[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9YZ8sqJI6qY[/youtube]

(If above video not working, go directly to link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9YZ8sqJI6qY)

On a windy evening, 27 April, a momentous event occurred that received little international headline but was significant to Egypt’s future, and, by extension, the Arab world. An unprecedented debate took place between the Muslim Brotherhood, led by Sobhi Saleh, and the secular liberals, led by Amr Hamzawy.

The event was scheduled to be held in the famous Library of Alexandria. But a last minute unexplained decision shifted the event across the street to the College of Law, Alexandria University.

The venue packed over ten thousand into the theatre, with students, activists, and the general public, cramped into seats, spread on the floor, dangling off windows. Doors were forcibly shut to stop the public from entering an already over-crowed venue.

A sharp suited, clean shaven, Muslim Brotherhood figure, Sobhi Saleh, entered to a loud round of applause, but it was Amr Hamzawy who was greeted with a thunderous applause, which was a foretaste to where the young generation was leaning towards.

Hamzawy walked in the room with an aura of coolness, youthfulness, and representing a future where the aging Saleh had the baggage of Islamist history that he needed to shed.

Hovering above the debate stage was a huge mural of three law students who had been killed by Mubarak’s regime during the revolution. Following prayers and a minute’s silence, it was clear the martyrs sacrifices were not going to go down in vain, as Egyptians experienced a taste of their first democratic style debate about Egypt’s future: without fear, the threat of censorship, or government minders in their midst.

Saleh was the first speaker, eloquently outspoken, but predictable: “In the West, they say Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God. But it’s said in the Holy Book that God is the Lord of the heavens and the earth.” The separation of faith and state is a matter that the upper echelons of the Brotherhood are wrestling with. Sobhi delivered an overall powerful and compelling speech.

Come Hamzawy’s turn, it was nothing short of impressive. He had to walk a fine line, as it was a combustible audience while he unrolled the viability of a liberal democratic model. At one point, an old man behind me stood up and denounced Hamzawy by shouting a series of Islamic creeds. Interestingly, the protester followed it up with, “The Muslim and Christian are united”. In other words, he is opposed more to the idea of religion separated from politics, than just Islam’s role itself.

Despite his numerous supporters, it could not have been easy for Hamzawy. At times it looked like Hamzawy was forgetting the audience he was talking to; an intelligent audience it was but still wishing that their traditions and values are incorporated into a democratic form of governance. The democracy discourse needed to be tailored to the Egyptians. Sobhi did himself no favours by not answering the question on the role of women in politics in a future Egypt. Due to favourable circumstances of history, Hamzawy utilised Turkey and Indonesia as a model that Egypt can adopt. This muted some of the Brotherhood supporters.

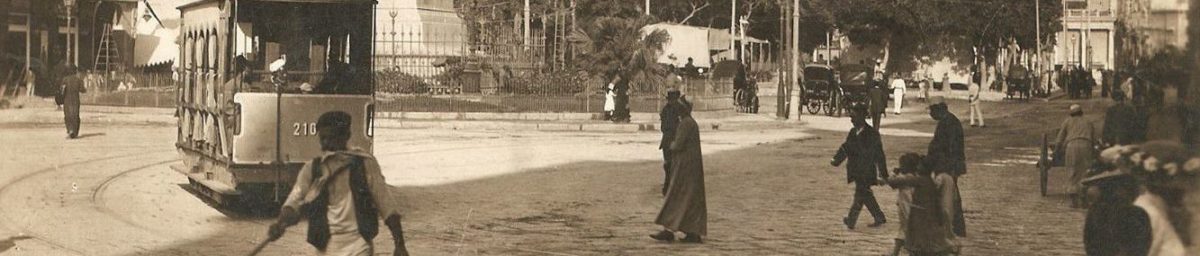

What intrigued me was that Sobhi towards the end in his final argument, moved on from religious arguments to nationalist ones. He raised Egypt’s ancient Pharaonic glory and its central role in world history and trade, discussing the challenges that need to be addressed right down to its inability to bring its universities into the top 500 rankings. The Brotherhood had all of a sudden gone Nasserist and Pan-Arabist. These points brought out an exuberant reaction from the audience, with collective shouts of “You are the Egyptian, you, you are the Egyptian, you!”. Overall, the intense patriotism in the air broke the barometer. The year had winded back to 1956.

It would seem the Muslim Brotherhood are more pragmatic than they are given credit for. They have matured to a considerable degree, and now have disavowed their aim for a theocratic state, but rather a civil one.

Just as the Brotherhood are pragmatic, so are the potential voters. After the event, I spoke to several students and where they stood. Describing themselves as quite religious, most students said they would not vote for the Brotherhood in an election, not so much because of fear of an Iranian style theocracy (which they doubt could ever happen in Egypt). But that the Brotherhood, like all politicians, have expressed a high degree of self-interest in the constituencies they do dominate. Earlier, a bearded Muslim stated that he acknowledges the great work the Brotherhood has done in terms of social welfare services for the poor, and the respectable individuals within the organisaiton, but he cannot imagine them running foreign policy and economic development. He favoured Arab League chief Amr Moussa.

The uncertainty grows day by day as Egyptians are less willing to give a straight answer for their favourite candidate in a climate of increased confused political activity, de-Mubarakisation, and the immediate need to address their economic concerns.

For democracy to work, there will need to be a factoring by pro-democracy activists of Egypt’s deep rooted conservative nature. Egyptian Muslims, in particular, vis-à-vis the revolution were declaring to the world that Islam and modernity are not incompatible.

An Arab League study showed that 72 percent of Egyptians believe that religion should have a say in politics, as opposed to Syria’s 42 percent. The average for the Arab League countries is way below the Egyptian benchmark. The political implicatios can be read in two ways. While at first glance it could mean that the ground is fertile for Islamist based parties to thrive, it could also mean, and most likely, that voters feel Egypt is secure enough in its religiosity and the focus should be on freedom, bread, and dignity: the rally cry of the uprising.

While world attention is focussed on Osama Bin Laden’s corpse lying at the bottom of the ocean. It would be prudent to move from the past and look to the future that is being shaped on the streets, halls and campuses of the Arab world’s largest and geostrategic heavyweight.