmed were invited to speak with the governor at a roundtable meeting at the engineers’ club overlooking the Mediterranean. We were the youngest ones in a room full of sycophantic public officials and aging, self-obsessed “call-me-doctor” academics. They seemed to have trouble accepting our presence at such a high profile meeting. Nevertheless, Sherif spoke loudly and eloquently of the city and the people’s problems.

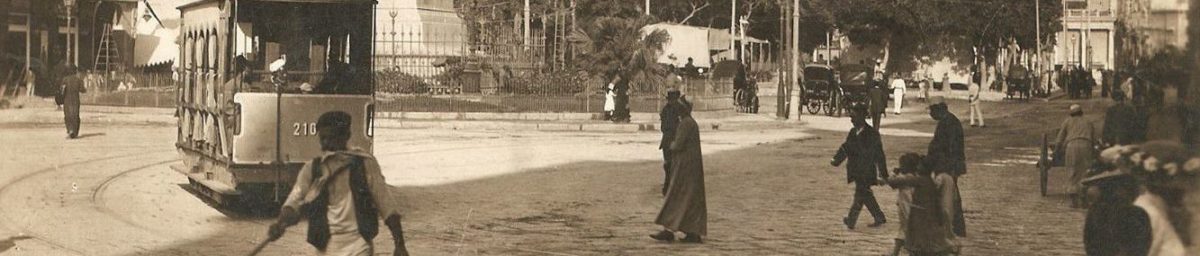

“You are standing on Fouad Street, one of the oldest [continually used] streets in history,” Sheirf told me once during a protest. Passionate about saving Alexandria’s heritage, he laments today’s building culture, and how nobody teaches or learns architecture properly: “Every building that rises looks like the other,” he told me.

Noha Mansour, who got engaged to Sherif in August, told me, “Sherif is the type of person who values freedom of speech and action deeply. He never feels ashamed to speak his mind and express his opinions. I feel it was his outspoken opposition to the recent protest law that finally made the authorities arrest him.”

Sherif is due to submit his Master’s thesis this month. He sent this note from prison to be added to the opening page of his dissertation:

This letter was written from my cell, where injustice and aggression abounds, I write these points in the hope that higher education in Egypt will someday be in a better position — though it never will be as long as universities are not liberated from the security [regime’s] iron fist and power. I have worked over two years and a half in an attempt to improve the situation of Egyptian universities after the great 25 January 2011 Revolution. I have played a part in contributing to the increase of salaries of faculty members and have been at the forefront as a member of the Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Higher Education to focus on reforming how universities are regulated. Yet people so retarded [in the security sector] have continued to hamper our progress [in the cause of higher education]. If my imprisonment is a result of my suffering to better education, then no fault can be found with that. God Alone is sufficient for me, as He is the best disposer of affairs for me.

The Researcher

Sherif, locked up in a prison cell, has come to represent the “two Egypts” in conflict. One is bland, unimaginative, archaic, and brutal. And then there is Sherif Farag, along with many others now under arrest, who epitomize a passion, fearlessness, and hope to build a better tomorrow.

Imprisoning Sherif Farag is akin to imprisoning the dream of a better Egypt. His freedom is a necessity.